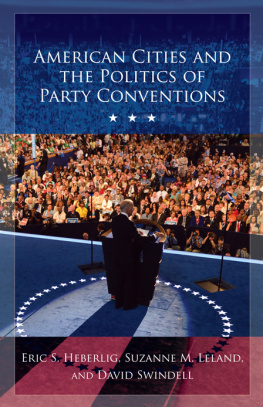

American Cities and the

Politics of Party Conventions

American Cities and the

Politics of Party Conventions

Eric S. Heberlig, Suzanne M. Leland,

and David Swindell

On the cover: Vice President Joe Biden speaks on the final night of the DNC in Charlotte, North Carolina, September 6, 2012. Photograph by Todd Sumlin (). Courtesy of the Charlotte Observer.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2017 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Dana Foote

Marketing, Michael Campochiaro

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Heberlig, Eric S., 1970 author. | Leland, Suzanne M., 1971 author. | Swindell, David, 1966 author.

Title: American cities and the politics of party conventions / Eric S. Heberlig, Suzanne M. Leland, and David Swindell.

Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016045128 (print) | LCCN 2017007997 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438466392 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781438466408 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Political conventionsUnited StatesPlanning. | Political conventionsSocial aspectsUnited States. | City planningUnited States.

Classification: LCC JK2255 .H43 2017 (print) | LCC JK2255 (ebook) | DDC 324.273/156dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016045128

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Preface

The origins of this project should be easy to guess. On February 1, 2011, the Democratic National Committee announced that Charlotte would host the 2012 Democratic National Convention. Having just lived through North Carolinas new status as a competitive state in the 2008 presidential election, and the media attention that came with it, the potential to add the media saturation of a party convention on top of it seemed overkill. How could we get any academic research done? We couldnt study the convention since conventions dont matter anymore, according to the conventional wisdom in political science. Then Gene Alpert of The Washington Center provided the direction we needed when he observed that no one had studied conventions from the citys perspective. Indeed, cities do a tremendous amount of work to recruit and implement presidential nominating conventions, and parties have developed extensive site selection processes to choose the best host. The parties and the cities partner to make themselves look good in the national and international media and to avoid repeats of the 1968 Chicago Democratic National Convention. We sought to understand how and why parties and cities developed their partnerships during the conventions and the implications for understanding how cities operate.

Our vision from the beginning was that this project would be of interest to multiple audiences, and our academic backgrounds reflect that multidisciplinary approach. Heberlig studies political parties, elections, and campaign finance. Leland studies public administration, city planning, and intergovernmental relations. Swindell studies urban policy and economic development, particularly with regard to sports.

This book will appeal to those interested in urban management, policy and planning, economic development, party politics, interest groups, and general public administration. It should also be of interest to community leaders such as members of the chamber of commerce, city council members, county commissioners, mayors, city and county staff, and reporters who wonder: Why did the convention end up there? How does a city pull this off? Is it really worth it for our city to do this?

We owe our thanks to numerous people who have contributed to this project. First, we thank Rye Barcott and Elizabeth Terry of Duke Energy for supporting local universities engagement with the 2012 DNC and for generously providing the funds for us to partner with Winthrop Universitys Social and Behavioral Research Lab and its director, Scott Huffman, to survey residents of Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, about their experiences with the convention. The analyses of the citizens views on paying for mega-events, the political effects of conventions, and residents evaluations of mega-event development strategies in . Finally, we thank our families for their patience with this (seemingly) never-ending book project. We dedicate this book to them:

Tracy, Colin, Mena, and Ellie

Eric

Dan and Max

Suzanne

Jennie and Alex

David

Who Wants Circus Politicus ?

The political convention demands organizational skill and manipulative geniusboth of which qualities are exceeding useful in democratic government.

Pendleton Herring, 1965

Professor Herring was referring to presidential candidates in this quote, but its relevance to them has declined as presidential nominating conventions have largely ratified decisions made by primary and caucus voters since the reforms of the 1970s. Today, we argue the quote more aptly applies to the cities that host the conventions. Cities develop bid strategies and compete with one another to entice the national party committees to choose them. Cities are at the center of complex intergovernmental and public-private networks to plan and implement political conventions. Cities decide how much to invest in infrastructure to attract tourism generally and mega-events specifically as part of their economic development efforts. When presidential nomination conventions or other mega-events come to town, cities can benefit from the short-term boost in delegate spending and the longer-term reputational benefits brought by the national and international media attention. While the potential benefits of mega-events are relatively clear, how and why cities weigh the costs and benefits of pursing them change over time, how they implement these strategies differently than a normal tourism promotion strategy, and how local politicians (as opposed to the city collectively) can benefit from them are more open questions.

Voters in state primaries and caucuses have made that decision; the convention makes their selection official. We argue that the politics of the convention is now outside the conventional hall. The story of contemporary presidential nominating conventions is less about the nomination of presidential candidates than about the partnership between the parties and the cities to capture the media attention and advance their own goals. Conventions inseparably linked a city and a political party in their quests for national respect (Sack, 1987a).

A Partnership: Cities and Parties

In the process of recruiting and implementing a political convention, the host city develops many organizational partnerships and faces the critical task of coordinating them. The most important of these partnerships is with the national party committee that seeks a city as its agent to implement its convention. The partys goal for the convention is to motivate its delegates to work hard to elect the party nominee and to create a weeklong infomercial for viewers to persuade them to vote for the party nominee. The party seeks a partner in the host city to whom it can delegate the logistics and transaction costs so it can keep its attention (and that of the media) on the partys message of unity, accomplishment, and promise. The party needs the city to entertain the delegates and media representatives, keep demonstrators out of the news, and fix inevitable glitches quickly and competently so that the only story occurs on the podium.