THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

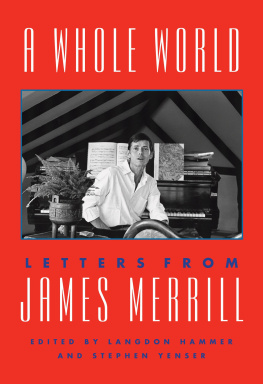

Copyright 2015 by Langdon Hammer

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf,

a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York,

and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada,

a division of Penguin Random House, Ltd., Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks

of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hammer, Langdon, [date]

James Merrill : life and art / Langdon Hammer. First edition.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-375-41333-9 (hardback) ISBN 978-0-385-35308-3 (eBook)

1. Merrill, James, 19261995 2. Poets, American20th centuryBiography. 3. Gay

authorsUnited StatesBiography. 4. Gay menUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

PS 3525. E 6645 Z 674 2015

811.54dc23

2014029325

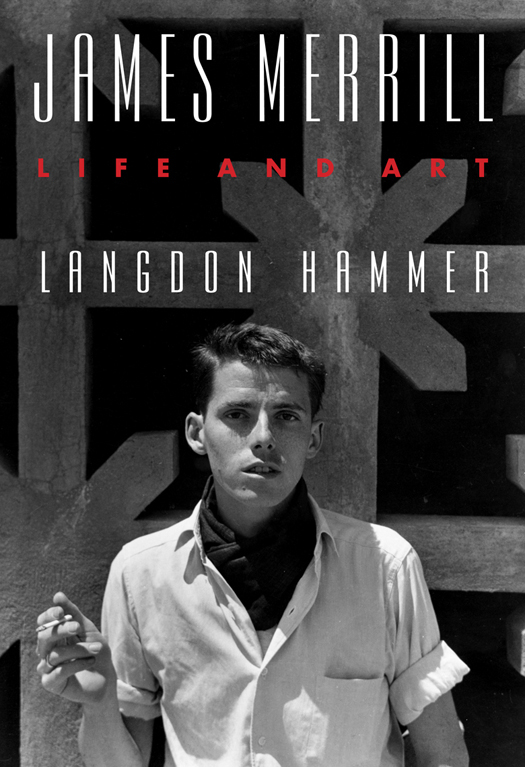

Front-of-cover photograph: James Merrill at Rhodes, May 1950, by Kimon Friar.

Courtesy of The American College of Greece, Attica Tradition Educational Foundation.

Cover design by Chip Kidd

v3.1

For Uta

Diese Tage

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

I merely live to work. Thats James Merrill replying to David Kalstone. Merrill had been needling him about how slow a writer he was, and Kalstone, a professor of literature, defended himself: Some of us have to work for a livingreferring to how little time he had left over after teaching.

Typical of Merrill to turn a clich on its head. Typical of him to pack a serious statement into a quip. As his friend pointed out, he had no need to work: the wealth he was born to ensured that. But rather than freeing him from work, his money allowed him to devote himself to the work he wanted to do. It was a kind of workthe writing of poetrythat drew on and shaped the rest of his life, giving meaning and design, a tone and a style, to everything he did. Poetry made me who I am, he commented on another occasion, slyly reversing the usual relation between maker and made.

Merrill sounds in these remarks like Oscar Wilde, the subversive master of antithesis, for whom the self was not a natural fact but material to be fashioned, like a work of art. He also sounds like his father, Charles Merrill, who made his fortune working very hard on Wall Street. Indeed, strange to say, Merrill resembled both of these self-made men. He created a version of Wildes aesthetic lifestyle, updating the artist-dandys role for late-twentieth-century America, and he brought to the project an intensity of industry his father would have understood.

The teenage Merrill wanted to be like Wilde; it was only a phase, though a phase he would build on more than outgrow. He was energized by a sense of artistic vocation and, almost as if they were the same thing, the secret recognition that he was homosexual. He didnt expect his father to be pleased on either countnot that he was about to say anything to anyone, even to himself in the privacy of his diary, about the homosexual part. He was still freshly wounded from his parents divorce, after which hed sided with his injured mother, Hellen Ingram, who had been the muse of his poetry in childhood. After the divorce, the boy had been packed off to boarding school. His home was broken; it was lost. Poetry and love both seemed like ways to create a more beautiful and durable one.

Why do we read poets lives? To better understand their poetry, yes, although thats not at all the only reason. Samuel Johnsons Lives of the English Poets, which essentially invented this kind of book, were commissioned as prefaces to editions of poetry by Milton, Pope, and others. But Johnsons Lives soon cut loose from the poems they introduced, and circulated as best sellers in their own right. In effect, the poet had become a new type of person: a hero of the interior life, as exemplary in his domain as the soldier, scientist, politician, and saint were in theirs. His charge was to discover and unfold, through artful words and long labor, what was within him, and within anyone and everyone in potential.

That was the idea, the ideology or myth, behind the life Merrill was choosing; by definition he would have to live it in his own way. He approached life as an experiment, the novelist Allan Gurganus, a friend, says about him. It was a possibility, not just an entitlement. Poetry was about possibility: it enabledand requiredhim to make his own meanings. After college, there would be no office to go to, no definite rules for how to become a poet or how to behave like one. The years lay open before him, a book of fresh, blank pages.

In his twenties, he considered plausible options. Like many poets of his era, when English Departments were expanding and creative writing became a staple of the American college curriculum, he tried teaching, but only briefly. In the early 1950s, he played the part of a Jamesian expatriate in postwar Europe, roaming galleries, gardens, and opera houses; he went into psychoanalytic treatment in Rome. When he returned to New York, he made friends with poets and painters in the downtown avant-garde, and flirted with a career writing for the theater. Eventually he found his way by moving with David Jackson, an aspiring novelist, into a third-floor apartment in a commercial building in Stonington, a town on the Connecticut coast. Tiny Stonington offered not much more than the essentials: a chance to write poetry every day and live with his lover largely unobserved.

Right and even inevitable as it seems in retrospect, the choice was unlikely at the time. But perhaps any choice of life a gay man made was going to seem unlikely. Society will not condone it, his mother had warned him about his homosexuality early on, as if that should be reason enough to change his ways. Yet Hellen had a point: to be queer in the 1940s and 1950s in America, even if you happened to be white and wealthy, made you vulnerable to scorn, social exclusion, blackmail, political suspicion, arrest, bullying, or worse brutality. Increasingly American society would, in some contexts, condone it, but his mother never did. Even as he achieved the public success she craved for him, which he must have hoped would legitimate his whole life in her eyes, her son could never forget that his mother hated the fact that he was gay.

Of course, being gay (not a term Merrill used until the 1970s) never meant just one thing. He lived his experiment against the shifting backdrops of the closet, gay liberation, and AIDS, the vocabulary, options, and conditions for leading a queer life changing with the times and with the locales in which he found himself. In the 1950s, in Stonington, hidden in plain sight in the center of town, he and Jackson created a miniature pleasure palace filled with curios, paintings by friends, and souvenirs from their travels. Local types and summer people orbited around them. The atmosphere mixed Jane Austen and E. F. Benson (the author of classic camp novels about characters named Lucia and Mapp)the comedy, intrigues, and epiphanies of daily life set down in Merrills chatty, fluent letters, and sometimes worked into poems.