Copyright 2015 by Niccol Capponi

Translation copyright 2015 by Andr Naffis-Sahely

First Melville House printing: November 2015

Melville House Publishing

46 John Street

Brooklyn, NY 11201

and

8 Blackstock Mews

Islington

London N4 2BT

mhpbooks.com facebook.com/mhpbooks @melvillehouse

ISBN: 978-1-61219-460-8

eBook ISBN: 978-1-61219-461-5

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015955589

Design by Christopher King

The publication of this volume has been supported by a translation grant of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Questo volume ha beneficiato di un contributo alla traduzione assegnato dal Ministero degli Affari Esteri italiano

v3.1

In memory of Vincenzo Pertile (19202010),

who was a teacher in every sense of the word

Anghiari

June 29, 1440

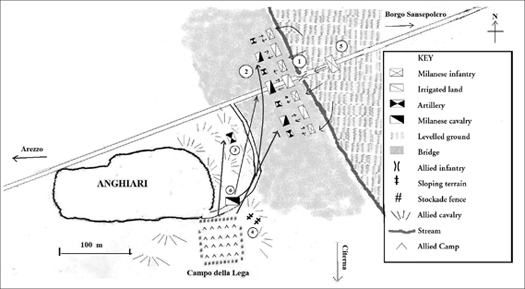

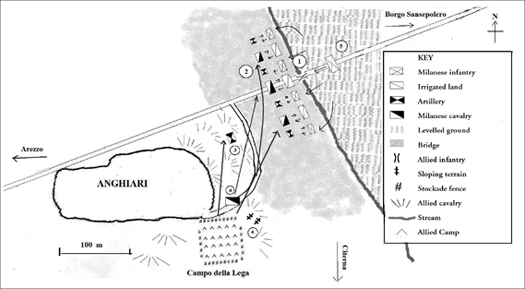

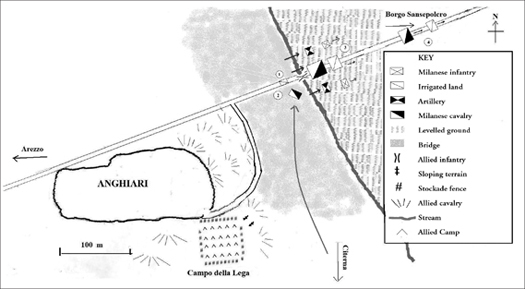

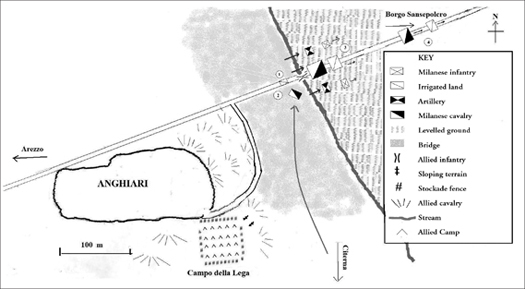

3:00 p.m. (1) Milanese troops, including a strong contingent of mounted infantrymen, head towards the bridge, with the aim of attacking the allied camp. (2) Having spotted the cloud of dust raised by the enemy army, Micheletto Attendolo gallops off to defend the bridge with only a few men. (3) Neri Capponi and Bernardetto de Medici sound the alarm in the allied camp, simultaneously co-ordinating the counter-attack.

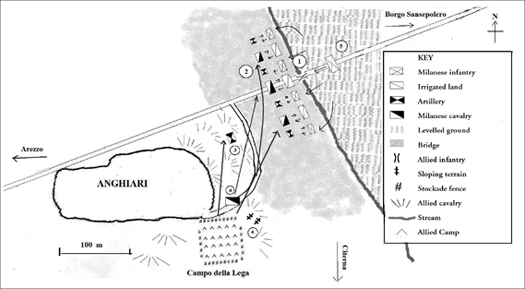

3:155:30 p.m. (1) The Milanese cross the bridge, also thanks to their infantrys outflanking manoeuvre and line up on the levelled ground. (2) Piero Giampaolo Orsini and Simonetto da Castel San Pietro rush to Attendolos aid. The fight between the knights and foot soldiers grows particularly fierce as the Milanese try to break through enemy lines. (3) The Genoese crossbowmen are deployed on the hills slopes, and target Niccol Piccininos troops from their positions. (4) The allies drag a few bombards out of their camp to enfilade the Milanese armys left flank. (5) Piccinino deploys his reserves to create a breach in the enemy front. (6) The galloping intervention of the allies reserves re-establishes the balance between the armies.

5:307:00 p.m. (1) Astorre Manfredi brings his men forward to repel the allies, creating a hole in the Milanese ranks. (2) The arrival of the Leagues saccomanni turns the tide in the allies favour, and they manage to push the ducal troops back over the stream. (3) Although Piccinino has fewer troops at his disposal, he manages to close his ranks again and hold out for a little longer. (4) Exhaustion, the enemys pressure and the wind blowing dust into their eyes cause the Milanese armys ranks to collapse and they are pursued by the allies right up to Borgo Sansepolcro.

INTRODUCTION

For the sake of a nail the shoe was lost This is how a poem by the English poet George Herbert begins, which I learned as a little boy alongside a host of other nursery rhymes. Starting with the loss of a nail, then the horse, the knight and the battle, the ditty ends with the downfall of a kingdom. Following this sequence of single but interconnected events, Herberts poem is seemingly deterministic, but it actually opens up an endless range of alternate conclusions which were far from unavoidable: the loss of a single nail doesnt necessarily entail the loss of that horseshoe, just like losing a battle wouldnt automatically lead to the downfall of a state. In fact, Herbert focuses on a precise sequence of factual events, and doesnt account for the different outcomes the events in question might have led to.

The events as far as many historians are concerned, these are the domain of dilettantes or journalists, the pornographers of history, who exhibit a morbid curiosity for the most striking facts, but are nevertheless incapable of understanding the profound dynamics of Clios world: the crests of foam that the tides of history carry on their strong backs, according to Fernand Braudels celebrated definition. However, all historianswhether they are providentialists, structuralists, postmodernists, or devout, agnostic or atheisticmust nevertheless reckon with the events, be it to confirm, contradict, or distort them, perhaps even going so far as to deny they ever occurred in the first place. Yet however true it remains that history and events are intimately intertwined, its equally true that historians must routinely deal with substantial gaps in the narratives.

Despite what one might assume, there is still much we dont know even when it comes to the great figures of the past, which we should in theory know everything about. Yet this is perfectly logical if we consider, for example, all the coffee bills which we diligently consign to our trash bins, which, taken together, could tell us a great many things about our habits, revealing information that could prove of the utmost importance to historians if considered alongside other documents. To these we must add our daily actions, which are often forgotten by posterity, even when they involve other people, and simply because nobodyall too rightlythinks it useful to write them down. These days, only a select few keep diaries, and this certainly wont be of help to the work of future scholars.

As a matter of fact, the real problem for historians doesnt lie in the abundance of documents, or lack thereof, but rather in how to interpret what we actually have. This is why it is crucially important to focus on events that almost definitely happened in the past, even if we cannot verify them beyond the shadow of a doubt. The memory of a particular event may have been transcribed by a single individual, and naturally, even if this person had been the most honest person who ever lived, not only would his or her account be constrained by this persons hierarchy of values and priorities, but it would also reflect a limited perspectivethe direct result of the impossibility of omniscience. For example, lets consider a hypothetical conversation between two friends in a room: each of them will have only a limited view of their surroundings and will primarily concentrate on a few words to describe what really sparked their interest. If these friends later transcribed their meeting, a relatively slow-witted reader might find apparently irreconcilable contradictions in both their accounts: the shape of the room could be described as either a square or a rectangle; one of the friends might have noticed that the other often picked his nose, which the other person of course wouldnt have mentioned. Fanatical devotees of deconstruction might then conclude that neither of them was telling the truth, whereas it would simply mean that each friend had merely stated a part of the whole truth. Hence, the historian must seek to find the common elements in both accounts, which will allow him to reconstruct the scene with the greatest possibly accuracy.

However, and keeping in mind the notion of the horseshoe nail, events are never isolated, but rather are links in a causal chain. Some of these links are larger than others and are more immediately evident: these are the pivotal turning points of history. The only example of this in Herberts poem is the loss of the horse, and consequently that of the knight: the missing nail doesnt necessarily lead to the horseshoe falling off, just as the loss of said shoe doesnt trigger the horses fall, and one cannot take it for granted that a single individual could alter the outcome of a battle, which might also end inconclusively in any case. Indeed, the very concept of a decisive battle is often rejected by modern historians, also because stability and continuity are more easily dealt with. In spite of this, some clashes exercise a mysterious fascination over us that no historical analysis will be able to dispel: for instance, the battles of Salamis, Hastings, Waterloo, Gettysburg or Stalingradjust to mention a feware seen as moments that altered the course of history, and this ultimately leads to the following question: what would have happened if the Persians, the Saxons, the French, the Confederates or the Germans hadnt been defeated?