CONTENTS

For my father, Jack

T HE E NGLISHMAN MOVES IN A SLOW BUT DELIBERATE SHUFFLE, knees slightly bent and feet splayed, as he crosses the piazza, heading in the direction of a restaurant named Da Fortunato. The year is 2001. The Englishman is ninety-one years old. He carries a cane, the old-fashioned kind, wooden with a hooked handle, although he does not always use it. The dome of his head, smooth as an eggshell, gleams pale in the bright midday Roman sun. He is dressed in his customary mannera dark blue double-breasted suit, hand tailored on Savile Row more than thirty years ago, and a freshly starched white shirt with gold cuff links and a gold collar pin. His hearing is still sharp, his eyes clear and unclouded. He wears glasses, but then he has worn glasses ever since he was a child. The current pair are tortoiseshell and sit cockeyed on his face, the left earpiece broken at the joint. He has fashioned a temporary repair with tape. The lenses are smudged with his fingerprints.

Da Fortunato is located on a small street, in the shadow of the Pantheon. There are tables outside, shaded by a canopy of umbrellas, but the Englishman prefers to eat inside. The owner hurries to greet him and addresses him as Sir Denis, using his English honorific. The waiters all call him Signore Mahon. He speaks to them in Italian with easy fluency, although with a distinct Etonian accent.

Sir Denis takes a single glass of red wine with lunch. A waiter recommends that he try the grilled porcini mushrooms with Tuscan olive oil and sea salt, and he agrees, smiling and clapping his hands together. Its the season! he says in a high, bright voice to the others at his table, his guests. They are ever so good now!

When in Rome he always eats at Da Fortunato, if not constrained by invitations to dine elsewhere. He is a man of regular habits. On his many visits to the city, he has always stayed at the Albergo del Senato, in the same corner room on the third floor, with a window that looks out over the great smoke-grayed marble portico of the Pantheon. Back home in London, he lives in the house in which he was born, a large redbrick Victorian townhouse in the quiet, orderly confines of Cadogan Square, in Belgravia. He was an only child. He has never married, and he has no direct heirs. His loverson this subject he is forever discreethave long since died.

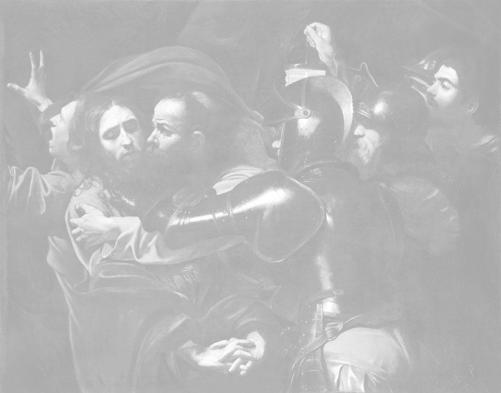

Around the table, the topic of conversation is an artist who lived four hundred years ago, named Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Sir Denis has studied, nose to the canvas, magnifying glass in hand, every known work by the artist. Since the death of his rival and nemesis, the great Italian art scholar Roberto Longhi, Sir Denis has been regarded as the worlds foremost authority on Caravaggio. Nowadays, younger scholars who claim the painter as their domain will challenge him on this point or that, as he himself had challenged Longhi many years ago. Even so, he is still paid handsome sums by collectors to render his opinion on the authenticity of disputed works. His verdict can mean a gain or loss of a small fortune for his clients.

To his great regret, Sir Denis tells his luncheon companions, hes never had the chance to own a painting by Caravaggio. For one thing, fewer than eighty authentic Caravaggiossome would argue no more than sixtyare known to exist. Several were destroyed during World War II, and others have simply vanished over the centuries. A genuine Caravaggio rarely comes on the market.

Sir Denis began buying the works of Baroque artists in the 1930s, when the ornate frames commanded higher prices at auction than the paintings themselves. Over the years he has amassed a virtual museum of seicento art in his house at Cadogan Square, seventy-nine masterpieces, works by Guercino, Guido Reni, the Carracci brothers, and Domenichino. He bought his last painting in 1964. By then, prices had begun to rise dramatically. After two centuries of disdain and neglect, the great tide of style had shifted, and before Sir Deniss eyes, the Italian Baroque had come back into fashion.

And no artist of that era has become more fashionable than Caravaggio. Any painting by him, even a small one, would be worth today many times the price of Sir Deniss finest Guercino. A Caravaggio? Perhaps now as much as forty, fifty million English pounds, he says with a small shrug. No one can say for certain.

He orders a bowl of wild strawberries for dessert. One of his guests asks about the day, many years ago, when he went in search of a missing Caravaggio. Sir Denis smiles. The episode began, he recalls, with a disagreement with Roberto Longhi, who in 1951 had mounted the first exhibition in Milan of all known works by Caravaggio. Sir Denis, then forty-one years old and already known for his eye, spent several days at the exhibition studying the paintings. Among them was a picture of St. John the Baptist as a young boy, from the Roman collection of the Doria Pamphili family. No one had ever questioned its authenticity. But the more Sir Denis looked at the painting, the more doubtful he became. Later, in the files of the Archivio di Stato in Rome, he came across the trail of another version, one he thought more likely to be the original.

He went looking for it one day in the winter of 1952. Most likely it was morning, although he does not recall this with certainty. He walked from his hotel at a brisk pacehe used to walk briskly, he saysthrough the narrow, cobbled streets still in morning shadow, past ancient buildings with their umber-colored walls, stained and mottled by centuries of smoke and city grime, the shuttered windows flung open to catch the early sun. He would have worn a woolen overcoat against the damp Roman chill, and a hat, a felt fedora, he believes. He dressed back then as he dresses nowa starched white shirt with a high, old-fashioned collar, a tie, a double-breasted suitalthough in those days he carried an umbrella instead of the cane.

His path took him through a maze of streets, many of which, in the years just after the war, still lacked street signs. He had no trouble finding his way. Even then he knew the streets of central Rome as well as he knew Londons.

At the Capitoline Hill, he climbed the long stairway up to the piazza designed by Michelangelo. A friend named Carlo Pietrangeli, the director of the Capitoline Gallery, was waiting for him. They greeted each other in the English way, with handshakes. Sir Denis does not like being embraced, and throughout his many sojourns in Italy he has largely managed to avoid the customary greeting of a clasp and a kiss on both cheeks.

Pietrangeli told Sir Denis that he had finally managed to locate the object of his search in, of all places, the office of the mayor of Rome. Before that, the painting had hung for many years in the office of the inspector general of belle arti, in a medieval building on the Via del Portico dOttavia, in the Ghetto district of the city. The inspector general had regarded the painting merely as a decorative piece with a nice frame, of no particular value. The original, after all, was at the Doria Pamphili. After the warPietrangeli did not know the precise detailssomeone had moved it to the Palazzo Senatorio, and finally to the mayors office.

Pietrangeli and Sir Denis crossed the piazza to the Palazzo Senatorio. The mayors office lay at the end of a series of dark hallways and antechambers, a spacious room with a high ceiling and a small balcony that looked out over the ancient ruins of the Imperial Forum. There was no one in the office. Sir Denis spotted the painting hanging high on a wall.

Next page