Paper Politics: Socially Engaged Printmaking Today

edited by Josh MacPhee

with essays by Deborah Caplow and Eric Triantafillou

ISBN: 978-1-60486-090-0

Library of Congress Control Number: 2009901385

This edition 2009 PM Press

Individual copyright retained by the respective contributors

Sue Coe: We are All in the Same Boat

2005 Sue Coe

Courtesy of Galerie St. Etienne, New York

PM Press

POBox 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

PMPress.org

Cover and internal design by Josh MacPhee/Justseeds.org

Printed in the United States.

Paper Politics

Socially Engaged Printmaking Today

Josh MacPhee

with essays by Deborah Caplow and Eric Triantafillou

table of contents

Josh MacPhee

Deborah Caplow

Eric Triantafillou

Politics on Paper

Josh MacPhee

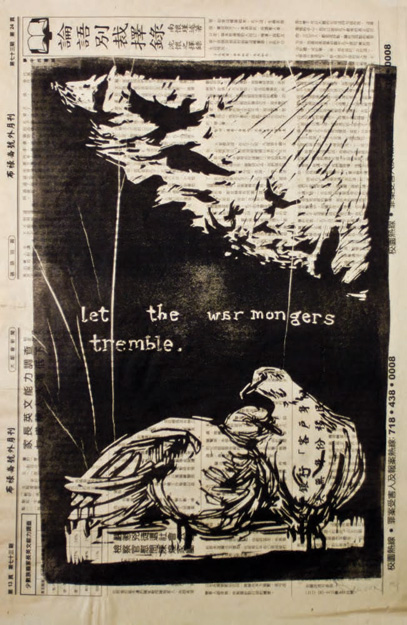

EVERY PRINT IN THIS BOOK was printed by human hands: linoleum was carved, copper was scratched, cardstock was cut, photo paper was dipped in developing chemicals. These types of traditional printmaking are not the dominant form of communication today. They cant compete with billboards or bus ads, never mind television or the Internet. Yet these printmaking methods remain vital, maybe even because of their anachronistic existence. We rarely see any evidence of the human hand in our visual landscape, just digitally produced dot patterns and flickering electronic images. This gives handmade prints affective powerstenciled posters pasted on the street or woodcuts hanging in a window grab the eye; they jump out at us because of their failure to seamlessly fall in line with the rest of the environment.

There is a contradiction here. Our prints can stand out from the pack, but only if we print them in small batches by hand. If the goal of political printmaking is communicating ideas, and we want those ideas to reach as many people as possible, does it really make sense to be printing seventy handmade posters in the age of mass production? This is just one of the many questions and conundrums that continually bring me back to printing by hand. There is something in the act of spreading ink on a wood block or pulling ink through a screen with a squeegee that can create a powerful connection between printer and print and audience. What this connection can do I am unsure of. Ive asked many of the artists in this book why they still continue to print by hand, and youll find their answers throughout this book.

My own interest in printmaking began in the street. I became interested in street stenciling after seeing stenciled art in the political comic book World War 3 Illustrated, and quickly became obsessed with the art form. For fifteen years I regularly stenciled prints directly onto streets across the country. Ive also tried my hand at linocuts, and am currently an active screen printer. At the core of my interest in all these printmaking forms is their simplicity, accessibility and inexpensive charm. You can make hundreds of copies of a print in a couple of hours, and then hand them out to friends, sell them for cheap, or paste them on the street. A quick look at main streets in most urban areas and its clear Im not the only one who feels there is power in public displays of printmaking.

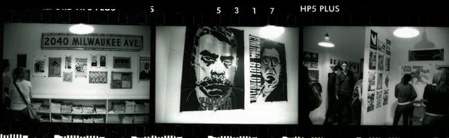

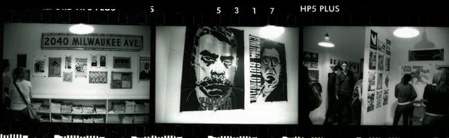

Paper Politics Chicago, 2004

photographs by Brandon Bauer

Paper Politics started out as an exhibition of political prints, and has now taken the form of this book, but it has always also been a project of building communities. In early 2004, I organized the first Paper Politics art show in Chicago as a fund raiser for a small group of social movement-minded street artists I was a part of called the Street Art Workers (Streetartworkers.org). It was an experiment. I had a loose network of contacts with fellow political print and poster makersmost of them, like me, young with little formal training in printmaking. I also had a hunch that there was a wide audience for this type of scrappy, socially-engaged printmaking. Paper Politics was an attempt to actualize both a community of printmakers and a more specific audience for our work than the existing anyone that happens to see it on the street.

A half dozen artist friends from around the Midwest converged on Chicago and helped hang the show, not in an art gallery, but in the offices of the magazine In These Times. This project grew out of the Do It Yourself (DIY) ethic and community, and out of the idea that artists can create their own exhibitions without galleries, professional curators, or wealthy art collectors. Six of the artists that helped (Alec Icky Dunn, Nicolas Lampert, Colin Matthes, Erik Ruin, Shaun Slifer and Mary Tremonte) would go on to become members of the Justseeds Artists Cooperative, an artist-owned and -run collective and online gallery in which I currently participate. (Sixteen of the fifty artists involved in the first show have ended up as members of Justseeds.) The response to the show was overwhelming. Hundreds of people came to the opening, and we sold over $2,000 worth of prints, all for $25 or less. People were literally fighting to get in line to buy political prints. I had never seen anything like it. I still get emails from people who came to that opening night, asking whats happening with Paper Politics and whats going on in this part of the political print world.

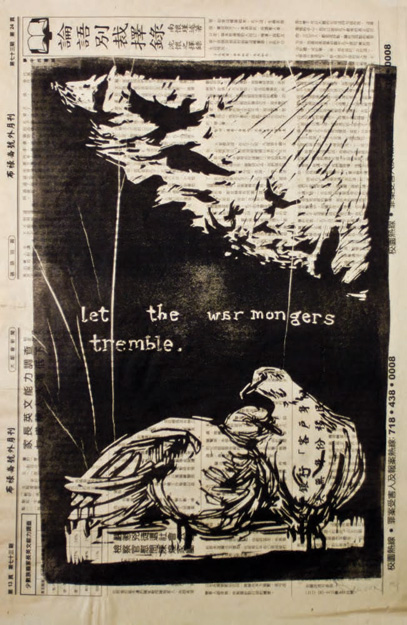

The staff at In These Times not only gave us free space to hang the show, they also ran a couple short features and images from the show in their magazine. Luckily, Joseph Pentheroudakis, then the President of Seattle Print Arts, saw one of the features and contacted me about re-creating the show in Seattle. Together we put out an open call, and through our combined networks of punk rock poster makers and more professional and trained printers, we built a new collection of 174 works by 174 different artists. And unlike the Chicago show, which was almost exclusively made up of do-it-yourself stencils, screen prints and linocuts, Paper Politics now had raw and dirty spray painted stencils on old dumpstered blueprints hanging next to precise and fine art intaglios on Arches paper. The work collected in Seattle became the core of the exhibition and this book. Over the next four years the show has travelled to Brooklyn; Corpus Christi, Texas; Cortland, New York; Milwaukee; Montreal; Portland, Oregon; Syracuse, New York; Richmond, Virginia, and Whitewater, Wisconsin. At each stop it has collected new work. It has shown in community centers, artist-run spaces, university art galleries, and an empty warehouse. Artists have met each other and audiences, and built long-term, nurturing relationships.

Art exhibitions that express clear positions on social issues are rare. They may happen sporadically in major cities, but Ive found that Paper Politics has received an outpouring of interest in smaller cities and non-urban centers. Many of the shows have been organized or hosted by printmakers with work in Paper Politics, and holding events in their locale has allowed them to reach out and connect with like-minded artists. In Milwaukee, the opening was one of the largest ever at the Walkers Point Center for the Arts, and in Richmond dozens of people expressed excitement that there was a show in their town that directly discussed labor issues, the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, struggles around immigration and borders, and problems with the U.S. electoral system.

Next page