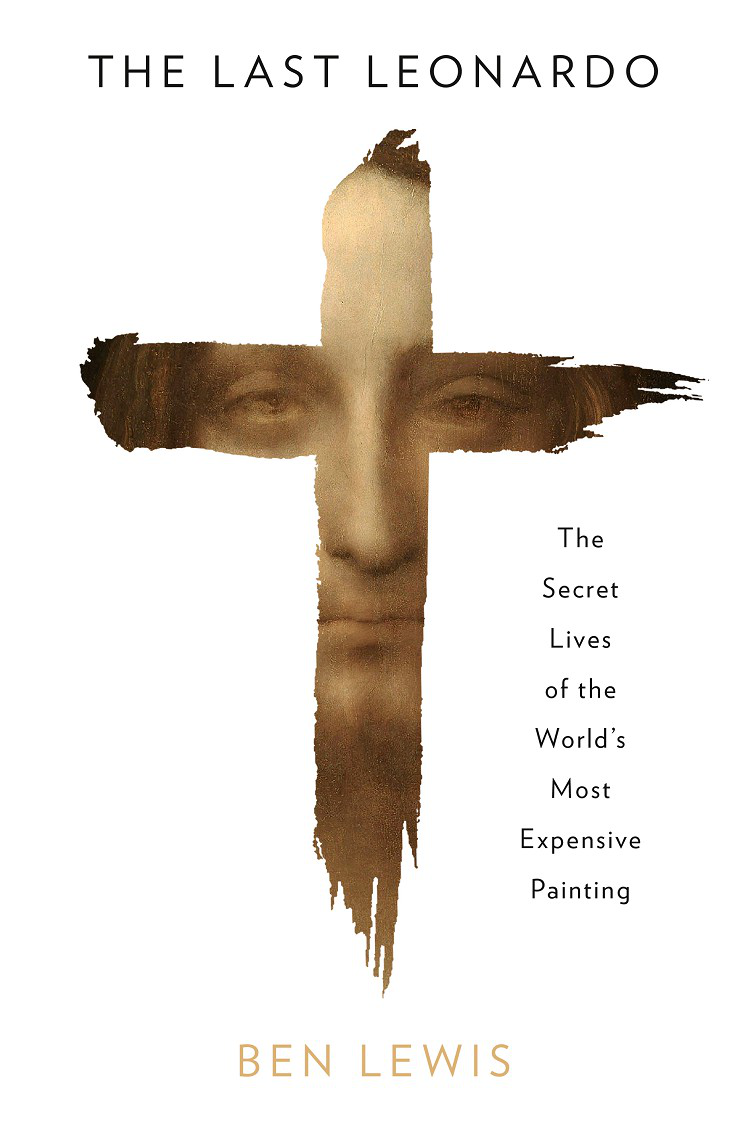

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright BLTV Ltd, 2019

Cover image: Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008313418

Ebook Edition April 2019 ISBN: 9780008313432

Version: 2019-04-15

To Niamh and Lorcan

Having wandered some distance among gloomy rocks, I came to the entrance of a great cavern, the likes of which I had never seen. I stood for some time in front of it in astonishment. I bent over, resting my left hand on my knee, while shading my eyes with my right. I squinted, shifting first one way and then the other, to see whether I could ascertain anything inside, but this was hindered by the deep darkness within. After having remained there some time, two contrary emotions arose in me: fear and desire fear of the threatening dark cavern, desire to see whether there were any marvellous thing within it.

LEONARDO DA VINCI

The politics of Leonardo scholarship are like any other politics except that so far no blood is shed.

SIR KENNETH CLARK

Signs form a language, but not the one you think you know.

ITALO CALVINO

It aint where ya from, its where ya at

ERIC B. & RAKIM

PROLOGUE

Centuries ago, in an age when the world was still ruled by monarchs and dukes and countesses dressed in velvet and golden brocade, there lived a man of illegitimate birth, as warm-hearted in his disposition as he was boundless in his curiosity, fierce in his intellect and skilful with his hands. This man was engineer, architect, designer, scientist and painter the greatest painter, say many, who had ever lived. A genius, say others, who had brought the modern world into being. His pictures were both real and ideal, more beautiful than anything ever seen before. He studied the natural world in its tiniest details, from the leaves on trees to the paws of bears, and in its hidden rules, such as the proportions of the human face and body. He looked far and peered close, sketching the pale horizons of mountains and peeling back mens skin so he could see the muscles and arteries that lay beneath.

But this artist was also an enigma. When he died, he left riddles and tricks for those who wished to cherish his memory and preserve his legacy. Sometimes his masterpieces were painted with colours that faded or crumbled even before he had finished the work; others were sealed with varnishes that made them darker and darker with the passing of decades. Like many great men, he seemingly cared little for the gift God had given him, painting little and slowly, and instead burying himself in the notebooks that he filled with scribbles of magnificent ideas, which he had neither the patience nor the technology to build. He made fewer paintings than any other great artist in history, and even fewer have survived: at most only nineteen.

In the centuries that followed his death, people yearned to possess more of his work than they had; there were never enough pictures by this artist to satisfy the worlds craving for his images. Myths and theories proliferated about the pictures that had been lost, hidden or painted over. In the institutes of learning devoted to the arts, there was no higher calling than the study of this artists work; and among those scholars who studied his art, there was no greater glory than discovering a lost or forgotten painting, drawing or sculpture by his hand.

The stakes were high and, if you fell on them, sharp. The artist never signed or dated his work. He had many pupils, whom he taught to paint as skilfully as himself, in exact imitation of his style, and they produced hundreds of copies of his works. Occasionally, a contemporary recorded, he would add the final touches himself a fact which further confused posterity. Knowing the risks, the wisest scholars sought to resist the temptation to identify a lost painting, preferring to explore an overlooked fragment or a half-finished sentence in the artists notebooks. But, eventually, many succumbed to the allure of buried treasure. The corridors of art history libraries were full of the wailing ghosts of professors whose lifes work had been destroyed by the chimera of a new Leonardo they believed they had found; the headlines, news reports and celebrations that greeted their discovery were replaced within years, if not months, by academic derision for what was now revealed to be a forgery or copy, betrayed by paint that had been applied too loosely, or colours pronounced too dominant, or in which there was a trim in the costume that belonged to an incongruous era.

This artist, Leonardo da Vinci, was just like the sun. He was the brightest planet in the art history cosmos. Scholars who flew too close to him found their books suddenly aflame and themselves engulfed in the fire of ambition. Yet still their attempts continued

CHAPTER 1

Robert Simon had plenty of legroom on his flight to London in May 2008. He was flying first class, an unusual luxury for this comfortably successful but unostentatious Old Masters dealer, president of the invitation-only American Private Art Dealers Association. During moments of transatlantic turbulence he cast a glance down the aisle at one of the first class cabins cupboards, where he had been given permission to stow a slim but oversized case.

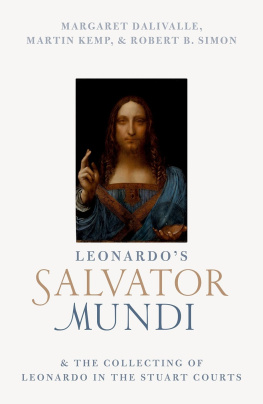

It contained a Renaissance painting, 66cm high and 45cm across, of a half-figure, to use the old-fashioned art historical term, of Christ. The portrait composition showed the face, chest and arms, with one hand raised in blessing and the other holding a transparent orb. One reason Simon was worried about the painting was because he had not been able to afford the insurance premium he had been quoted for it. He had bought it three years earlier for around $10,000 or so he had told the media but it was now thought to be worth between one and two hundred million dollars.

Far from being the life of luxury many people imagine, dealing in art can be a precarious existence even at the highest levels, because selling expensive paintings is, well, very expensive. Top-end galleries have vertiginous overheads. Walls have to be repainted for each show, catalogues printed, wealthy collectors wined and dined. Simon had spent tens of thousands of dollars restoring the boxed painting, and had not yet seen a penny return.

Solidly built, medium height, Jewish, fifty-something, soft-spoken, polite, Robert Simon is the kind of person who believes that modesty and understatement are rewarded by the higher forces which direct our lives. He projects a modest, pleasant, but slightly brittle calm. Loose lips sink ships, he likes to say, repurposing a slogan emblazoned on American propaganda posters in the Second World War to the business of art.