Smithsonian Series in Ethnographic Inquiry

Ivan Karp and William L. Merrill, Series Editors

Ethnography as fieldwork, analysis, and literary form is the distinguishing feature of modern anthropology. Guided by the assumption that anthropological theory and ethnography are inextricably linked, this series is devoted to exploring the ethnographic enterprise.

ADVISORY BOARD

Richard Bauman (Indiana University), Gerald Berreman (University of California, Berkeley), James Boon (Princeton University), Stephen Gudeman (University of Minnesota), Shirley Lindenbaum (New School for Social Research), George Marcus (Rice University), David Parkin (University of London), Roy Rappaport (University of Michigan), Renato Rosaldo (Stanford University), Annette Weiner (New York University), Norman Whitten (University of Illinois), and Eric Wolf (City University of New York)

1988 Smithsonian Institution

All rights reserved

Edited by Michelle K. Smith

Designed by Linda McKnight

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

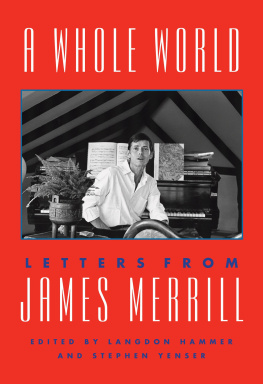

Merrill, William L.

Rarmuri souls

(Smithsonian series in ethnographic inquiry)

Bibliography: p.

1. Tarahumara IndiansReligion and mythology.

2. Tarahumara IndiansSocial life and customs.

3. Indians of MexicoChihuahuaReligion and mythology.

I. Title. II. Series.

F1221.T25.147 1988 299.78 87-62623

ISBN 087474-684-1

eBook ISBN: 978-1-935623-51-9

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

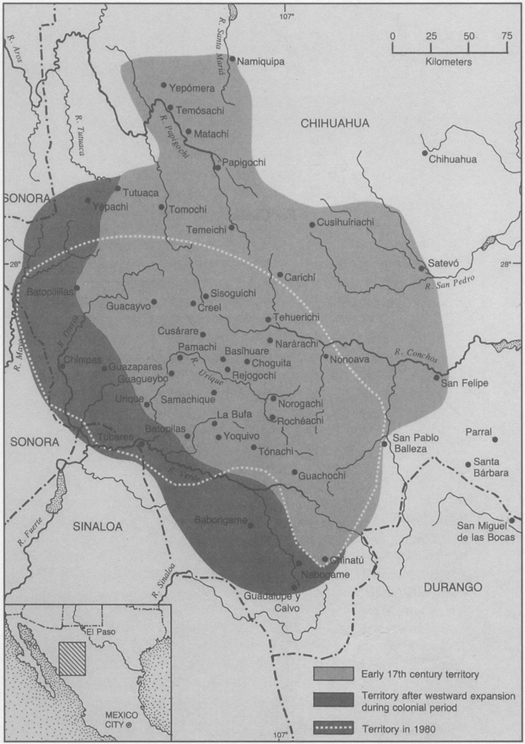

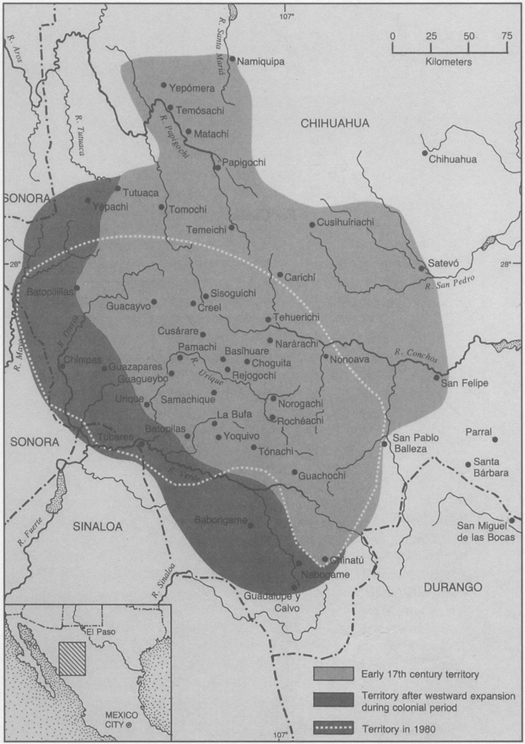

Frontispiece: The Rarmuri homeland.

After Pennington 1983: 277.

All photographs were taken by the author except where noted in the caption.

v3.1

For Cecilia

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1 .

Rarmuri Knowledge

CHAPTER 2 .

The Rarmuri

CHAPTER 3 .

Rarmuri Sermons and the Reproduction of Knowledge

CHAPTER 4 .

The Concept of Soul

CHAPTER 5 .

Curing Practices

CHAPTER 6 .

Death Practices

CHAPTER 7 .

Conclusions

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

RARMURI ORTHOGRAPHY

The Rarmuri speak three distinct dialects, distinguished from one another on the basis of phonology, syntax, and vocabulary. Miller (1983:table 8) designates these dialects as Western, Eastern, and Southern. Millers Eastern Rarmuri is labelled by Burgess (1984) as the Central Dialect and is the dialect spoken by the Rarmuri among whom I lived.

The phonemes of Eastern, or Central, Rarmuri are as follows (Pennington 1983:276):

| voiceless stops and affricate: | p, t, (represented here as ch), k, and (glottal stop) |

| voiced stops: | b, g |

| voiceless fricatives: | s, h |

| nasals: | m, n |

| liquids: | r (flap), l |

| semi-vowels: | w, y |

| vowels: | i, e, a, o, u |

The values of the vowels are very close to those in Spanish. Stress is phonemic. For more detailed discussions of Rarmuri phonology, see Brambila ([1980]), Lionett (1972), and Burgess (1984).

CHAPTER

1

RARMURI KNOWLEDGE

Evil, for them, is not sin. To the Tarahumara, there is no sin: evil is loss of consciousness. The high philosophical problems are more important to the Tarahumara than the precepts of our Western morality.

For the Tarahumara are obsessed with philosophy; and they are obsessed to the point of a kind of physiological magic; with them there is no such thing as a wasted gesture, a gesture that does not have an immediate philosophical meaning. The Tarahumara become philosophers in exactly the way a small child grows up and becomes a man; they are philosophers by birth.

Antonin Artaud, avant garde French writer and dramaturgist, composed this glowing testimony in 1936, following a months stay among the Rarmuri, or Tarahumara, as he and other outsiders have known them (1976: 1011; cf. Schneider 1984). For Artaud, his journey from Paris to the Rarmuris remote mountain homeland in northern Mexico was a pilgrimage. He came in search of the primeval principles of the cosmos with which Western society had lost contact, believing that the Indians of Mexico, especially less assimilated groups like the Rarmuri, could provide him access.

The Rarmuri did not disappoint him. They allowed Artaud to participate in their peyote ceremony and, by his account, revealed to him their esoteric knowledge of the universe. He portrayed their lives as pervaded by philosophy. From his perspective, philosophy in general and Rarmuri philosophy specifically did not exist exclusively in the form of thoughts and words but was immanent in the world, embedded in objects and nonverbal acts. Thus, he argued, the two-pointed, sometimes white, sometimes red headbands of the Rarmuri revealed that within the Tarahumara race the Male and Female principles of Nature exist simultaneously, and that the Tarahumara have the benefit of their combined forces. In short, he continued, they wear their philosophy on their heads. With their philosophy so objectively present, Artaud could dismiss the claim of many Rarmuri that this arrangement is the result of chance, and that they use the headband simply to hold their hair in place (1976: 8, 11; original emphasis).

As this example suggests, many of Artauds interpretations of the Rarmuri are suspect, but it must be remembered that his intentions were primarily artistic, not ethnographic (Schneider 1984; Hayman 1977). His essays provide some interesting observations on Rarmuri life at the time of his visit, but his insights into the culture are colored by his efforts to achieve personal enlightenment and confirmation of his own elaborate conception of the universe. His portrayal of the Rarmuri as philosophers should be regarded in this light, as partly a reflection of what they said and did and partly a product of his theory of philosophy and the universe, which demanded that they be. At the same time, by attributing to the Rarmuri a devotion to philosophical rather than material concerns, Artaud hoped to challenge the equation of material poverty with lack of civilization that the Mexican government was using to justify its efforts to assimilate the Rarmuri and other Native groups.

While his desire to defend the Rarmuris interests is laudable, Artauds assessment of their philosophical inclinations contrasts dramatically with the conclusions of many anthropologists who have investigated this area of Rarmuri life. Undoubtedly the most radical stance on these issues was taken by Robert Zingg, who in 1930 and 1931 undertook nine months of fieldwork among the Rarmuri in cooperation with Wendell Bennett (Bennett and Zingg 1935). About the same time as Artaud was praising the Rarmuri as philosophers, Zingg (1937) characterized them as Philistines, an eminently practical people with a materialistic but realistic orientation to a fairly inhospitable natural environment. Such an orientation, he suggested, obviated the development of the higher interests of mankind, like art, music, and literature. Their indigenous religion was remarkable only in its unrelieved drabness (1942: 88) and was accompanied by a mysticism so crude as to be scarcely rationalized into simple intelligibility and by dreams that were crass, material, and commonplace (1937: 16). For Zingg, even their personalities were wooden, and he found no evidence of tenderness, affection, or caressing (1937: 1415). Only through drinking and participation in the colorful ceremonies introduced by Catholic missionaries were they able, he felt, to escape the dreary world provided by their culture.