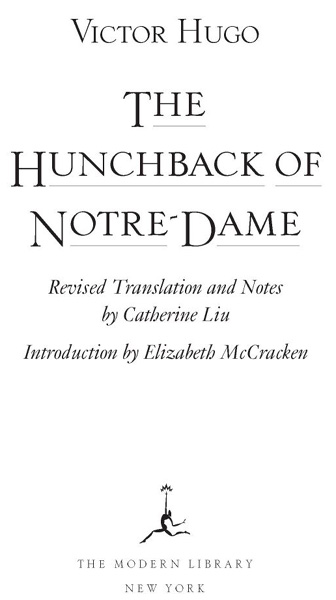

Victor Hugo - The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

Here you can read online Victor Hugo - The Hunchback of Notre-Dame full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2007, publisher: Random House Publishing Group, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

- Author:

- Publisher:Random House Publishing Group

- Genre:

- Year:2007

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Hunchback of Notre-Dame" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Hunchback of Notre-Dame" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Table of Contents

VICTOR HUGO

Victor-Marie Hugo was born in 1802 in Besanon, where his father, an officer (eventually a general) under Napoleon, was stationed. In his first decade the family moved from post to post: Corsica, Elba, Paris, Naples, Madrid. After his parents separated in 1812, Hugo lived in Paris with his mother and brothers. His literary ambitionto be Chateaubriand or nothingwas evident from an early age, and by seventeen he had founded a literary magazine with his brother. At twenty he married Adle Foucher and published his first poetry collection, which earned him a small stipend from Louis XVIII. A first novel, Han of Iceland (1823), won another stipend.

Hugo became friends with Charles Nodier, a leader of the Romantics, and with the critic Ste.-Beuve, and rapidly put himself at the forefront of literary trends. His innovative early poetry helped open up the relatively constricted traditions of French versification, and his playsespecially Cromwell, whose preface served as a manifesto of Romanticism, and Hernani, whose premiere was as stormy as that of Stravinskys Rite of Springstirred up much protest for their break with dramatic convention. His literary outpouring between 1826 and 1843 encompassed eight volumes of poetry; four novels, including The Last Day of a Condemned Man (1829) and Notre-Damede Paris (1831); ten plays (among them Le Roi samuse, the source for Verdis Rigoletto); and a variety of critical writings.

Hugo was elected to the Acadmie Franaise in 1841. The accidental death two years later of his eldest daughter and her husband devastated him and marked the end of his first literary period. By then politics had become central to his life. Though he was a Royalist in his youth, his views became increasingly liberal after the July revolution of 1830: Freedom in art, freedom in society, there is the double goal. Following the revolution of 1848, he was elected as a Republican to the National Assembly, where he campaigned for universal suffrage and free education and against the death penalty. He initially supported the political ascent of Louis Napoleon but turned against him when Louis-Napoleon established a right-wing dictatorship.

After opposing the coup dtat of 1851, Hugo went into exile in Brussels and Jersey, launching fierce literary attacks on the Second Empire in Napoleon the Little, Chastisements, and The Story of a Crime. Between 1855 and 1870 he lived in Guernsey in the Channel Islands. There he was joined by his family, some friends, and his mistress, Juliette Drouet, whom he had known since 1833, when as a young actress she had starred in his Lucrezia Borgia. His political interests were supplemented by other concerns. From around 1853 he became absorbed in experiments with spiritualism and table tapping. In his later years he wrote The Contemplations (1856), considered the peak of his lyric accomplishment, and a number of more elaborate poetic cycles derived from his theories about spirituality and history: the immense The Legend of the Centuries(18591883) and its posthumously published successors, The End of Satan (1886) and God (1891). In these same years he produced the novels Les Misrables (1862), Toilers ofthe Sea (1866), The Man Who Laughs (1869), and Ninety-three (1873).

After the fall of the Second Empire in 1870, Hugo returned to France and was reelected to the National Assembly, and then to the Senate. He had become a legendary figure and national icon, a presence so dominating that on his death in 1885 mile Zola is said to have remarked with some relief: I thought he was going to bury us all! Hugos funeral provided the occasion for a grandiose ceremony. His body, after lying in state under the Arc de Triomphe, was carried by torchlightaccording to his own request, on a paupers hearse to be buried in the Panthon.

AUTHORS PREFACE

A few years ago, when the author of this book was visiting or, better yet, rummaging around Notre-Dame, he discovered in an obscure corner of one of the towers this word, carved into the wall by hand:

ANKH1

These capital letters in Greek blackened by age were deeply engraved in stone with I am not sure what marks that belong to Gothic calligraphy imprinted in their forms and shapes, as if to reveal that it was a hand from the Middle Ages that had written them there. Above all, the author was struck by the ominous and fatal feeling emanating from this writing. He wondered, and tried to guess, what kind of tortured soul would not want to depart this world without leaving behind this stigmata of either crime or unhappiness on the brow of an old church.

Since then, there has been some whitewashing or scraping (I do not know which) of the wall, and the inscription has disappeared. For a hundred years now, this is what we do with the marvelous medieval churches. They are mutilated from all sides, from within and without. The priest whitewashes, the architect scrapes, and then the people show up and demolish them.

Therefore, except for the fragile memory to which the author dedicates this book, there exists no other trace of this mysterious word inscribed in a dark tower of Notre-Dame. Nothing else remains of the unknowable fate that this word summarized so tragically. The man who wrote this word on the wall disappeared many centuries ago, the word in its turn has disappeared from the wall of the church, the church itself will perhaps soon disappear from the face of the earth.

It was upon this word that this book was written.

TRANSLATORS PREFACE

Catherine Liu

By updating and revising the Modern Librarys anonymous translation of Victor Hugos Notre-Dame de Paris, I have made the novel more accessible to a contemporary audience, but I have also made the original translation with all its mistakes and prejudices disappear. There are two major changes that have been made. The original translation was hasty and prudish to the extreme. Not only were descriptions of La Esmeraldas heaving bosom and graceful legs simply dropped, Claude Frollos erotic obsession and sadism were veiled in Anglo-Saxon euphemisms that Hugo would have ridiculed. The novel is much more sensual, much earthier, and much more troubling when this erotic language is restored to Hugos portrait of unreciprocated love, for not only is Claude Frollo more monstrous, La Esmeraldas own orgasmic swoon and her inability to give up her Captain make her less innocent than most English readers have believed her to be. Contemporary readers will be more shocked by Hugos obvious prejudices against gypsies, Jews, and other ethnic and religious European minorities. Hugos use of the term Egyptian for gypsy betrays the Western European geography: decadence, paganism, and nomadism originate in the East. I have dropped Egyptian in favor of gypsy, but the usage is an example of nineteenth-century Orientalism and the fantasy of an East that was both reviled and desired.

Most English readers think of the Hunchback as the protagonist of the novel: this is probably due to the fact that the French title, Notre-Dame de Paris, has been translated as TheHunchback of Notre-Dame. Architecture is the real hero of the novel. Hugos descriptions of Parisian places and palaces, and his account of the history of the city, are impassioned, awkward, and monstrously overburdened, like the Cathedral itself, with details. Architectural archaeology becomes the most important structuring theme of the novel. The original translator left out two crucial chapters that he or she must have believed to have not been important to the plot. These two chapters, which are included here in Book V, are Abbas Beati Martini and This Will Kill That. The first is about the alchemical formulae that are thought to be inscribed upon the portals of the Cathedral of Notre-Dame, the second about the displacement of architecture as the most important aesthetic and cultural enterprise of pre-Modern Europe by the book, whose dissemination and reproduction was made possible by the invention of the printing press and movable type. Hugo makes the wonderful argument that the book will kill the building because, in the time of the Cathedrals construction, architecture was the highest cultural achievement and people gave to it all of their energies. Not only was architecture celebratory of the Christian deity, it preserved all sorts of heretical and mystical knowledge. Hugo predicts that with the invention of the printing press by Gutenberg, the energies formerly channeled into architecture would go into the production of books. The age of great Gothic architecture is over: all subsequent styles are ridiculous to Hugo, for whom the soaring, impossible lines of Notre-Dame de Paris incarnate in stone the impassioned aspirations of generations of craftsmen and architects.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Hunchback of Notre-Dame»

Look at similar books to The Hunchback of Notre-Dame. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Hunchback of Notre-Dame and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.