THE INFAMOUS

SOPHIE DAWES

NEW LIGHT ON THE QUEEN OF CHANTILLY

ADRIAN SEARLE

First published in Great Britain in 2020 by

PEN AND SWORD HISTORY

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Adrian Searle, 2020

ISBN 978 1 52671 749 8

Mobi ISBN 978 1 52671 750 4

The right of Adrian Searle to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Or

PEN AND SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

Chapter 1 Fall and Rise: The Smugglers Daughter

Chapter 2 A Life Off-kilter: The Bourbon Aristocrat

Chapter 3 Entrapment: A Web of Outrageous Fortune

Chapter 4 Mnage Trois : Scandal at the Chteau

Chapter 5 Power Grab: Chantillys Queen Assembles Her Court

Chapter 6 Intrigue: Sophies Pact with the Orlans Prince

Chapter 7 A Will of Infamy: The Cond Inheritance

Chapter 8 Tragedy at Saint-Leu: The End of the Cond

Chapter 9 Deadly Suspicions: Suicide or Murder?

Chapter 10 End Games: The Scarred Spoils of Victory

Endnotes

Acknowledgements

Selected Bibliography

Introduction

The Isle of Wight has produced, or been strongly linked with, a cast of truly remarkable women whose extraordinary life stories have fascinated, shocked, amazed and, in some cases, titillated an appreciative audience extending far beyond the shores of the island that was once their home.

These women have included top-drawer characters such as the beautiful Seymour Fleming, Lady Worsley, whose high-octane adulterous sex life scandalised English society late in the eighteenth century and stretched the boundaries of criminal conversation to their absolute limits. At the other end of the scale was dowdy seaside landlady Dorothy OGrady, sensationally sentenced to death for treachery in the Second World War after playing the part of an enemy spy for a giggle.

Their stories are scarcely believable. You could not make them up. And yet they pale in comparison to the tale of Sophie Dawes, the smugglers daughter who experienced the ultimate rags to riches life to rise from abject poverty and the islands workhouse to the dizzying heights of post-revolutionary royal French society, eventually claiming a form of royal status for herself as she ruled the household of a fabulously wealthy Bourbon prince as the unofficial Queen of Chantilly. This was a reign of terror. It led to scandal, an outrageous pact with the King of the French and the very suspicious death of her Bourbon lover.

Further deaths in mysterious circumstances would follow as Sophie ensured her lasting infamy in France. But how could any of this have happened? There have been some outstanding biographies, in France and Britain, tracing the extraordinary life story of Sophie Dawes. The most reliable were the works, in the early decades of the twentieth century, by the French writer Violette Montagu and the English author Marjorie Bowen. They provide magnificent sources of reference today for anyone looking afresh at Sophies story.

Yet there were gaps in these otherwise excellent works. There was a particular need to know more about Sophies formative years in order to establish a clearer understanding of the triggers to her later infamy. This book sets out to fill those gaps and provide new perspectives on some of the storys key events.

Sophie Dawes has never had a good press. But her unique place in history has always provided the basis for a good a very good story. Hopefully this book has used that basis to good effect.

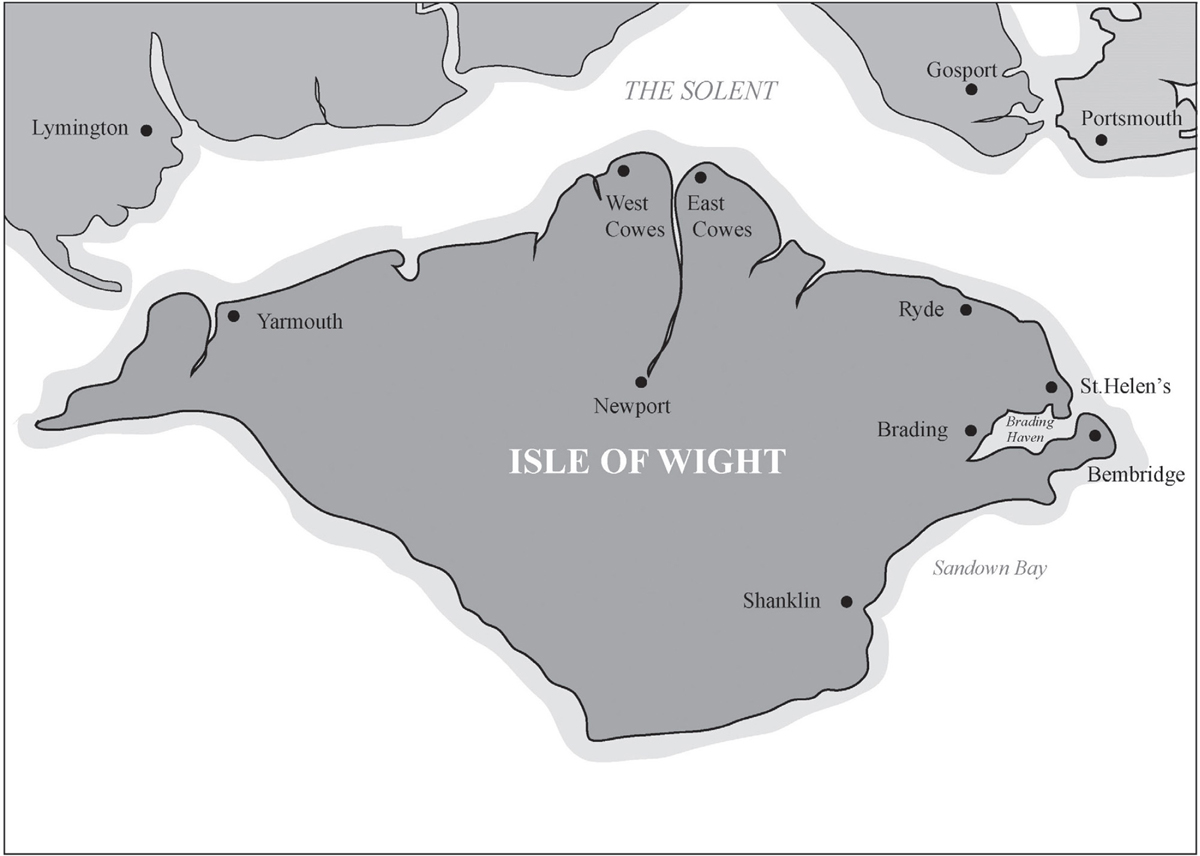

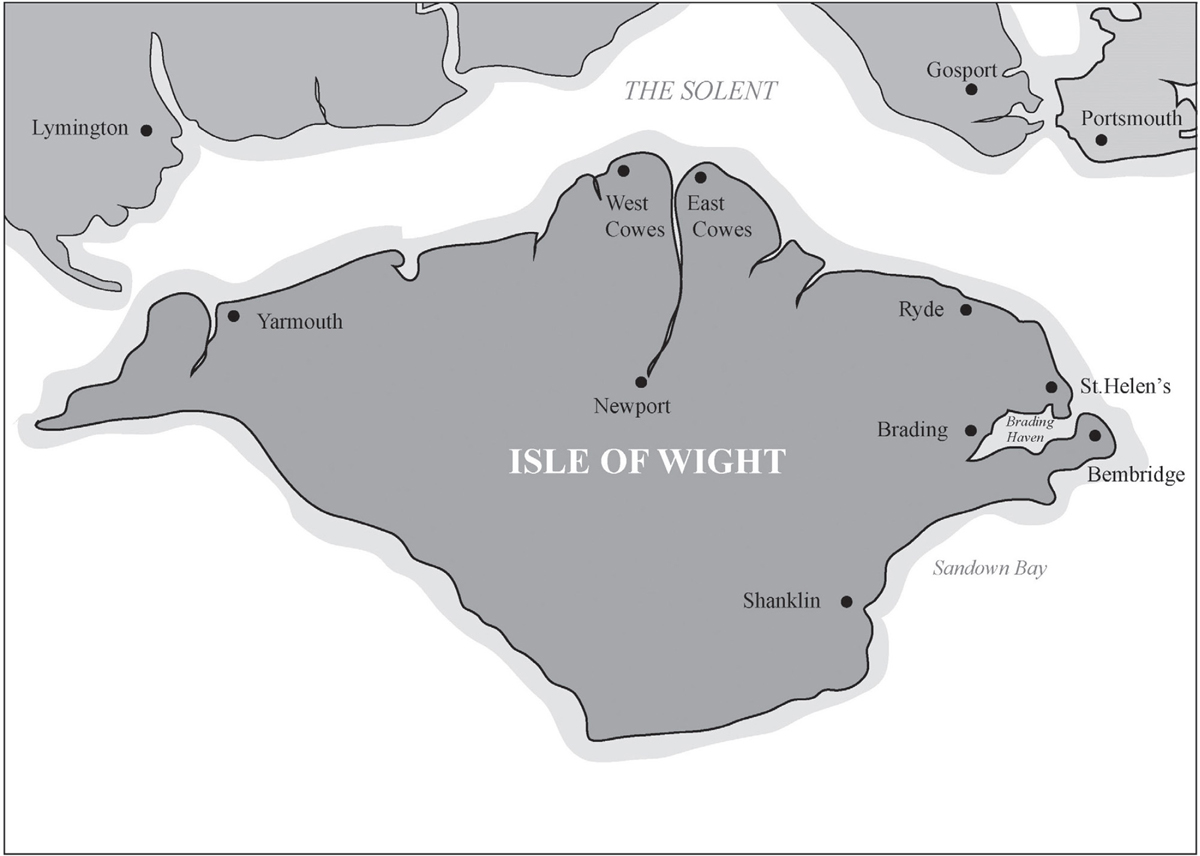

Map of the Isle of Wight showing principal locations during the period of Sophia Daws childhood in the late eighteenth century and her St Helens birthplace near Brading Haven before its reclamation from the sea. (Sarah Searle)

Chapter 1

Fall and Rise:

The Smugglers Daughter

The formative years of the Englishwoman whose rags to riches story would so spectacularly stamp an indelible mark on the history of post-revolutionary France held little in the way of promise. Indeed, there was nothing at all to suggest, at best, anything other than a life of drudgery and servitude; one devoid of recognition beyond the narrow confines of a humble existence amid the relative obscurity and rural remoteness of her birthplace on the Isle of Wight.

Any biographical account should, of course, begin with the date of the subjects birth. Yet all attempts to establish with certainty the year, let alone the precise date, of Sophie Dawes low-key start to a life which would prove to be anything but modest or restrained have been frustrated by the absence of a baptismal record in infancy the usual source for determining the age of a child born in England before the introduction of birth registration in 1837 and a subsequent catalogue of conflicting documentary evidence. We are left with the vague conclusion that she was born sometime between 1789 and 1793. The commemorative plaque which today adorns the front wall of her village home in Upper Green Road, St Helens proclaims that the future Queen of Chantilly was born there around 1792. It seems a safe bet.

Name styling, too, is something of a problem when recounting Sophies story. Neither her given name nor the family name corresponds precisely to how she is remembered today. Called Sophia at birth the adaptation to Sophie, the Gallic form of the name, was a much later consequence of her time in France she was the eighth of the ten children born to fisherman Richard Daw, popularly known and always recalled as Dicky, and his wife, the former Jane Callaway. Despite early biographical insistence that theirs was a union never blessed with the Not untypically for the period, she was one of only four offspring of Dicky and Jane to reach maturity, each of the remaining six children succumbing to a tragically early death as an infant or young child.

The first of the Daw children was James Richard, believed to have been born at St Helens in August 1777, although if his birth was sanctified by baptism there are no surviving records to confirm this. James would emerge safely from childhood. Not so fortunate were William, whose birth in July 1779 was followed almost exactly two years later by his death, and Richard, a Christmas Day arrival in 1780 who survived only until his thirteenth month in 1782. By December of the following year Jane had given birth once more, this time to a girl, Mary-Ann, the second child destined for a full life. Sadly, this was in stark contrast to Sarah, born in 1785, who lived for just nineteen months, dying three days after Christmas in 1786, five months after the birth of a second Richard, who seems to have lived only long enough to acquire a name. More heartbreak was to follow for Jane Daw following the birth in July 1788 of another daughter, Charlotte. By the start of November 1791 Charlotte was dead, aged 3.