Table of Contents

From the Pages of

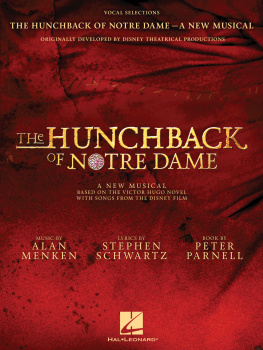

The Hunchback of Notre Dame

Upon this barrow rode resplendent, with crosier, cope, and miter, the new Pope of Fools, the bell-ringer of Notre-Dame, Quasimodo the Hunchback. (page 66)

The trunk of the tree is fixed; the foliage is variable. (page 111)

Say if you know of anything on earth richer, more joyous, more mellow, more enchanting than this tumult of bells and chimes; than this furnace of music; than these ten thousand brazen voices singing together through stone flutes three hundred feet in length; than this city which is but an orchestra; than this symphony which roars like a tempest. (page 134)

This foundling, as they call it, is a regular monster of abomination. (page 136)

The poor little imp had a wart over his left eye, his head was buried between his shoulders, his spine was curved, his breastbone prominent, his legs crooked; but he seemed lively; and although it was impossible to say in what language he babbled, his cries proclaimed a certain amount of health and vigor. (page 142)

It was Quasimodo, bound, corded, tied, garotted, and well guarded. The squad of men who had him in charge were assisted by the captain of the watch in person, wearing the arms of France embroidered on his breast, and the city arms on his back. (page 188)

Come and see, gentlemen and ladies! They are going straightway to flog Master Quasimodo, the bell-ringer of my brother the archdeacon of Josas, a strange specimen of Oriental architecture, with a dome for his back and twisted columns for legs. (page 219)

The people, particularly in the Middle Ages, were to society what the child is to a family. So long as they remain in their primitive condition of ignorance, of moral and intellectual nonage, it may be said of that as of a child,

It is an age without pity.

(pages 220-221)

A man must live; and the finest Alexandrine verses are not such good eating as a bit of Brie cheese. (page 244)

The cathedral seemed somber, and given over to silence; for festivals and funerals there was still the simple tolling, dry and bare, such as the ritual required, and nothing more; of the double noise which a church sends forth, from its organ within and its bells without, only the organ remained. It seemed as if there were no musician left in the belfry towers. (pages 249-250)

Lovers talk is very commonplace. It is a perpetual I love you. A very bare and very insipid phrase to an indifferent ear, unless adorned with a few grace-notes; but Claude was not an indifferent listener. (page 283)

It was but too truly Esmeralda. Upon this last round of the ladder of opprobrium and misfortune she was still beautiful; her large black eyes looked larger than ever from the thinness of her cheeks; her livid profile was pure and sublime. (page 333)

A drop of water and a little pity are more than my whole life can ever repay. (page 357)

The heart of man cannot long remain at any extreme. (page 357)

Fate has delivered us over to each other. Your life is in my hands; my soul rests in yours. Beyond this place and this night all is dark.

(page 452)

Victor Hugo

Novelist, poet, dramatist, essayist, idealist politician, and leader of the French Romantic movement from 1830 on, Victor-Marie Hugo was born the youngest of three sons in Besanon, France, on February 26, 1802. Victors early childhood was turbulent: His father, Joseph-Lopold, traveled frequently as a general in Napoleon Bonapartes army, forcing the family to move throughout France, Italy, and Spain. Weary of this upheaval, Hugos wife, Sophie, separated from her husband and settled with her three sons in Paris. Victors brilliance declared itself early in the form of illustrations, plays, and nationally recognized verse. Against his mothers wishes, the passionate young man fell in love and secretly became engaged to his neighbor, Adle Foucher. Following the death of Sophie Hugo, and self-supporting thanks to a royal pension granted for his first book of odes, Hugo wed Adle in 1822.

In the 1820s and 30s, Hugo came into his own as a writer and figurehead of the new Romanticism, a movement that sought to liberate literature from its stultifying classical influences. His preface to the play Cromwell, in 1827, proclaimed a new aesthetics inspired by Shakespeare and Velazquez, based on the shock effects of juxtaposing the grotesque with the sublime (for example, the deformed hunchback inhabiting the magnificent cathedral of Notre Dame). The play Hernani incited violent public disturbances among scandalized audiences in 1830. The next year, the great success of Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre Dame) confirmed Hugos primacy among the Romantics.

By 1830 the Hugos had four children. Exhausted from her pregnancies and Hugos insatiable sexual demands, Adle began to sleep alone, and soon fell in love with Hugos best friend, the critic Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve. They began an affair. The Hugos stayed together as friends, and in 1833 Hugo met the actress Juliette Drouet, who would remain his primary mistress until her death fifty years later.

Personal tragedy pursued Hugo relentlessly. His jealous brother Eugne went permanently insane at Victors wedding to Adle. Three of Victors children died before him. His favorite, Lopoldine, together with her unborn child and her devoted husband, died at nineteen in a boating accident on the Seine. The one survivor, Adle (named after her mother), would be institutionalized for more than thirty years.

Hugos early royalist sympathies shifted toward liberalism during the late 1820s under the influences of the fiery liberal priest Flic ite de Lamennais; of his close friend Charles Nodier, an ardent opponent of capital punishment; and of his father, a general under Napoleon I. He first held political office in 1843, and as he became more engaged in Frances social troubles, he was elected to the Constitutional Assembly following the February Revolution of 1848. A lifetime advocate of freedom and justice, often at his own peril, Hugos work linked art to the political realm. After Napoleon IIIs coup detat in 1851, Hugos open opposition created hostilities that ended in his flight abroad from the new government.

Hugos exile took him first to Belgium, and then to the Channel Islands of Jersey and Guernsey. Declining at least two offers of amnestywhich would have meant curtailing his opposition to the EmpireHugo remained abroad for nineteen years, until Napoleons fall in 1870. Meanwhile, the seclusion of the islands enabled Hugo to write some of his most famous verse and his masterpiece, the novel Les Misrables. When he returned to Paris, the country hailed him as a hero. Hugo then weathered, within a brief period, the siege of Paris, the institutionalization of his daughter for insanity, and the death of his two sons. Despite this personal anguish, the aging author remained committed to political change. He became an internationally revered figure who helped to preserve and shape the Third Republic and democracy in France. Hugos death on May 22, 1885, generated intense national mourning; more than two million people joined his funeral procession in Paris from the Arc de Triomphe to the Pantheon, where he was buried.

The World of Victor Hugo and

Next page