The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

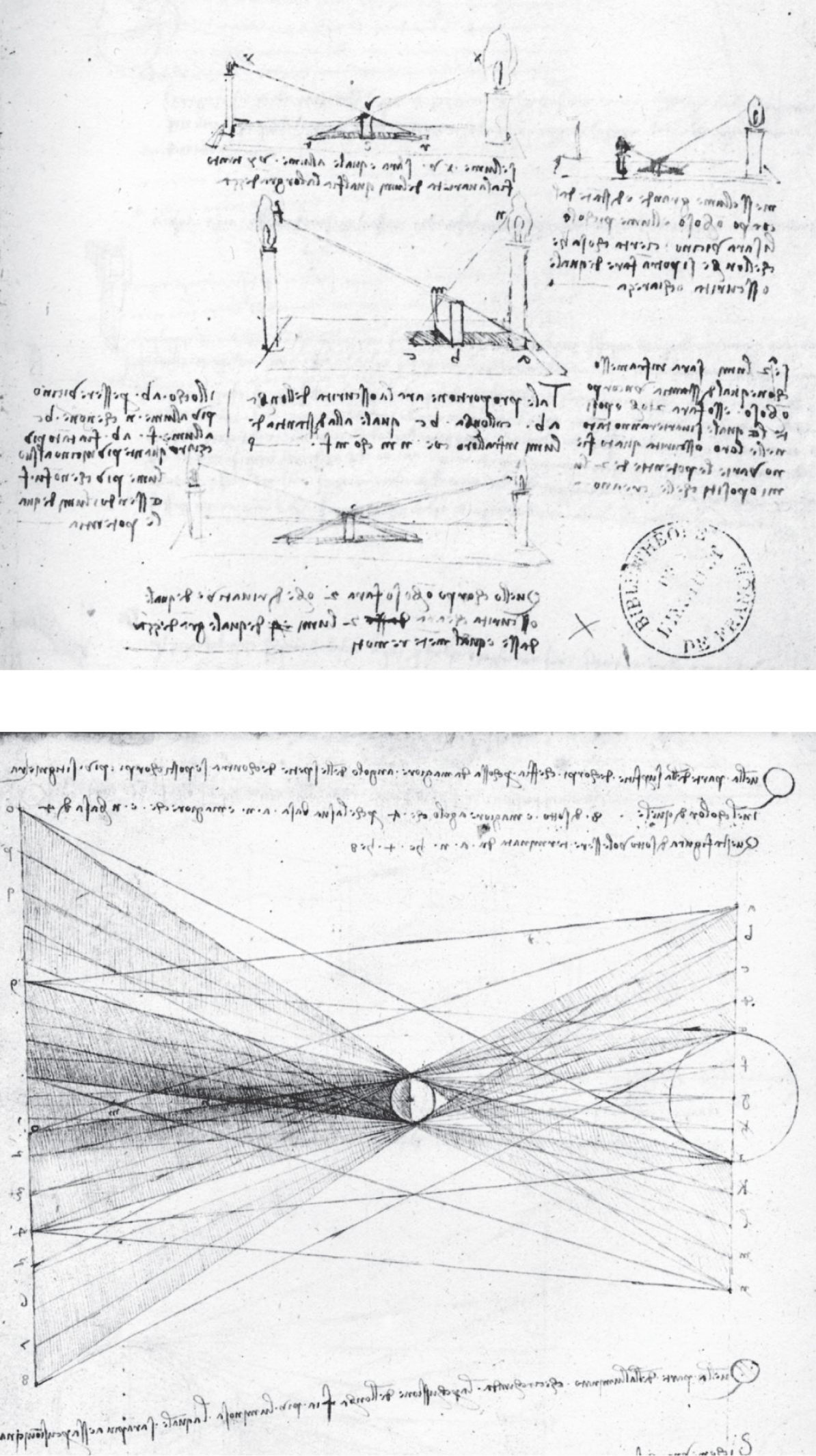

We know why the candle was on Leonardos deskto bring light into the darkness. But why a ball and a small screen, perhaps made of thick paper, or of simple wood?

The shadow drawings suggest an answer.

When darkness fell and there was no other source of light in the room, Leonardo lit the candle and lined up the threecandle, ball, and screen. The small portion of the balls surface that directly faced the candle was brightly lit. But, moving outward in any direction, he could see that the remainder of the ball was left in varying degrees of shadow, as if the light never quite came its way. Where, then, did that light go instead?

Depicting the light not as we see itas one solid beambut rather as a set of discrete rays, he charted the individual destination of each and every one, line by line. Clearly, he knew something about the science of opticsor at least how light behaves when it hits an opaque objectbecause with exquisite precision he identified which rays would hit the ball in a straight line and be reflected straight back to the viewer (providing that brightness) and which, because of a more acute angle of incident (or impact), would hit it diagonally, leaving the edges of the ball in deeper and deeper shadow.

Again and again, he repeated the experiment, moving the ball closer to the light and then farther away, sometimes to the left and then to the right. He added a second source of light and examined the effect as the light from one source intersected with the light from the other. And he looked at the color of the ball and saw that it changed just as the shadows and light changed. And then there came the day he moved outside, ready to tackle the most difficult question of allhow the rays of the sun behave when they, too, meet an opaque object, such as a ball. Or, one must imagine, a human form.

For nothing was more important to him than the rules of optics, as one of his contemporaries noted. But in fact this obsession appears to have been very narrowly focused on just one aspect of optics: when and where light produces shadow. Every one of his notes beneath these sketches makes this point:

Every shadow made by an opaque body smaller than the source of light casts derivative shadows tinged by the color of their original shadow.

An opaque body will make two derivative shadows of equal darkness.

Just as the thing touched by a greater mass of luminous rays becomes brighter, so that will become darker which is struck by a greater mass of shadow rays.

Why this obsession with shadows? Because of some new invention or experiment he was considering? No. His goal was a different one: to learn how to paint.

As a young boy, when he was taken by his father to apprentice at the most important bottega (or workshop) of the early Renaissance, Leonardo had learned how to draw. Given a piece of charcoal or a quill pen dipped in ink, he could sketch a complex set of figures striking poses that were simultaneously true to life and emotionally evocative. Not surprisingly, while other new apprentices were sent to wash brushes or work on the mass-produced objects meant for the middle class, Leonardo quickly joined his master, Andrea del Verrocchio, at the easel, where the most important work of the bottega was donethe paintings meant for the Church or other important patrons.

But that same young man who could draw almost anything had yet to learn how to paint. And by how to paint, I am not referring to how to mix colors or apply them to the panel. I am referring to the sensibility of an artist who instinctively reaches for what makes a painting a great painting.

At the time, a quiet revolution was just starting to take hold in the world of Renaissance art, especially in the bottega of Verrocchio, one that would be based upon a new kind of revelation. This revolution was not the sort achieved through faith, which is what the Church wanted its paintings to convey. Nor would it be based upon the fixed truths rulers expected artists to use their talents to reinforcethat each of us must know our place in the larger scheme of things, deferring to the supposedly inherent nobility of those above us. Rather, this revolution in art was founded on the notion that a new and different kind of truth was waiting to be identified by our senses and made sense of by our mindsthe truth that came from careful observation.

Just how this revolution would lead Leonardo to a new kind of artone that would move viewers much more deeply, and one that speaks to us today in a way that most Renaissance painting does notis the story this book tells. Crucial to that story, however, is the unraveling of a mytha myth propagated, as my book will explain, by a renowned authority in the decades after his death. I am referring to the notion of Leonardo as the iconic representative of two very different forms of genius.

Leonardo, it is commonly believed, is the artist who painted masterpieces such as the Ginevra de Benci, the Mona Lisa, and the Last Supper and drew the iconic Vitruvian Man and then underwent a metamorphosis of sorts. Somewhere in his late thirties and early forties, there is the emergence of a second Leonardo, the one who imagined inventions that would not come to exist until centuries later, from the parachute to the flying machinethe one who became fascinated by science and philosophy.

The artist and the scientist. Each exceptional in his own way, but representing different parts of the same man. The traditional characterization of this dual Leonardo is that the natural philosopher in him decided to work out scientifically what the artist had somehow vaguely intuited decades earlier.

Many of us who inadvertently helped perpetuate this dual-genius thesis had good reason to do so: scholars relied, after all, on documents Leonardo himself left us, in particular his folios, or notebooks. Many of the folios are dated, and based on those dates (with the exception of a few outliers, which were somehow ignored), it seemed that the vast majority of his shadow drawings, for instance, were done when Leonardo was well into his late thirties or early fortiesin other words, long after he knew how to paint, and contemporaneous with his shift toward his philosophical investigation of nature. Science was called natural philosophy back then.

But do the dates written on the folios indicate what we have long assumed they indicate?

Let me explain.

It always surprises my students when I tell them that Leonardo was one of the least prolific painters of his time. Over a period of about four decades, he left us only between twelve and fifteen paintings (the number changes depending on the attribution of a handful of controversial works), and a number of these he never fully completed, including, it might surprise many to learn, the