This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1926 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

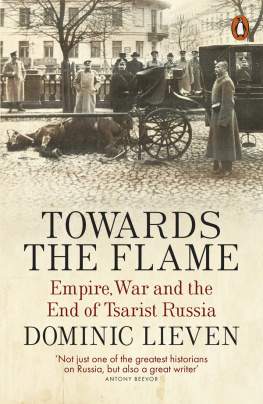

Toward the Flame

A WAR DIARY

By HERVEY ALLEN

Illustrated by LYLE JUSTIS

PREFACE

I HAVE tried to reproduce in words my experience in France during the great war. There is no plot, no climax, no happy ending to this book. It is a narrative, plain, unvarnished, without heroics, and true. It is what I saw as nearly as memory has preserved it, and I have set it down as a picture of war with no comment, except a very little here and there by way of explanation. This book shows how it looked over there.

The narrative covers the drive from the Marne to the Vesle during the fateful months of July and August, 1918, from about July first to August fourteenth. It gives a glimpse of some of the fighting about Chteau-Thierry and Fismes, but above all, it shows how we lived and died, ate, cooked, looked, thought and felt during that time. It is the intimate detail of life at the front as I saw it, and pretends to be nothing more. As a personal narrative told in the first person it is only natural that I appear in it myself.

About half of this material was written in a long letter from a hospital in France immediately after the events which it relates. The rest was set down in 1919 just after my return to the United States when the memories were still so strong as to be almost photographic.

In reading over this account again six years after the war, I find that I was mistaken at times as to the reasons for certain troop movements and disciplinary measures, and in one or two instances even as to my exact whereabouts on a given date. But I have not changed the text in the light of after knowledge, as the preservation of the exact state of mind and even of the prejudices of the times and place are part of the books essential verity and have perhaps a minor value in themselves. In some places , for obvious reasons, personal names have been slightly changed and some military terms and objects have been spoken of in everyday language.

It is a purely personal narrative. Those who look for a discussion of military policies or tactics will be disappointed. This book is not propaganda of any kind. It is much more than that; it is a picture of war, broken off when the film burned out.

HERVEY ALLEN.

NEW YORK,

December, 1925.

PREFACE TO THIS EDITION

SINCE Toward the Flame was first published in the spring of 1926 there have been several editions, including a number of reprints.

In a very quiet manner, unchampioned, unaccompanied by anything but the best critical commentthat of one reader to anotherthe book has gradually taken its place as one of those volumes by an American about the World War, which for one reason or another continues to be widely read. So gradual was the process, however, that the author himself would not have been aware of it had it not been for a constant trickle of letters from readers all over the country. Nevertheless, over thirty thousand copies have now been sold, the last reprint is exhausted, and another is called for. The publishers have therefore taken the opportunity of providing a new format for the volume, which, it is hoped, will be found for several reasons to be more attractive than the old.

In particular it is thought that the illustrations of Mr. Lyle Justis will not only help to bring home to the reader the reality of the scenes here described, but what is more difficult, serve to make evident the general spirit animating those Americans who participated in the great Allied offensive of the summer of 1918.

The artist himself took part as a soldier in the events he depicts. He knows his types, his locale, and his atmosphere. His illustrations are therefore the result of imagination drawing upon genuine personal experience.

So rapidly have the details and peculiar aspects of the scenes of the Great War tended to fall into oblivion that it seems essential to point out at this writing that Toward the Flame is not a story about professional soldiers glorifying the exploits of some particular unit. It is merely that of one of many of the National Guard units of the American army. But as such, it is that cross section of the citizens in arms, and actually engaged in battle, which the narrator observed and did his best to report .

In the preface to earlier editions, which is here included, and which I wish new readers would read, I refer to the fact that This story ends where the film burns out. That is quite literally true.

It was not the object of this book merely to relate a personal adventure. I tried, insofar as anyone can, to eliminate the big I of little ego and to substitute for it only the first person singular of the fellow who happened, under certain circumstances, to be around. Hence, I ended the story with the night attack on the village of Fismette, when most of the defenders of that place had ceased to exist. If I did not inflict upon my readers certain personal sufferings and physical indignities that followed, it was because I felt that they were important to me alone. In other words, I meant this to be a report of what I saw on the battle line, and when the fighting ends the story stops.

In answer, however, to many letters and innumerable questions as to what did happen to me, I can now, after sixteen years, hasten to add that in the early morning hours after the attack, and in the company of one sergeant, I managed to return to headquarters where I was promptly tagged by our regimental surgeon and sent to a base hospital.

To him, and to that surgeon, whoever he was, who in a certain field hospital saved my eyes from the effect of mustard gas and tended other injuries, I should like at this time to express what the word gratitude only too coldly conveys. But that is another story.

And since the story of behind the lines is essentially different from the story of the battlefront this book has nothing to do with the former.