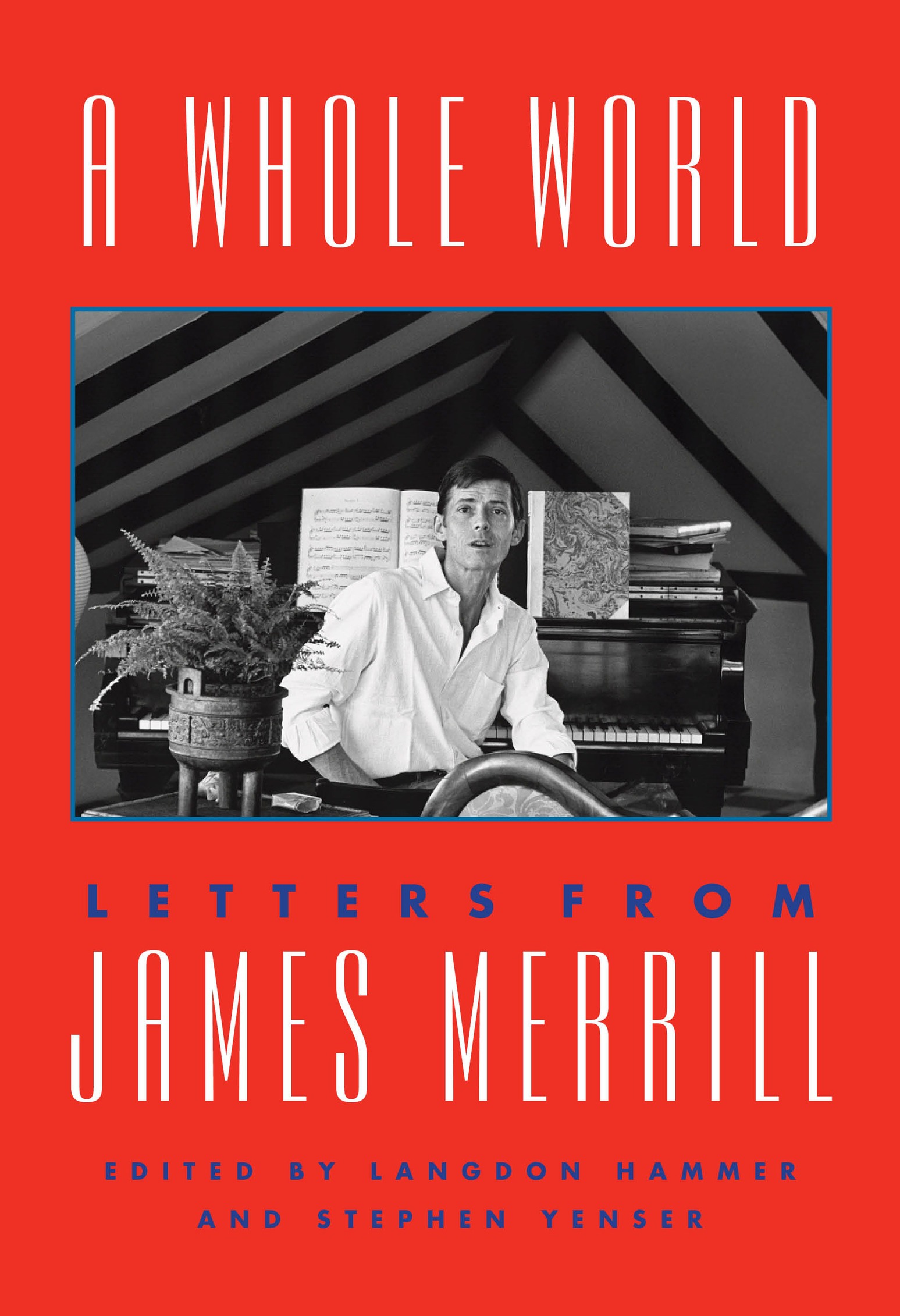

James Ingram Merrill - A whole world letters from James Merrill

Here you can read online James Ingram Merrill - A whole world letters from James Merrill full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:A whole world letters from James Merrill

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A whole world letters from James Merrill: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "A whole world letters from James Merrill" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

A whole world letters from James Merrill — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "A whole world letters from James Merrill" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

The Black Swan

First Poems

The Country of a Thousand Years of Peace

Water Street

Nights and Days

The Fire Screen

Braving the Elements

The Yellow Pages

Divine Comedies

Mirabell: Books of Number

Scripts for the Pageant

The Changing Light at Sandover

From the First Nine: Poems 19461976

Late Settings

Selected Poems 19461985

A Scattering of Salts

The (Diblos) Notebook

The Seraglio

The Immortal Husband

The Bait

Recitative

A Different Person

Collected Poems

Collected Prose

Collected Novels and Plays

The Changing Light at Sandover

this is a borzoi book published by alfred a. knopf

Compilation copyright 2021 by Langdon Hammer and Stephen Yenser

Merrill Letters copyright The Literary Estate of James Merrill at Washington University

Introduction copyright 2021 by Stephen Yenser

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

Names: Merrill, James, 19261995, author. | Hammer, Langdon, [date] editor. | Yenser, Stephen, editor.

Title: A whole world : letters from James Merrill / edited by Langdon Hammer and Stephen Yenser.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2021.

Identifiers: lccn 2020026454 (print) | lccn 2020026455 (ebook) | isbn 9781101875506 (hardcover) | isbn 9781101875513 (ebook)

Subjects: lcsh : Merrill, James, 19261995Correspondence. | Poets, American20th centuryCorrespondence.

Classification: lcc ps 3525. e 6645 z 48 2021 (print) | lcc ps 3525. e 6645 (ebook) | ddc 811/.54 [ b ]dc23

lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020026454

lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020026455

Ebook ISBN9781101875513

Cover photograph: James Merrill by Rollie McKenna, 1969 Rosalie Thorne McKenna Foundation, courtesy Center for Creative Photography. Print: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Rollie McKenna.

Cover design by Chip Kidd

ep_prh_5.6.1_c0_r0

In memory of J. D. McClatchy

One day, of course, you may open one of these envelopes, and I myself will fall out, tiny and dry, like the Japanese flowers, for you to revive in a bowl of water, or clear soup. Be sure you shake each envelope carefully, or you may lock me away in a drawer.

So James Merrill wrote at age twenty-four to his lover. He had almost forty-five years remaining in which to slip his speculations, advice, and metaphors into envelopes posted almost daily and from all parts of the world. He wrote impressively often to many people he knew in strikingly different contexts: his family; friends from his youth (he never let relationships lapse); his lovers; new acquaintances (he was ever alert to cultivating them, especially among younger generations, partly because he was wary of losing touch with the times); and fellow writers and scholars whose views affected his poems more or less directly.

Merrill might turn out to be the last great American letter writer. His adored friend Elizabeth Bishop once proposed a seminar at Harvard on what she called Letters!Just lettersas an art form or somethingan art form, she opined, that was the dying form of communication. That was in 1971, a couple of decades before email became ubiquitous, not to mention the subsequent expansion of social media. Unlike W. H. Auden, a more distant friend and influence, who asked upon his death that his correspondents burn his letters to them, Merrill wanted his to be preserved. He kept drafts and carbons, especially when he was younger, and his provident friends saved their copies, just as he usually saved their letters and cards to himthousands of pieces of his correspondence are in the Special Collections of Olin Library at Washington University, and a substantial number are at the Beinecke Library at Yale, in addition to those at a variety of other institutionsin part because he wanted the record of his life to be as complete as possible. One early letter here to his mother records his dismay when she destroyed correspondence from some of his closest friends. His reaction, as he describes it in his memoir, A Different Person, verged on the corporeal: her crippling blow left him in shock. The loss of some of the letters not only had dealt an incalculable loss to posterity but also had left him with little evidence of having been loved by anyone, except her.

Readers of his memoir have had a glimpse of the color and density of the life he wished to record and to shape. The books 271 packed pages establish as a point dappui the period of two and a half years that he spent abroad in 195052. Subsequently a different person in two senses of that word, if he hadnt been in the first place, Merrill was an inveterate dualist. His once troublesome need to dramatize the ambivalence I live with, he says to a correspondent, soon became the very stuff of my art. Temperamentally inclined to contraries, he believed, he told an interviewer, that the ability to see both ways at once isnt merely an idiosyncrasy but corresponds to how the world needs to be seen: cheerful and awful, opaque and transparent. His favorite literary devices, from pun to paradox, reflected that conviction, and so did his geographical affinities. When he left for Europe, he wanted to explore the old world new to him and yetby means of his many lettersto strengthen his ties at home. His opposing penchants for movement and for permanence generate the paradox latent in the closely crafted opening sentence of A Different Person: Meaning to stay as long as possible, I sailed for Europe.

Years later, in The Book of Ephraim, he quoted Peter Quennells biography Alexander Pope, and, meaning to stay as long as possible himself, he would have known that Auden approved of Quennells report of Popes faith that his letters were bound to interest posterity, that he was establishing a link between himself and his unborn readers, and that when he took up his pen, he assumed the vigilant attitude of the creative artist. Just such vigilance pervaded all that Merrill did. If it led him to admit in his journal that disparagement of his poetrys aversion to the social effects of politics and money could depress him, it also gave him perspective on the pulsing N*O*W and shored up his trust in those unborn readers. The same faith encouraged him to shrug off criticism that his poems could be exacting and required patience to understand, let alone appreciate.

His predilection for doubling up contributed to the works difficulty yet also, surprisingly, to its broader appeal. Beginning in the 1950s, even as he was making a life on both sides of the Atlantic, he was creating connections between this world and the realm beyond. He and his partner David Jackson (some skeptical readers would call their project a

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

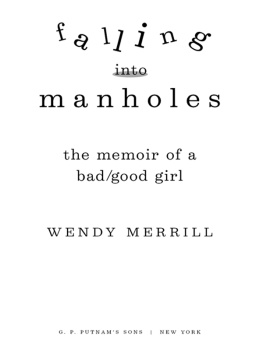

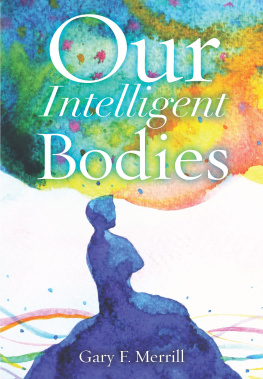

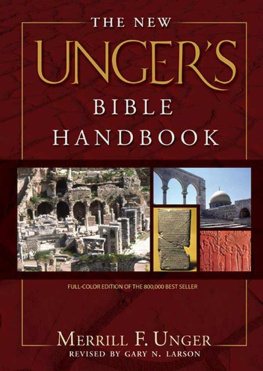

Similar books «A whole world letters from James Merrill»

Look at similar books to A whole world letters from James Merrill. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book A whole world letters from James Merrill and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.