Contemporary Native American Artists

Suzanne Deats

principal photography by Kitty Leaken

Contemporary Native American Artists

Digital Edition 1.0

Text 2012 Suzanne Deats

Photographs 2012 Kitty Leaken

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except brief portions quoted for purpose of review.

Gibbs Smith

P.O. Box 667

Layton, Utah 84041

Orders: 1.800.835.4993

www.gibbs-smith.com

ISBN: 978-1-4236-2275-8

To Merida Red Star, 19792008

At the age of sixteen, Merida took on the responsibility of managing the career of her renowned artist father, Kevin Red Star. She fulfilled the job with competence and grace until her untimely death. Merida was the embodiment of the tribal ethic of allegiance, unity, and support that is the essence of Native American art and life. We dedicate this book to the memory of her beauty, her strength, and her loving heart.

Foreword Bruce Bernstein, Ph.D.

I have been involved in Native American arts for a long timenot just with the arts themselves but, much more importantly, with the artists and the people behind the arts: the family, the friends, the new people I meet all the time. Thats the real privilege of the scholarly world I live in. I have learned something of the Native American worldview and understanding of art and our surroundings, and I am continually pleasantly astonished at what I see. I am even more amazed at what I dont know. Each encounter with Native American artists brings new clarity.

These days when I am thinking about art, I think particularly about just being with artists and friends. Art is about that relationship, about doorways and bridges to other worlds. There can be a vast chasm between the Native and non-Native world, and often art serves as a critical linkage. In turn, each artist, each collector, each gallery, each friend has a responsibility to help build and maintain the bridge between those worlds.

Let me just talk about the bridge for a moment, because it remains an accurate and expansive metaphor, simultaneously appropriate and inappropriate. It is appropriate because there is necessarily a vital separation of histories and how each population, indigenous and mainstream, relates to the natural and cultural worlds. But the metaphor also calls into account the fact that we all experience the same world. When we respond well to a piece of art, what we are standing in front of is something that is our own perception. Someone has seen what we have seen; perhaps it is reworked or reinterpreted. We stand there wondering, How did they see what I saw? On the other hand, we could be viewing the piece with a fascination for something we know nothing about.

Thats the bridge. Where the metaphor becomes more literal is that Native American artists today cross back and forth freely on that bridge. There is no longer anyone to restrict them to one side or the other; there is nothing keeping them from participating in whatever part of society they wish to participate in. But what makes this a binary situationappropriate and inappropriate at the same timeis that we are fooled if we think we all inhabit the same world. When we sit and talk to a famous Native artist, we see that we have the same clothes on, that we both got here in our cars or we both flew here. Maybe we attended the same schools, we are eating the same food, we are laughing about a shared experiencewhatever it is, we must realize that despite these commonalities there is still a difference between the worlds.

The group of Native artists that you will see in this book constructed a bridge across that divide. They exhibited their work together, and they urged people to step back and forth across the bridge from the collectors side to the artists side. They presented themselves honestly, thereby creating something I refer to as contextual authenticity. This is not something made-up or fabricated but rather something that is alive and ongoing, continually growing and contracting, changing and staying the same to evolve, to remain vital and relevant. You cant define itits not one person or another, one art form over another. Authenticity is about the way a person fits into the world, the way a person operates in that world. These Native American artists have brought an authentic family ethic to bear in the presentation of their work, and they share it with people from all over the world.

Bruce Bernstein, Ph.D.

Director, Southwestern Association for Indian Arts (SWAIA), Santa Fe

Former Director, Museum of Indian Arts and Culture, Santa Fe

Former Assistant Director for Cultural Resources,

National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Wakeah Jhane, daughter of Jhane Myers, performs a traditional Plains dance in her mothers award-winning beaded Southern Plains buckskin dress. Wakeahs name, which has been in the family for seven generations, is Comanche for finds lost things.

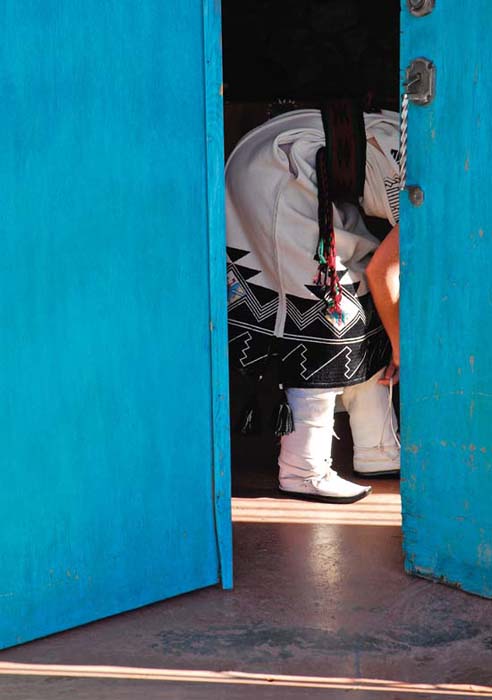

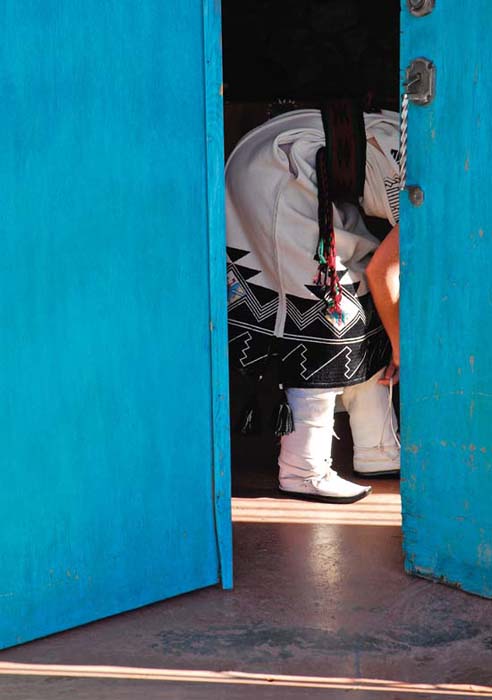

Santa Clara potter Jody Naranjo tightens the leather straps on her moccasins at the Santa Clara Trading Post. She is wearing a traditional manta that was embroidered by her aunt. Jodys extended family of celebrated artists goes back many generations at Santa Clara Pueblo.

Jody Naranjo in her manta, with one of her sgraffito pots during a photo session for Native Peoples Magazine.

Afterward, in street clothes, back at the trading post.

Jody Naranjo opens up her booth at the Santa Fe Indian Market, at 7 a.m. sharp, surrounded by weary customers who have been waiting in line since 5 a.m. for first chance at her pots.

Wakeah Jhane, in her hip street clothes and hat, tightens the laces on her brother Phillips moccasins before he performs the Chicken Dance, a Plains dance that he has finessed at numerous powwows.

Wakeah Jhane, daughter of Jhane Myers, wins Best of Show at the 2008 Indian Market Native Clothing Contest. Here she receives her blue ribbon from the judges on the Santa Fe Plaza while her mother (in white) and sister, Peshawn, look on.