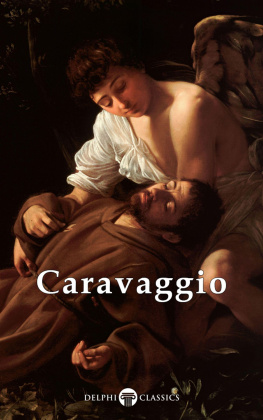

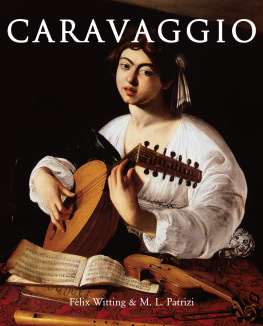

H E WAS THIRTY-NINE when he died, in the summer of 1610 . He had been in exile, on the run, for the last four years of his life. He slept fully clothed, with his dagger by his side. He believed that his enemies were closing in on him and that they intended to kill him.

He was wanted for murder in Rome, for stabbing a man in a duel that was said to have begun over a bet on a tennis game. It was not the first time that he had been in trouble with the law. He had been sued for libel, arrested for carrying a weapon without a license, prosecuted for tossing a plate of artichokes in a waiters face, jailed repeatedly. He was accused of throwing stones at the police, insulting two women, harassing a former landlady, and wounding a prison guard. His contemporaries described him as mercurial, hot-tempered, violent.

Michelangelo Merisi, known as Caravaggio, was among the most celebrated, sought after, and highly paid painters in Rome. But not even his influential patrons could arrange for the murder charge to be dismissed. After the crime, he fled to the hills outside the city, and then to a village near Palestrina, where he could have lived safely under the protection of the Colonna family, who were among his patrons, and beyond the range of papal jurisdiction. But the bucolic small town must have seemed dull compared to the chaotic street life of the Campo Marzio, to the taverns, the whorehouses, the gang fights, andmost important for Caravaggiothe fierce, energizing competition with his fellow artists, most of whom he despised.

In Rome, he had seized every opportunity, however impolitic or inappropriate, to criticize his contemporaries and to advance his own ideas about the true purpose of artideas he held with the force of a fanatical conviction and that fueled his erratic behavior, his vertiginous descent from wealth into vagrancy, and his ultimate self-destruction. In retrospect, his contempt and impatience seem more understandable: the frustration of a genius surrounded by a great deal of very bad, very popular, very lucrative and respected art.

During the years he spent in flight, he painted almost constantly. And despite or because of the impossible pressures and makeshift working conditions, his art became even more ambitious, darker and more deeply shadowed. Months after the murder, he turned up in Naples, where he completed two major altarpieces and a number of smaller canvases. But once again he grew restless. Perhaps he was being followed, or perhaps he just thought so. In any case, he felt that he had no choice but to leave the city.

Sometime before, he had challenged his former employer and subsequent rival, Giuseppe Cesari, the Cavaliere dArpino, to a duel. The cavaliere had replied that, as much as he would have liked to fight, his status as a Knight of Malta prevented him from participating in pointless street brawls with men who, not being knights, were beneath him. Now, as Caravaggio decided where to go after Naples, the old insult may possibly have factored in to his decision to sail to Malta. He would become a Knight of Malta, he would join the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, a confraternity of soldiers who took monastic vows of poverty and chastity and who pledged to defend the Christian faith. Also he may have heard that the Maltese were seeking a painter to decorate the Cathedral of Saint John in Valletta.

His experience in Malta established a pattern that would be repeated throughout his exile from Rome. Because his fame had preceded him, and thanks to his contacts in the Maltese capital, he was welcomed by the local nobility and given prestigious commissions. He painted furiously, brilliantly. Driven by his belief in the importance of working from nature, he employed live models whom he posed in theatrical tableaux re-creating scenes from the New Testament and from the lives and deaths of the early Christian martyrs. Always, he reimagined these dramas in novel ways that reached beyond the conventions of art to tap directly into the power and resonance of biblical narrative, and to engage the viewer with an immediacy that made these dramas of suffering and salvation seem comprehensible and convincing. Often ahead of his patrons, the people responded to an art that reminded them that these miracles had transpired neither in primary colors, nor in brilliantly hued paintings of sanitized saints and celestial fireworks, but in dusty streets and dark rooms much like the streets and rooms in which they lived.

Inevitably, his work was widely discussed, passionately admired or hated, and his fees increased along with his reputation. As he traveled, awaiting the pardon that might enable him to return to the capital, he seemed to have found a way of surviving, of supporting himself and practising his art away from the reliably generous patrons and the distracting intrigues of Rome. And then, just as inevitably, something would go wrong.

So, in Valletta, he succeeded in having himself appointed a Knight of Maltanot an easy task, since the honor was mostly reserved for sons of the nobility. Doubtless his knighthood had something to do with the influence of his supporters in Rome, and with the magnificent portrait he did of the grand master of the Knights of Malta, Alof de Wignacourt. But again the artists situation took a sudden and drastic turn for the worse. Caravaggio insulted a fellow knight, a superior, and was imprisoned in the notoriously escape-proof fortress, Vallettas Castel SantAngelo.

Caravaggio escaped. Pursued, he believed, not only by the popes men but now also by a posse of vengeful Maltese knights, whose military code of honor had been grievously affronted, he fled to Sicily. In Syracuse, he was reunited with Mario Minniti, a close friend and fellow artist who had served as Caravaggios model and with whom he had lived in Rome. During his sojourn in Syracuse, Caravaggio painted The Burial of Saint Lucy for the church of Santa Lucia, where the virgin martyr had originally been entombed.

In the winter of 1608 -, he left Syracuse for Messina, where he promptly received a commission to paint The Resurrection of Lazarus . According to one early biographer, he destroyed the first version of the painting when he felt that it had been underappreciated by the doltish provincials who were now his principal patrons. Later he repainted it, presumably assisted by the same local laborers he asked to carry the corpse he used as the model for the dead Lazarus. After a fight with a local schoolmaster who alleged that Caravaggio stared too fixedly at the young male students, he left Messina for Palermo, where he painted a Nativity, which was later destroyed in an earthquake.

From Palermo he returned to Naples. There, he was woundedkilled, people saidin a fight at a tavern. His face was slashed and so disfigured that he was nearly unrecognizable; it was assumed that the attack had been arranged by his old enemies from Malta. While he recovered, he began a series of smaller paintings for the influential Romans who were pleading his case. Ultimately, he received word that he had at last been granted an official pardon for the 1606 murder.