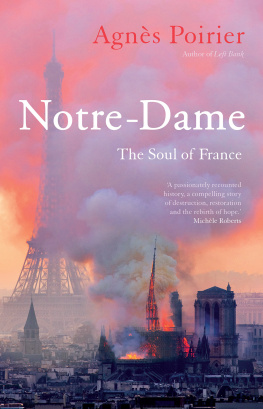

Also by Agns Poirier

Touch: A Frenchwomans Take on the English

Left Bank: Art, Passion and the Rebirth of Paris 194050

I have never felt anything like this before [...]

I have never seen anything so movingly serious and sombre.

Sigmund Freud, in a letter to his fiance, Martha,

19 November 1885

It is not enough to look at Notre-Dame, one must live it.

At length. Daily. She would not be, for us, Gods servant,

if she was not of any use to us too.

Paul Claudel, 1951

To Ma Dame ,

Garance

Contents

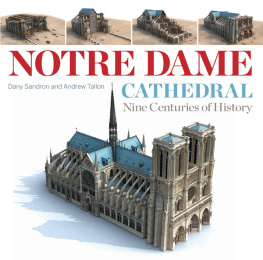

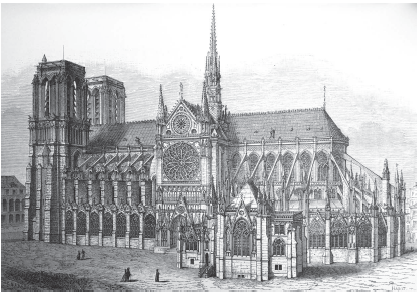

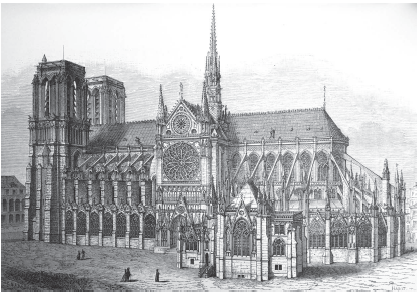

Lateral view of Notre-Dame, after an engraving by M. Baldus.

Prologue

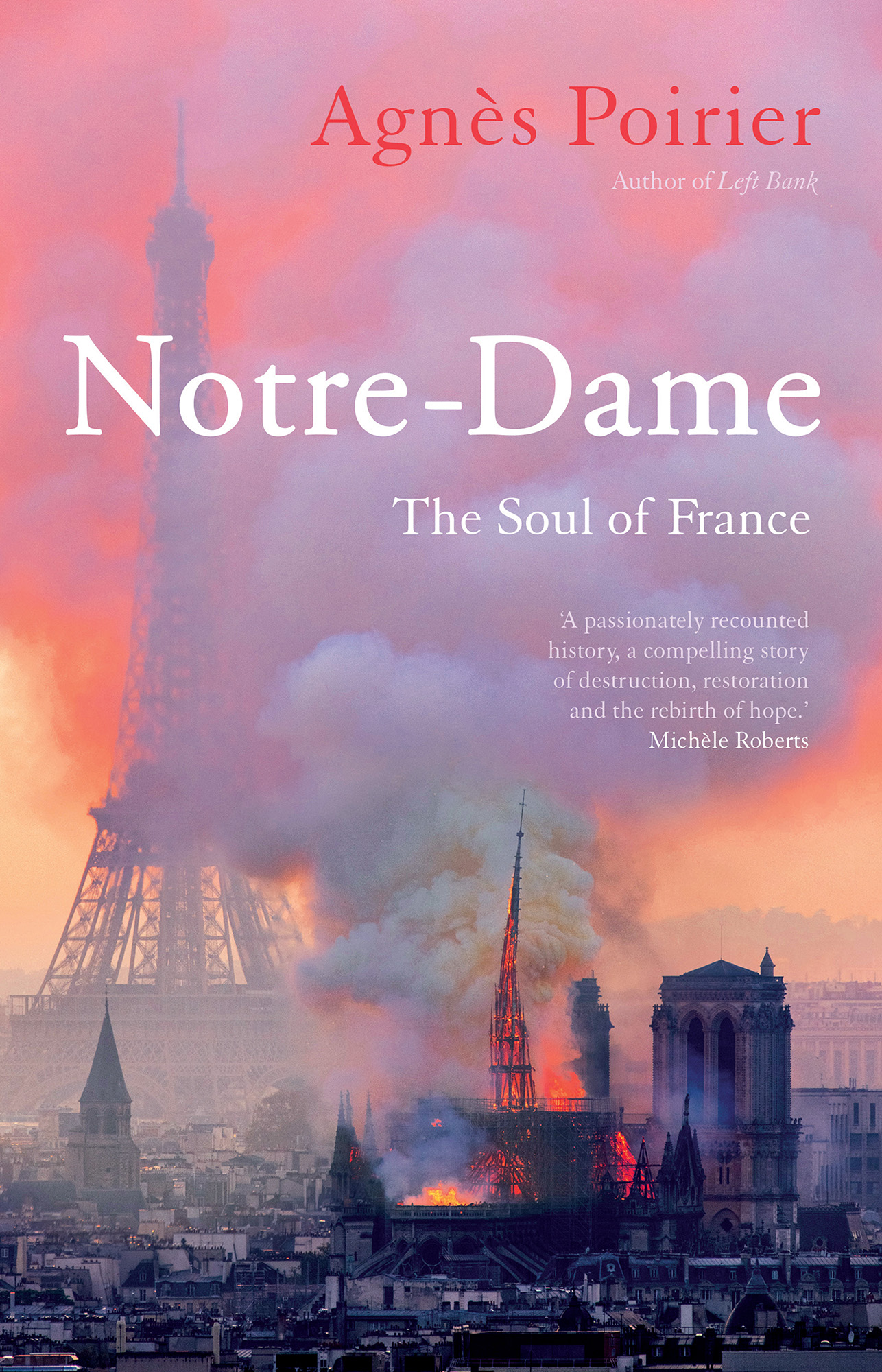

Of the night of the fire I remember a kaleidoscope of images, a collision of emotions, in quick succession. Seeing bright-yellow plumes of smoke through my kitchen window coiling into the sky, then rushing down the stairs onto quai de la Tournelle, standing right opposite Notre-Dames south rose window, the red and orange tongues of fire leaping from the roof, the resounding silence of the crowd, the stunned look in peoples eyes, the horrific beauty of the moment, tears pearling on cheeks, lips forming silent prayers, the precise, focused actions of fire-fighters as if suddenly transformed into field surgeons, fire hoses appearing at every corner like giant serpents, the flaming torch of the spire about to collapse, the pink-hued medieval stones against a royal-blue sky, then the black smoke rising from the north tower, and the unbearable realization and excruciating thought: Our Lady might go.

We need certainties: they are the framework of our existence, the signposts without which we cant navigate life, let alone endure its many tests and trials; for 850 years Notre-Dame was one such. Those of us who had forgotten received a shocking reminder on the night of 15 April 2019. If Notre-Dame could crumble in front of our eyes and disappear from our lives, so too could those other certainties democracy, peace and fraternity. The head teachers of Paris, who summoned psychologists to assist in primary schools the morning after, understood this perfectly. Many children brought with them little plastic bags filled with fragments of blackened timber that they had picked up from balconies and pavements. Their parents had told them that those tiny bits of charcoal dated back to the Crusades, and they now needed to be comforted with the thought that nothing irreparable had taken place. Reassuring the children was easier than reassuring ourselves.

That evening, as the first images of the tragedy started flooding onto social networks and TV screens, a wave of emotion almost immediately surged towards the tiny island of le de la Cit in Paris, the cradle of France, from every corner of the world. We Parisians felt, as often in history, at one with the world, united in a harmony of grief.

Why were we all feeling so traumatized?

Notre-Dame has always been far more than just a cathedral, a place of worship for Catholics and a beautiful monument whose stained glass dates back to the thirteenth century. Notre-Dame is one of mankinds greatest architectural achievements, the face of civilization and the soul of a nation. Both sacred and secular, Gothic and revolutionary, medieval and romantic, she has always offered a place of communion and refuge to everyone, whether believers or atheists, Christians or otherwise.

Victor Hugo and his hunchback transformed Notre-Dame into a world heroine and saved her from the dire neglect into which she had fallen 200 years ago. She rose again in the 1860s, in neo-medieval magnificence, thanks to the architect Eugne Viollet-le-Duc, a scholar of medieval art who reinvented Notre-Dame and gave her a spire with which she could have been born. Through the new art forms of photography and cinema she became a universal icon, a character of flesh and blood in the worlds imagination, alongside Quasimodo, Esmeralda and the monstrous but endearing gargoyles adorning her faade. In this way a love of Notre-Dame, this living being of a Gothic cathedral, has passed from one generation to the next.

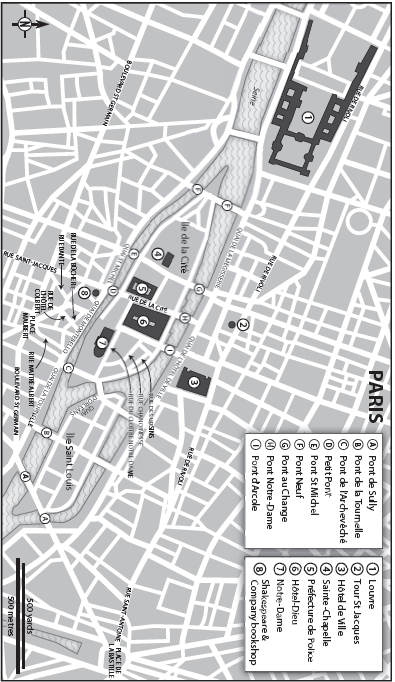

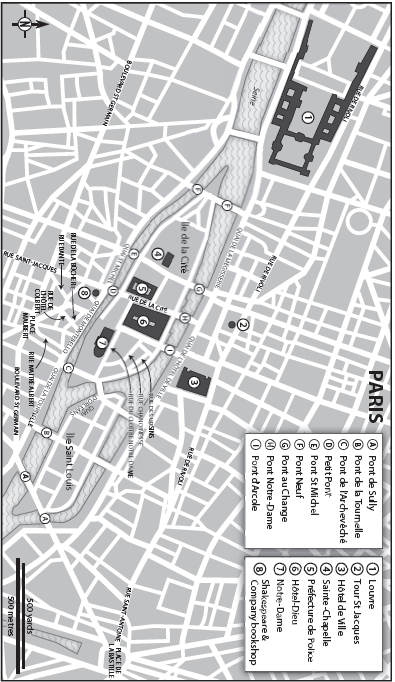

Her mesmerizing beauty also made the possibility of her demise all the more inconceivable. Built and rebuilt over ten centuries, a constant work of perfection in progress, Notre-Dames loveliness is both unique and multi-faceted. Everyone has their favourite view of the cathedral. For some it is the view from pont de lArchevch, as one walks from the Left Bank towards the garden lying in the shadows of her flying buttresses, or slightly further to the east, from the middle of pont de la Tournelle, where the cathedral rises like the majestic prow of a ship called France . For others it is from quai dOrlans on Pariss twin island, le Saint-Louis, where she suddenly appears at the curve of the leafy embankment, or perhaps simply from the middle of the parvis the square in front of the main doors of the cathedral, the west rose window and twin towers in all their glory. For others still it is from quai Montebello and the terrace of the Shakespeare & Company bookshop.

Pablo Picasso liked the view from the garden at the back. On 15 May 1945, the bull-fighting enthusiast asked the photographer Brassa: Have you ever photographed Notre-Dame from behind? I quite like Viollet-le-Ducs spire. It looks like a banderilla sticking out of her back!

My own favourite is from the corner of rue de la Bcherie and rue de lHtel Colbert, below quai de Montebello, at the bottom of three medieval steps, right next to the building where in October 1948 Simone de Beauvoir rented a tiny attic room with a view of the spire. At street level this narrow glimpse of Notre-Dame keeps you guessing and wanting to see more, and infallibly draws you towards her.

Notre-Dames beauty is of a kind one never takes for granted; it is a constantly renewed miracle, which stuns you each time you meet her gaze. The secret of her loveliness lies in a powerful combination of familiarity and nobility, both warm and grandiose. How can a monument be so intimate and so imposing at the same time?

To dive into Notre-Dames past is to immerse oneself in the soul of France, a history full of glory, torment and contradictions. In the last 850 years, Notre-Dame has witnessed the best of France and the worst of France. On 15 April 2019 she almost died as a result of human carelessness and was only saved in extremis by the courage of those ready to sacrifice their lives for her.

*

Notre-Dame: The Soul of France pays tribute to Maurice de Sully, the peasants son who became bishop of Paris and oversaw the initial construction of the cathedral in the late twelfth century; and it features Henri IV, who, realizing that he couldnt govern against Paris, converted to Catholicism, paid his respects to Notre-Dame and reconciled a country deeply divided by thirty years of war between Protestants and Catholics. Henris son, Louis XIII, consecrated his crown and Frances fortune to the Virgin Mary at Notre-Dame, and his own son, Louis XIV, the Sun King, fulfilled his fathers vow.

In 1789 and through Robespierres Terror, the shrewd cathedral organist played revolutionary songs and the Marseillaise instead of religious hymns, and an equally astute canon decided to safeguard the statues of the Sun King and his father, leaving the Virgin Mary to fend for herself alone before stern atheists and staunch republicans. He did well: they only dared remove her golden crown. The twenty-eight kings of the faades upper gallery were less fortunate: each of them lost his head. Napoleon restored Notre-Dame, which had been rededicated as a temple of reason during the revolution, to her original faith. By choosing to be crowned emperor there in 1804 he also placed her at the centre of Frances public and political life, paving the way for Victor Hugo and his hunchback.