The Politics of Fame

Also by Eric Burns

NONFICTION

Broadcast Blues

The Joy of Books

The Spirits of America: A Social History of Alcohol

Infamous Scribblers: The Founding Fathers and the Rowdy Beginnings of American Journalism

The Smoke of the Gods: A Social History of Tobacco

Virtue, Valor, and Vanity: The Founding Fathers and the Pursuit of Fame

All the News Unfit to Print: How Things Were and How They Were Reported

Invasion of the Mind-Snatchers: Televisions Conquest of America in the Fifties

1920: The Year That Made the Decade Roar

The Golden Lad: The Haunting Story of Quentin and Theodore Roosevelt

Someone to Watch over Me: A Portrait of Eleanor Roosevelt and the Tortured Father Who Shaped Her Life

When the Dead Talked: How the Smartest Minds in the World Fell under the Spell of Psychics

FICTION

The Autograph: A Modern Fable of a Father and Daughter

Mid-Strut: A Novel

PLAYS

Mid-Strut

Rise and Fall

The Politics of Fame

ERIC BURNS

Rutgers University Press

New Brunswick, Camden, and Newark, New Jersey, and London

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Burns, Eric, author.

Title: The politics of fame / Eric Burns.

Description: New Brunswick, New Jersey : Rutgers University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018003443 (print) | LCCN 2018028895 (ebook) | ISBN 9781978800618 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781978800700 (epub) | ISBN 9781978800694 (web pdf) | ISBN 9781978800687 (mobi)

Subjects: LCSH: United StatesCivilization. | United StatesSocial life and customs. | Popular cultureUnited States. | FameSocial aspectsUnited States. | CelebritiesUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC E161 .B87 2019 (print) | LCC E161 (ebook) | DDC 306.0973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018003443

A British Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the British Library.

Copyright 2019 by Eric Burns

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. Please contact Rutgers University Press, 106 Somerset Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901. The only exception to this prohibition is fair use as defined by U.S. copyright law.

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

www.rutgersuniversitypress.org

Manufactured in the United States of America

To Linda Konner

Who made an exception for me;

I dont know where Id be without it

Fame is a bee.

It has a song

It has a sting

Ah, too, it has a wing.

Emily Dickinson

Contents

Most books about fame tell of the people who possess itathletes and actors; singers and comedians; politicians and news readers; and those who cannot be categorized except as celebrities, their pedigrees uncertain, their reality shows unreal. This book is different. It is, as much as possible, the story of those who bestow fame, and why. The Politics of Fame looks back on shifting trends in the culture and shifting currents in the human psyche that have compelled so many Americans to kneel before the thrones of so many strangers in so many different ways for so many years past and so very many more to come.

Amen.

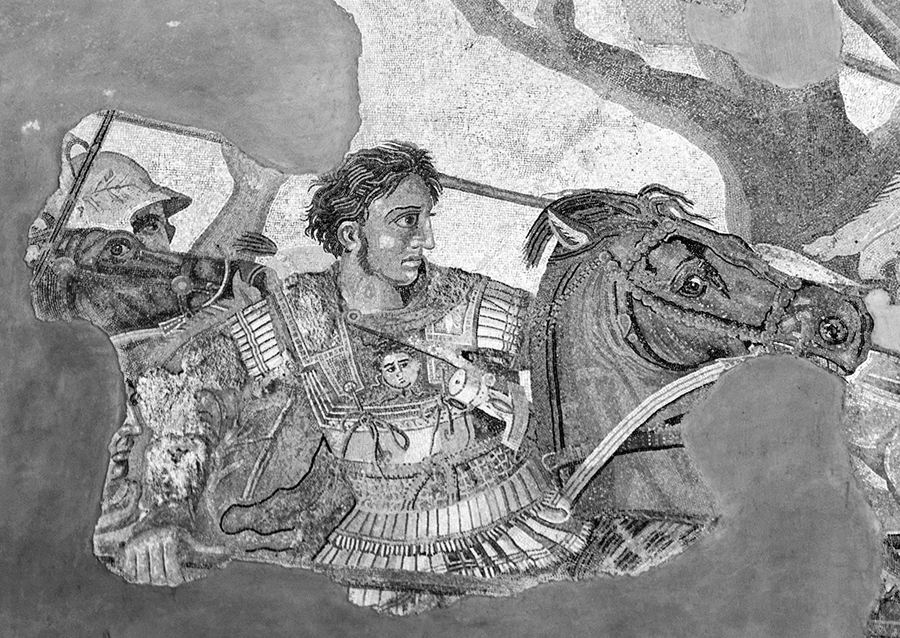

Naples, National Archaeological Museum, Alexander Mosaic. Berthold Werner. Licensed under CC BY 3.0.

Alexander the Great was the worlds first celebrity, identified as such by his name and trained as such by two of the greatest figures of the ancient world. His father, Philip II of Macedon, was an esteemed soldier and leader of troops, possessed of uncommon wisdom, organizational skills, and the bearing of a man who expected to be obeyed. After the battle of Chaeronea in 338 A.D., which Philips forces won, he governed more people than had ever been under the rule of one man before: In effect [he] had a stranglehold on the Aegean Greek world and deprived the Greek cities in his power of their cherished freedom and autonomy. Such ruthless application of power made Philip a controversial figure, far more despised than admired.

His son would be a leader of a different sort.

Among the reasons was that, beginning at the age of thirteen, his mentor was Aristotle, the most scholarly of Greek philosophers at the time. He found a young man uncommonly curious about the world around him, an informal student of plants and animals and the infrastructure of legislation. Aristotle gave his pupil needed breadth, making of him a humanist, a man with respect for culture and learningand not just the culture and learning of his own people.

The curriculum that the philosopher devised for the boy was far-reaching, ranging from morals to politics, and from metaphysics to medicine. Alexander became especially adept at the latter: For when any of his friends were sick, he would often prescribe them their course of diet, and medicines proper to their disease.

Aristotle also encouraged his students military ambitions. It was a matter of faith with Aristotle, writes the historian David Fromkin, that Greece could rule the world if it were politically united.

When his son was twentyhaving already been a fighting man for four years, and at times a vicious onePhilip was assassinated, and Alexander became the Macedonian king. Despite his youth, he was prepared by then not only to unite Greece but also to conquer all the other peoples over whom his father had one day planned to reign. It would be no small feat, as the empire bequeathed to Alexander now extended well beyond Greece, reaching all the way east to India. Nonetheless, Aristotles star pupil set out to establish his authority, subjugating a number of populations who were diverse, rambunctious, and to all appearances mutually repellant.

Even though his goals were imperialistic, becoming all the more so in the years remaining to him, Alexander would remain as devotedly studious as he had been as a boy. For my part, he wrote to Aristotle from one of his many encampments, I had rather surpass others in the knowledge of what is excellent than in the extension of my power and dominion. If he exaggerated, he did not do so by much. Plutarch wrote that Alexander had a violent thirst and passion for learning, and this increased as time went on.

Sometimes Alexander would don the garb of his new subjects who had just fallen to his sword, to show thatthe strenuousness of his struggles with them notwithstandinghe held the traditions of his vanquished peoples in high regard. At times he would grant audiences to some of them, usually men of lower station. He would treat them with regard, explaining the goals of his administration, answering their questions, and making them feel as important as their nominal superiors in the conquered nations hierarchy. He would insist on lenient sentences for people who had committed crimes out of desperation, reduce taxes in a year of poor crop yields, and authorize both the time and expense for public works projects when he believed they were needed. It was important to him that the lands he governed be fairly treatedeven more fairly, if possible, than they had been under their native rulers.

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.