Copyright 2019 by The University of Arkansas Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-1-68226-089-0 (cloth)

ISBN: 978-1-68226-090-6 (paper)

eISBN: 978-1-61075-659-4

23 22 21 20 19 5 4 3 2 1

Designed by Liz Lester

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Phillips, Jared M., 1982 author.

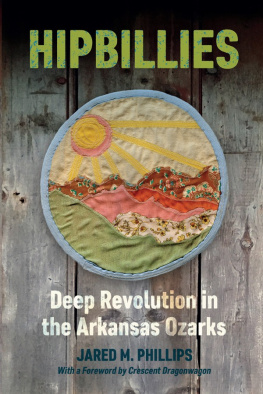

Title: Hipbillies : deep revolution in the Arkansas Ozarks / Jared M. Phillips.

Other titles: Hipbillies, deep revolution in the Arkansas Ozarks

Description: Fayetteville, AR : The University of Arkansas Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2018037826 (print) | LCCN 2018046874 (ebook) | ISBN 9781610756594 (electronic) | ISBN 9781682260890 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781682260906 (pbk. : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Ozark Mountains RegionHistory20th century. | CountercultureArkansasHistory. | CountercultureOzark Mountain RegionHistory. | HippiesArkansasHistory. | HippiesOzark MountainsHistory. | Jeffords, Edd. | Ozark Institute. | ArkansasCivilization. | ArkansasPolitics and government20th century. | Urban-rural migrationUnited StatesHistory. | Self-reliant livingArkansasHistory.

Classification: LCC F417.O9 (ebook) | LCC F417.O9 P55 2019 (print) | DDC 305.5/6807671dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018037826

FOREWORD

I Was a Teenage Hipbilly

As I read an advance manuscript for Jared Phillips Hipbillies, I kept going back to Elvira and the pig creep.

Elvira was a Hampshire sow, black with a white bellyband, on the communal farm I lived on in Ava, Missouri. This was in 1970, back when I was a teenage hipbilly. The pig creep was to be her winter shelter, and I had taken on the task of its construction.

I certainly would have proudly owned the witty self-definition hipbilly had I heard it at the time, but I didnt, not until decades later. We alternative typesand here I must confess that every time I refer to this looser-than-loose affiliation as we, I cringe a littleusually used the word freaks, nonpejoratively, to describe ourselves.

But closer to what I think I considered myself mightve been a fugitive from injustice, in the words of a rock n roll song of the period (What about Me? by Quicksilver Messenger Service). I think a lot of those who were part of the broader back to the land countercultural movement unfolding across the country in that era saw themselves as this kind of fugitive, a point Phillips makes clearly as he takes apart the widespread disgust, horror, and despair, among a certain subset of young people (predominantly white, middle class, educated) when we gazed at our country. We saw an unjust war, systemic racism and injustice, ecologically rash policies, a class-divided consumerist society undergirded by a shortsighted, powerful, threatening military-industrial complex.

Yet, as Phillips points out, we were also disillusioned by its opposition. Taking-it-to-the-streets political action had proved so ineffective at bringing change.

Back to the land represented a third choice. It was a movement that was idealistic, recurrent in America, full of old beliefs about human community and anchored by a renewed belief in the power of the environment (as Phillips puts it). It was contradictory, independent, somewhat hopeful. It promised hard work, meaning, and the chance to live a different life... and maybe save the planet, or a little piece of it.

This movement was not monolithic. Yet there were some universals, and Phillips finds them.

In Hipbillies, I see myselfat least partially. Im here directly, quoted a few times. Im here indirectly, as part of the movement he describes. I was, after all, a Yankee [who] had left the big city and headed for the hills.

That brings me, sort of, to Elvira.

Part of my disgust with the system as a whole was with industrialized food systems that despoiled both human health and the planet. By the time I got to the Ozarks, I was already thinking about food in ways that wound up informing a good chunk of my lifes work: that one should be thoughtful about what one ate, should not be alienated from ones food. If one was going to eat meat, one should accept, up close, slaughter, and should be reverent, holistic, logical, with no disgust at eating organ meat and with no preference for eating some kinds of animals and not others. I am the rare vegetarian who has helped (in her nonvegetarian past) butcher goats, lambs, chickens; who has skinned, cleaned, and eaten squirrel, groundhog, and snapping turtle; and who has prepared and eaten animal livers, kidneys, hearts, brains, and thymus glands (sweetbreads).

In the life I had growing up, far from Ava, Missouri, I had eaten sweetbreads with my father at Sardis, a storied white-tablecloth restaurant in New York Citys theater district, epicenter of my fathers professional world, where he was greeted by name. There, tall men in special black suits with white shirts would lean down asking him, And whos this young lady? And I, in my velvet party dress with the white lace collar, would be introduced.

But what Id learned as the daughter of a show business biographer was of little relevance as a teenager aspiring to self-sufficiency in the Ozarks, except as a source of shame. New York, celebrity: it looked to me then like such irrelevance, decadence, ego, folly, hubris. The world was falling apart, trembling on the brink of ecocide! Who cared if your caricature hung on the wall of Sardis?

Which was how I found myself attempting to build a pig creep in the Ozarks.

I had taken care of Elvira when she was a piglet. We were fond of each other. She would trot over at the sound of my footsteps without even being called and rub her head with its pointed ears affectionately against my knee. Pigs, the man I was then coupled with told me, are as smart as dogs. In contrast to mine, his skill setgrowing up on a farm in Spur, Texaswas useful. He had nothing to be ashamed of. All of us considered him the authority on matters of rural life, though, being antiauthoritarian, none of us would have said so.

When I scratched Elvira behind her ears, she would give a delighted little squeal and push her snout against me, her version of what a dog or cat does when indicating it appreciates the attention and wants more. Still, I was prepared for the fact that one day she would be part of breakfasts and pots of beans.

But black-eyes and bacon would be next fall. Right now it was this fall. Winter was coming. Elvira would need a shelter, called by our Texan a pig creep.

I want to build it, I said. Myself. As much as possible.

For again, there they are, in Phillipss explorations: The currents of feminism and I-can-by-God-do-anything ran through my sensibilities; while Elvira was an actual pig, I was plenty pigheaded and as bristly. I was also an utterly unhandy seventeen-year-old, ashamed of having grown up in a family where you all but called an electrician if you wanted to change a lightbulb. I had to prove that I was of use, now and after the revolution. That I could rely on myself, and my comrades could rely on me, in ways closer to the ground zero of real survival than my velvet-party-dress upbringing.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.