First published 2019

Auckland University Press

University of Auckland

Private Bag 92019

Auckland 1142

New Zealand

www.press.auckland.ac.nz

Jock Phillips, 2019

ISBN 9781776710423

Published with the assistance of Creative New Zealand

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand

This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior permission of the publisher. The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All photos listed without source are by Jock Phillips or from his personal collection.

Book design by Carolyn Lewis

Jacket design by Spencer Levine

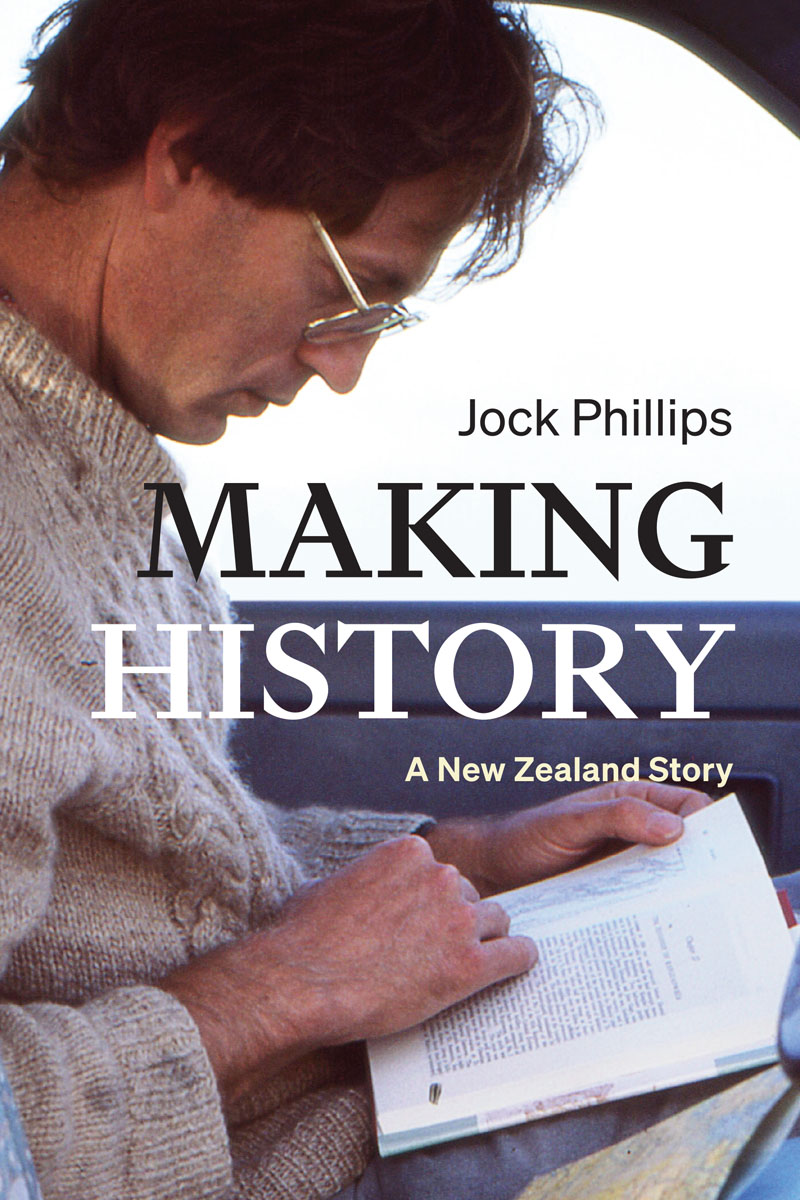

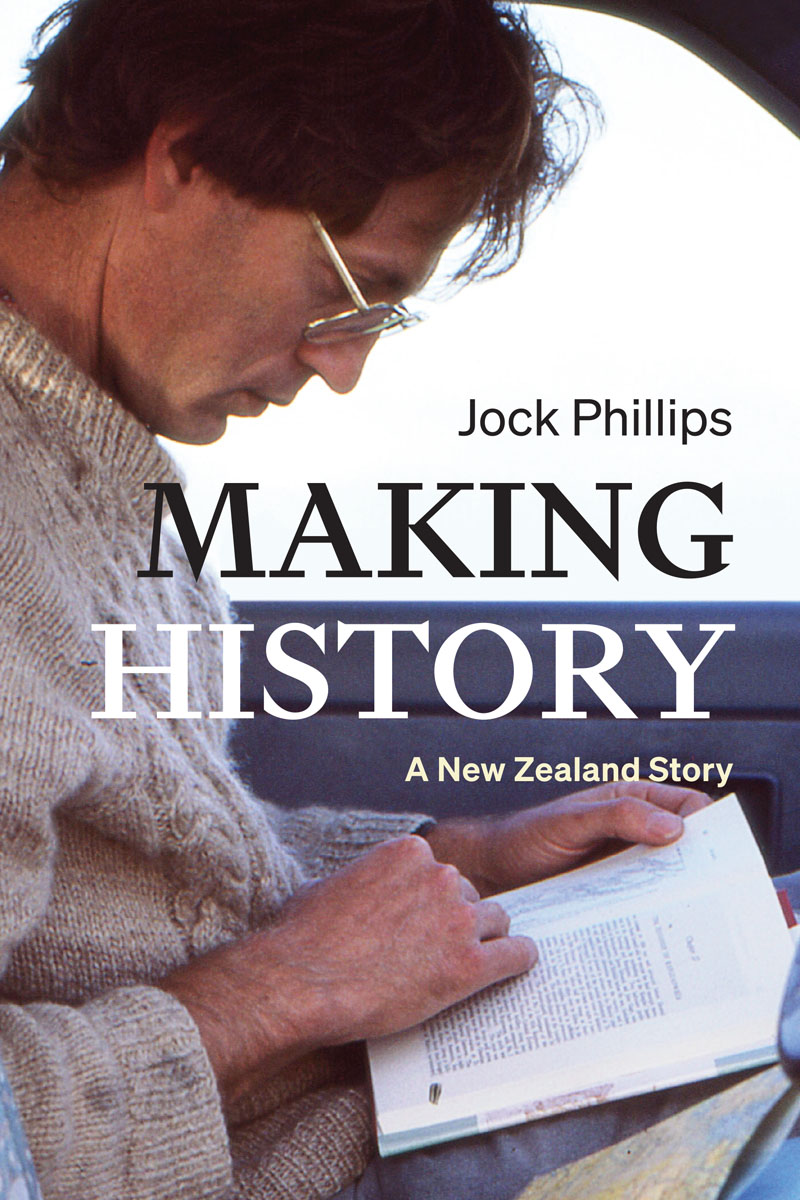

Cover photograph by Chris Maclean

To

Frida Susan Harper,

who has brought love and joy

to my last two decades

Contents

Acknowledgements

This book grew out of a series of well-timed invitations which encouraged me to believe that telling the story of my public-history career might be of wider interest. They came from Doug Monro, who invited me to prepare a chapter for a collection on my father and World War II; from the National Museum of Australia, who requested that I speak about my experiences developing the history exhibitions at Te Papa; from Lydia Wevers and Kerry Taylor, who asked me on two separate occasions to speak about my time at the Stout Research Centre; from the Friends of the Turnbull Library, who honoured me by suggesting I give the Founder Lecture on the journey of developing Te Ara; and from Queens University in Belfast, who invited me to give the Keith Jeffery lecture as a keynote address to a conference on public history about the trials and tribulations of taking history to a broad audience. Without that encouragement this book would never have appeared and would certainly have been longer in the gestation.

In the course of writing the book I accrued other debts. I am grateful to my mother, the late Pauline Phillips, who kept a host of family documents and photographs and also all the letters I wrote to her over thirty years. They proved essential. Jane McCartney also kept the letters I wrote to her from Harvard in 196870 and these were almost too revealing. My two sisters, Elizabeth Caffin and Catherine Phillips, read the text closely and, although neither agreed with every judgement, they forced me to rework matters and each picked up many significant details which needed correcting. My two children, Jesse and Hester, and my stepchildren, Laura, Eve, Julia and Lily, have put up with my absent-mindedness and encouraged me to keep writing. My good friend Chris Maclean, who was writing his own autobiography, was consistently encouraging and urged me on at every opportunity. His close reading of the text greatly improved it; and his photographic documentation of my life made a huge contribution to the images. Geoff Norman also worked his magic on some of the photos. Good friends David Young and David Grant were helpful in the hunt for photographs. Once a full draft was completed, I had really useful comments from Malcolm McKinnon, Ben Schrader and Shaun Barnett. The members of the history reading group to which I belong (Ross Calman, Peter Clayworth, Elizabeth Cox, Mark Derby, Paul Diamond, Emma Jane Kelly, Ewan Morris, Jane Tolerton) gave excellent feedback on the chapter about my father. The readers for Auckland University Press also made crucial suggestions. I owe a special debt to Bronwyn Labrum. Sam Elworthy was enthusiastic at a vital stage and saved me from publishing the book myself; and Caren Wiltons wise and sympathetic editing improved the text greatly. The team at Auckland University Press have done a dedicated, professional job ensuring that my hopes and intentions have been fulfilled. My greatest debt, for her constant encouragement and acute reading of the manuscript, is to my wife, Frida Susan Harper, to whom this book is dedicated.

Introduction

Out of the darkness

The curtains were pulled, the lights went out, the everyday world of school and work and sport began to disappear from consciousness. We were pitched into darkness. And then the projector sprang into life. Images started to appear on the screen of castles and country houses, Roman ruins and Renaissance paintings, the rolling manicured dales of England, all accompanied by the enthusiastic tones of my fathers mellifluous voice. History was coming alive, leaving the humdrum world of Christchurch far behind.

It was 1956. The family was watching coloured slides of my parents journey back to the Old World to the homeland of England and the civilisations of Europe. At last we were looking at a place genuinely old, countries with long and dramatic histories. The situation may have been unusual in the New Zealand of the 1950s, where few people travelled overseas or took coloured slides when they did, but the sentiments were not. Many New Zealanders at that time considered that history was something you encountered overseas. We were a new country, determined to escape the crippling traditions of the old. We had simply not been around long enough to have an exciting, stirring past. The great events, such as wars, coronations and political crises, happened across the other side of the globe. If you wanted history then it was a month heading north in a boat, unless of course you were lucky enough to have a father who took a camera with him.

Those attitudes are now, thankfully, long gone in New Zealand. After years of disinterest many New Zealanders, Pkeh and Mori, began to accept that humans had been in this land for over 700 years, and that Mori had a wonderful storehouse of remarkable people and dramatic events. We began to realise that even in the 200-odd years since Pkeh settlement in the early nineteenth century, New Zealands history was packed with fascinating individuals and compelling stories. Slowly we started to invest our country with history institutions like the Historic Places Trust (now Heritage New Zealand) and the Waitangi Tribunal emerged to explore and make judgements about our past; historic markers and new memorials appeared on roadsides; historians such as Keith Sinclair, Judith Binney, James Belich, Michael King and Claudia Orange were widely read; historical novels were written and television series were made about our history. Some New Zealanders even came to accept that important battles in a major civil war had taken place on the soil of this land.

This awakening of New Zealanders to their history is one of the great revolutions of my lifetime. It has been my privilege to both exemplify the change and be an actor in the story. As a child I thought of history as a kind of romantic dream which took place across the seas or in special slide-shows at home. History did not inhabit my day-to-day world. By my late twenties I had come to believe that for all countries, old and new, the past was an important path to understanding the present, and in New Zealands case we had a fascinating multi-layered history that was central to our evolving set of identities. I felt it was a major social obligation to enrich New Zealanders understanding of their past. While I grew up with a family background and training in academic history, a discipline which I still admire, I began, unwittingly at first, to learn how to use new techniques to talk to a wider audience than just students in the front row of my lectures or the few specialists perusing a scholarly journal. I became a public historian of New Zealand, communicating to a more general non-academic audience, and I stumbled on new techniques to make this possible a popular style of writing, the use of images, working on museum exhibitions, talking on radio and television, developing new languages of history for the web.

Next page