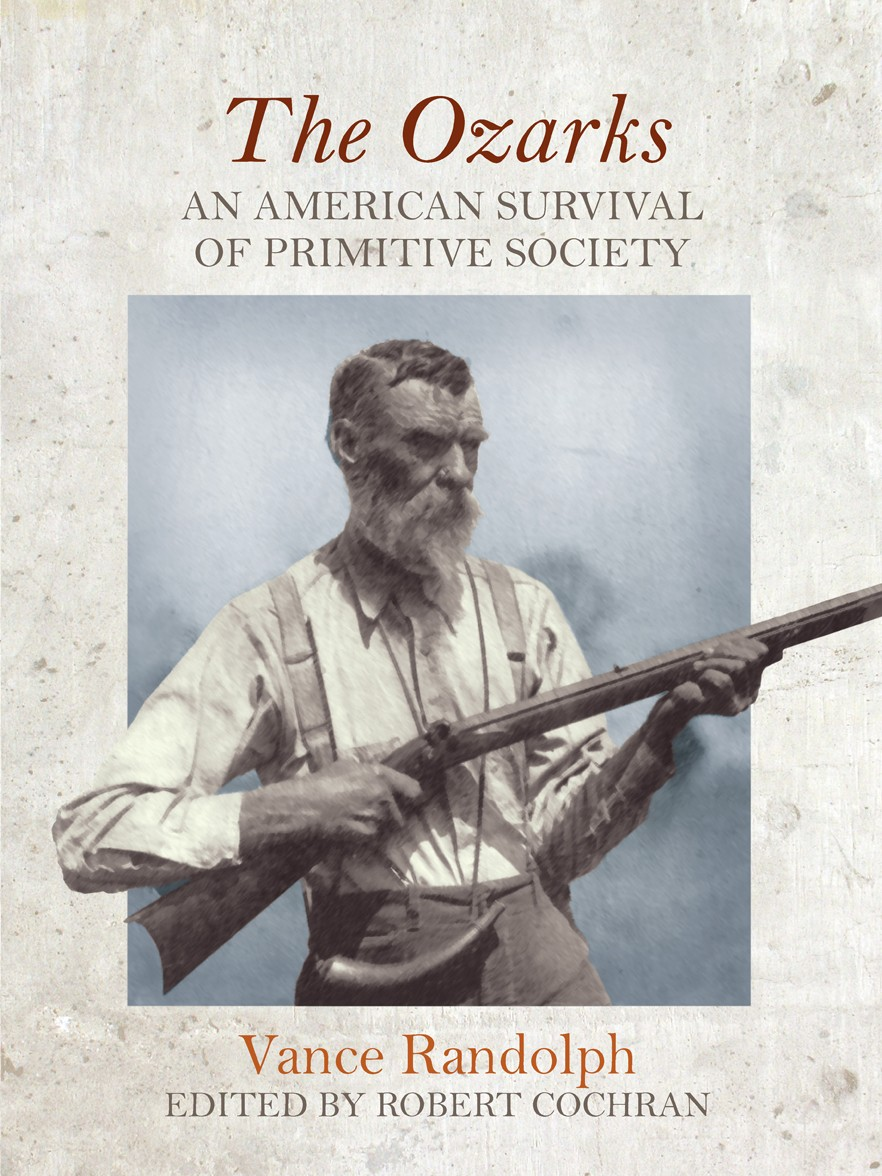

THE OZARKS

Chronicles of the Ozarks

Brooks Blevins, General Editor

Copyright 2017 by The University of Arkansas Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-1-68226-026-5

e-ISBN: 978-1-61075-608-2

21 20 19 18 17 5 4 3 2 1

Designed by Liz Lester

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016960150

To M.R.

SERIES EDITORS PREFACE

IT WOULD TAKE SOME DOING to convince me that anyone has ever been more connected to a region than Vance Randolph was (and is) connected to the Ozarks. For half a century he chronicled his adopted region, writing about its songs, its stories, its folkways, its dialect, its crimes, its peculiaritiesand most importantly its people, without whom those other topics would never have existed. Even now, more than three and a half decades after his death and a quarter century after the last of his posthumous publications, anyone writing anything about the Ozarks has to reckon with Randolph. It would be a stretch to say Vance Randolph defined the Ozarksbut not a great big one. He certainly established the blueprint for analyzing the region and its people, and writers deviating from Randolphs model of the Ozarks and his sketches of the people who encapsulated the Ozark spirit for him must explain their temerity, must account for their foolishness.

I never met Randolph, and I regret that. But I suspect we would not have seen eye to eyewouldnt have geehawed. Looking back on his life from the vantage point of the early twenty-first century, he strikes me as the kind of fellow who puts too much pepper in his beans. And it wouldnt have taken Randolph more than a few moments to peg me as the kind of stiff-necked academician that occasionally quashed his plans and fuzzed up his life from time to time. And he wouldnt have been wrong. Like most scholars, Ive plowed through lifeblinders often securely in placemotivated by a desire to discover the truth, propelled by the belief that lying somewhere in the distance is an accurate rendering of the Ozarker, both historic and contemporary.

Randolph often educated readers about the region and its people, but his primary motivation was entertainment. He knew a good story. He understood that his adopted region shared many characteristics with an increasingly generic American culture but that readers didnt pay money to discover just how similar Carroll County, Arkansas, might be to Delaware County, New York. Anachronism, uniqueness, and regional distinctiveness sold the Ozarks to the American public, and the truth is, theres nothing wrong with that. The Ozark regionthe world, for that matterrelies on both approaches to satisfy lifes yin and yang or its dialectic or however else we humans characterize the often productive union or resolution of seemingly oppositional forces. Randolph may have embellished from time to time and he certainly cherry-picked his informants, but only rarely did he make things up from whole cloth, for the people who best exemplified the Ozarks for him did in fact exist. They may have represented the last of a breedthe evolving world never stops replenishing the supply of that breedbut they were here, and they were bearers of lifeways that were certainly anachronistic, if not completely unique.

Fortunately for the Chronicles of the Ozarks, Bob Cochranlike Randolph an outsider who has now spent most of his life in the regionknew Vance Randolph personally. I consider Bobs excellent 1985 biography of Randolph just as essential to an understanding of the Ozarks as any of the myriad things written by the old codger himself. In spite of his academic credentials, Bob is a character in his own right, not as crusty and irreverent as Randolph, but fully capable of holding his own with the fellow who almost singlehandedly shaped our perceptions of the region. And no one is more qualified to reintroduce us to the book that started it all back in 1931, Vance Randolphs The Ozarks: An American Survival of Primitive Society.

BROOKS BLEVINS

INTRODUCTION

ITS NOT UNUSUAL FOR A debut book in the field to end up as a benchmark in a celebrated authors career, the point where promise blossoms as performance. But even Vance Randolph must have been pleasantly surprised at the success of The Ozarks: An American Survival of Primitive Society. By 1931, when it hit the shelves in late September, the author, who would turn forty at his next birthday, was already an old hand in the writing racket. His first article-length studies of the regions traditional culture had appeared in scholarly journals (Dialect Notes, American Speech, the Journal of American Folklore) in 1926 and 1927, but hed been making money with his pen since the early 1920s by turning out booklets on scientific and psychological topics, mostly for Emanuel Haldeman-Juliuss Little Blue Books series in Girard, Kansas. Life among the Bees and The Psychology of the Affections, both from 1924, are representative titles. Randolph churned these out strictly for the money, received a flat payment with no provision for royalties, and garnered no reviews. The scholarly articles, of course, paid nothing at all, and were read only by small bands of professors and regional culture enthusiasts.

Everything changed with The Ozarks. In the first place, it was a much bigger book, published in hard covers by Vanguard, a left-wing New York firm established in 1926 as a sort of east coast analogue of Haldeman-Juliuss Kansas operation. (Randolph wrote for Vanguard from its beginnings, cranking out such titles as The ABC of Evolution and The Substance of The Descent of Man by Charles Darwin, both from 1926. He turned out a total of six ABC titles, plus two Substance of numbers. All went down without a ripple.)

But The Ozarks made a real splash, earning the new-minted folklore scholar his first national-level reviews in both the literary and the scholarly worlds. The newspapers and literary magazines were quicker on their feet, with well-known novelist and folksong collector Dorothy Scarborough (her On the Trail of Negro Folk-Songs had been issued six years earlier by Harvard) offering up praise in the New York Times Book Review and western history writer Stanley Vestal agreeing more lyrically in the Saturday Review. Both grabbed the hint of Randolphs subtitle, with Scarboroughs review titled Where the Eighteenth Century Lives On, and Vestal citing the volumes appeal for the reader who likes the tang of Shakespearian English or feels nostalgia for that America which passed so swiftly away at the coming of the machine and the immigrant. (Note the immigranthow quickly they forget!)

The scholarly reviews came in more slowly, and not from all quarters. The Ozarks was ignored by the Journal of American Folklore, the field where Randolph would eventually gain his greatest acclaim. American Anthropologist also failed to take note, but Louise Pound and Robert Redfield, prominent figures both, weighed in with applause in American Speech and the American Journal of Sociology

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.