This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.indiana.edu

Telephone orders 800-842-6796

Fax orders 812-855-7931

2013 by Jeffrey Veidlinger

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Veidlinger, Jeffrey, 1971 author.

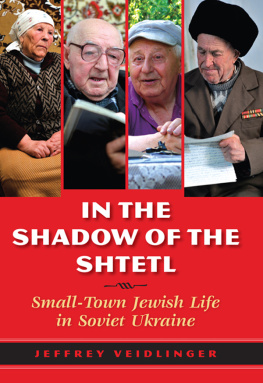

In the shadow of the shtetl : small-town Jewish life in Soviet Ukraine / Jeffrey Veidlinger.

pages ; cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-253-01151-0 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-253-01152-7 (ebook) 1. ShtetlsUkraineHistory20th century. 2. ShtetlsUkraineVinnytska oblast History20th century. 3. JewsUkraineSocial life and customs20th century. 4. JewsUkraineVinnytska oblastSocial life and customs20th century. I. Title.

DS135.U4V45 2013

305.892404778dc23

2013014359

1 2 3 4 5 18 17 16 15 14 13

For those who shared their stories with us.

Memory

Longing

Has many faces

Many faces and expressions

And each and every one of them

Surprises and suppresses.

But you,

You collect faces,

Safekeeping their tone and timbre,

So that nobody

Will ever

Quarrel again

With memory.

BORIS KARLOFF

INTRODUCTION

When I first started searching for Jewish life in the small towns of Eastern Europe, the shtetls of Yiddish lore, I thought I would find only cemeteries and dilapidated homes, lifeless remnants of a vanished community. Instead, over the last decade, in dozens of shtetls throughout Eastern Europe, I have taken part in oral history interviews with nearly four hundred Yiddish-speakers, who have shared their memories of Jewish life in the prewar shtetl, their stories of survival during the Holocaust, and their experiences of living as Jews under communism. This book recounts some of their stories.

The story of how the Holocaust decimated Jewish life in the small towns, the shtetls, of Eastern Europe is well known. But it is a story that has been told exclusively by those who leftfor America, Israel, or the major cities of the Russian interiorduring or immediately after the war. These writers long assumed that nothing remained of the shtetls they abandoned; they variously portray their hometowns as lost, vanished or erased. Their continued existence, and the way their residents remember the last century, complicates the traditional narrative of twentieth-century Jewish history.

The assimilated Soviet Jewish intelligentsia based primarily in Moscow and St. Petersburg, and occasionally in Odessa or Kiev, has come to define Soviet Jewry for the world. Jewish collective memory has imagined the shtetl as a foil, or simply a wellspring from which Jewish modernity emerged. The Jewish cobblers, market-stall proprietors, barbers, and collective farmers who remained in the small towns and rural areas of Eastern Europe until the dawn of the twenty-first century were conveniently forgotten; they did not conform to the nostalgic image of the shtetl with its simple and pious way of life that inspired numerous works of literary fiction, Broadway plays, Hollywood films, and academic scholarship.

This study follows the lives of a cohort of individuals, all of whom were reared in the shtetls during the early years of the Soviet Union and were just starting out their adult lives when the world as they knew it was shaken and eventually destroyed with the Nazi invasion. The oldest were born in the midst of the First World War and the violence of the to victory were derided as cowards and were accused of having fought on the Tashkent front, where many had fled in evacuation. Some Jews turned toward their religion for solace and comfort, but found that a new state policy of antisemitism discriminated against them professionally and against Judaism spiritually. Most married, had children, and later grandchildren, which brought joy and love into their lives. But today the Jews who remained tend to live far away from their beloved progeny, many of whom emigrated to Israel, America, Germany, or the large cities of Russia. The postwar era in general gave Jews few rewards for the sufferings they had endured. It is no wonder, then, that when asked to pinpoint the best times of their lives, many of the people we interviewed simply cried and shook their heads.

This book explores the experiences of some of the last Jewish residents of Eastern European shtetls, those who reside in the small towns of Vinnytsya Province, which includes, in addition to the regional capital Vinnytsya, the towns of Bershad, Bratslav, Mohyliv-Podilskyy (Mogilev Podolsk), Sharhorod (Shargorod), Teplyk (Teplik), Tomashpil (Tomashpol), and Tulchyn (Tulchin), as well as several smaller communities. At the same time, local party officials were forced to reckon with deep-held religious beliefs, Zionist aspirations, and endemic poverty in the surrounding towns before they could remake society in the image of Marx and Lenin. The Revolution here moved at the speed of evolution.

Ukraine

Although the focus of this book is on the shtetls of Vinnytsya Province, I also draw from several larger cities, such as Berdichev and Uman, which are neither shtetls nor within the borders of Vinnytsya Province. Uman is situated across the current eastern border of Vinnytsya in Cherkasy Province and was located in Kiev Province under the tsars. Berdichev, in contrast, is just across the current northern border of Vinnytsya in Zhytomyr Province. It too fell within Kiev Province in tsarist times. These cities figured very much within the real world of the Jews of that region, the boundaries of which extended beyond the hills and rivers immediately surrounding their own shtetls. Jews from Vinnytsya Province travelled to these larger cities for multiple purposeswork, trade, school, family visits, and religious pilgrimages. These larger urban centers also had significant Jewish populations, and continue to host sizable Jewish communities.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.