Chronicles OF THE Ozarks

Brooks Blevins, General Editor

OTHER TITLES IN THIS SERIES

Back Yonder:

An Ozark Chronicle

The Ozarks:

An American Survival of Primitive Society

Copyright 2020 by The University of Arkansas Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-1-68226-124-8

eISBN: 978-1-61075-683-9

24 23 22 21 20 5 4 3 2 1

Designed by Liz Lester

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481984.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019949321

SERIES EDITORS PREFACE

As far as I know, Ive only been acquainted with one person who was a confidante of author Catherine Barkerand what an unforgettable person that was. I first met Bess Wolf in the late 1990s. She was already past ninety; I wasnt yet thirty. Bess and her late husband, Quincy, had experienced an Ozarks that I could contact only by listening to their old reel-to-reel tape recordings, reading letters addressed to Quincy from folk singers Almeda Riddle and Jimmy Driftwood, and being swept up in Besss enrapturing stories of backroad journeys, log-house dinners, and front-porch ballads. No one held court quite like Bess Wolf did in her two-story columned house on Boswell Streetthe house that her father-in-law, John Quincy Wolf Sr., had built in Batesville, Arkansas, before her birth.

When I began work on the history of Batesvilles Lyon College (formerly Arkansas College), I found myself back in that inviting home on Boswell Street numerous times, for Bess was one of the schools oldest and most astute alumni, having matriculated when Calvin Coolidge was US president and having been a college staff member in the earliest days of the Great Depression. Her favorite college stories revolved around road trips. She recounted recruiting drives on nearly impassable roads through the Ozarks. She remembered the embarrassment of wheeling the colleges rattletrap automobile down the long, manicured driveway of a wealthy family of benefactors in Hot Springs. As she approached the mansionher hosts watching eagerly from a massive porticothe old car seized, lurched, and rudely dropped its belly pan steps from an ornate flower bed. It proved a stroke of good fortune for the college when the master of the house phoned Batesville and wired enough money to purchase a brand-new automobile.

In the impoverished years that followed the dropped belly pan, Arkansas College would escape seemingly certain death more times than Indiana Jones. Anyone dependent on the struggling institution for a living was in for a bumpy ride, one featuring missed paychecks, curtailed salaries, and even payment in kind. Catherine Barker was one of those people. Wife of an Arkansas College faculty member, Barker survived some of the bleakest years at Batesvilles little school and spent the nations most impoverished years on the southeastern edge of the Ozarks. It was in Batesvilles hinterland hill country that she worked as a New Deal case worker in the early days of Franklin D. Roosevelts presidency. Those experiences inform the book you now hold.

Like her friend Bess Wolf, Catherine Barker had stories to tell about the backroads of the Ozarks and about the people who inhabited them. Unlike Wolfs, Barkers stories were almost devoid of music. That ancient sound of the ballad singer that Bess and Quincy spent years tracking down and recording? For Barker it was simply a murderous nasal twang that ruined many an otherwise good old song. Unlike almost every other writer of her era who had anything to say about the Ozarks, Barker was no romantic.

Maybe it was the sudden exposure to rural poverty at the economic nadir of the cotton-growing Ozarks. Maybe it was all those hand-to-mouth years depending on the sagging fortunes of a seemingly dying college. Maybe she just didnt like the sound of a fiddle. Whatever it was, Barker did not share Vance Randolph and Otto E. Rayburns fascination with celebrating the old ways of the hill country. Seemingly uninterested in folksongs, Jack tales, moonshining, or other pastimes of the ridge-running set, Barker provided an alternative look at the rural Ozarksone perhaps no more objective or free of cultural bias than the romantic portraits of her contemporaries, but a valuable antidote nonetheless.

It seems only fitting that a native of the rural southeastern Ozarks and a graduate of that sturdy little college in Batesville reintroduces twenty-first-century readers to Catherine Barkers Yesterday Today. No one has a deeper understanding of the very real regional poverty about which Barker writes and the unique place this book inhabits in the literature on the Ozarks than does J. Blake Perkins. His excellent introduction is a primer for anyone seeking to understand the cultural politics of chronicling the Ozarks, yesterday and today.

Brooks Blevins

INTRODUCTION

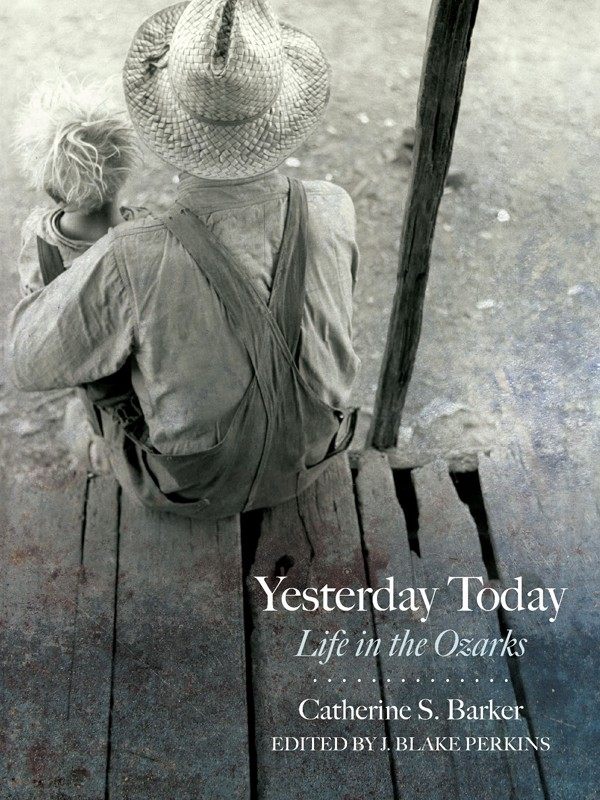

In its review on September 28, 1941, the New York Times described Catherine S. Barkers Yesterday Today: Life in the Ozarks as an extraordinarily interesting book about a little-known backwoods mountain society in Middle America where descendants of pioneers still live according to [their] ancestors ways. Barkers book reflected middle-class Americans interest in the quaint Ozarks mountaineers who lived seemingly simple lives shut off from a world that has passed them by.

Beginning with Vance Randolphs 1931 book The Ozarks: An American Survival of Primitive Society, writers had painted the region as a bucolic landscape inhabited by simple and hardy hill folks whose isolation had left them unspoiled by the superficial trappings of twentieth-century America. Backcountry Ozarkers, according to these romantic tellings, had been insulated in their remote mountain hollers away from mainstream Americas insatiable appetite for progress and modernityan unsustainable craving that some believed may have even caused the country to founder into the Great Depression. Like the Southern Agrarians who penned Ill Take My Stand in 1930, these authors and their readers admired rural Ozarkers exceptional culture and primitive ways of life

But Catherine Barkers Yesterday Today told a very different story than most other Ozarks books published during the period. Her account departed from the romanticism that typified most other Ozarks accounts. Instead, Barker presented a serious-toned telling of the regions deplorable poverty and squalid social conditions. The New York Times reviewer hoped the books realistic grounding in depicting the misfortunes of everyday life in the Ozarks backwoods would deliver a shock to national complacency and a challenge to the need for real progress among men and women who well deserve a better chance. Barker had been a federal social worker in the region in 193334, which she believed gave her an inside track to see the real lives of the isolated mountain folks who lived far away from the regions few hard-surfaced roads and out of sight of the unknowing tourist. She was convinced by what she had seen that there were just as many contemptible facets of old mountain life that needed replaced as there were virtues that needed to be preserved. Barkers compassion for the dirt-poor Ozarks families she had visited and worked to help during the climax of the Great Depression persuaded her that the region was desperate for modern reforms to help rescue poor hill people from their impoverished lives, cultural inertia, and isolation-induced ignorance. We believe, with all its faults, that we have found a better way of life in America, she wrote in

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.481984.