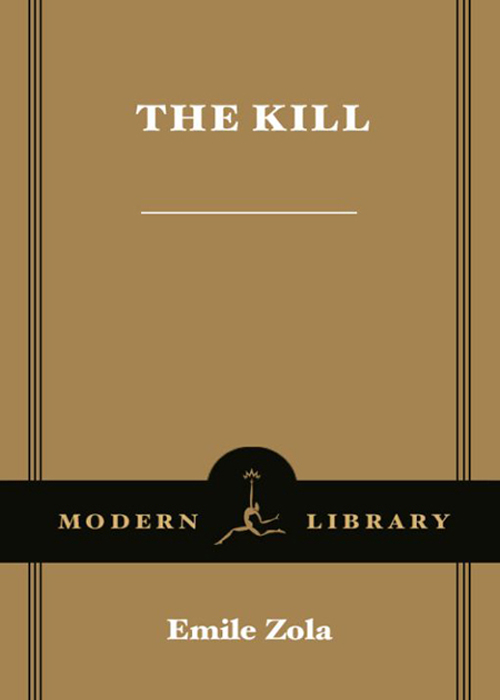

Emile Zola - The Kill (Modern Library)

Here you can read online Emile Zola - The Kill (Modern Library) full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2004, publisher: Modern Library, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Kill (Modern Library)

- Author:

- Publisher:Modern Library

- Genre:

- Year:2004

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Kill (Modern Library): summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Kill (Modern Library)" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Kill (Modern Library) — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Kill (Modern Library)" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

Arthur Goldhammer

Several years after Emile Zolas novel The Kill

The intermittence of modern life: the phrase is especially apposite of The Kill, whose style, in its best passages, is swift and transparent, like the glance of a contemporary, of your reader,and whose subject, more than the incestuous relationship between Rene Saccard and her stepson Maxime or the frenetic speculations of Aristide Saccardhusband of the one and father of the otheris in fact the capital of modern life, the city of Paris itself. For neither the speculation nor the incest would be conceivable without the modernity that is Paris, and that, far more than the brutal indecency of illicit sex, is the true object of Zolas meditation. And at the heart of that Parisian modernity is ambivalence, for the modern has no fixed identity. It is never anything but the antagonist in a perpetual quarrel of ancient and modern, a quarrel in which the ancient, the world we are perpetually losing, provides the only beacons in relation to which the identity of its ineluctably if ephemerally triumphant opponent can be located.

THE CAPITAL OF MODERN LIFE

In The Kill we gaze upon Paris as if attempting to get a fix on our precise location from a variety of angles: from the window of a restaurant high above the city on the Buttes Montmartre; from the childrens aerie atop the Htel Braud on the Ile Saint-Louis; from a carriage ambling through the scenic trumpery and social snobbery of the Bois de Boulogne or racing along new boulevards that paved the gas-lit way to perdition; from a mansion built in obedience to the dictates of the style Napolon III, that opulent hybrid of every style that ever existed;Naturalism was not so much an unvarnished description of what is as a willful imposition of images of a violence akin to natures own on the unnatural order of the new.

A violence akin to natures own: it was a problem for a novelist of Zolas epic ambition that the order of the new, being unnatural, lacked the palpable conflict inherent in the natural order in which the strong devour the weak. The transformation wreaked upon Paris in the years preceding the writing of The Killthe years of the Second Empire did not unfold like a play. It respected no unities of time or place; its action took place behind closed doors. Its battlefields were contracts and counting houses; its victories, expropriations, and quarter-point discounts on promissory notes. Though an epochal feat, which shaped history as surely as a decisive battle, it was not a feat of arms. It did, however, have a general: Baron Georges Eugne Haussmann, the visionary prefect [of the Seine], who saw himself as an artist of demolition, pragmatic, Protestant, modern, efficient.The function of this machine was to accelerate the flow of goods and consumers and thus to quicken the lifeblood of the French capital. Broad boulevards were its arteries. Zola evokes the rapturous response to the enhanced perfusion of the urban tissue:

The lovers were in love with the new Paris. They often dashed about the city by carriage, detouring down certain boulevards for which they felt a special affection. They took delight in the imposing houses with big carved doors and innumerable balconies emblazoned with names, signs, and company insignia in big gold letters. As their coup sped along, they fondly gazed out upon the gray strips of sidewalk, broad and interminable, with their benches, colorful columns, and skinny trees. The bright gap stretching all the way to the horizon, narrowing as it went and opening out onto a patch of empty blue sky; the uninterrupted double row of big stores with clerks smiling at their customers; the bustling streams of pedestriansall this filled them little by little with a sense of absolute and total satisfaction, a feeling of perfection as they viewed the life of the street.... They were constantly on the move.... Each boulevard became but another corridor of their house.

This absolute and total satisfaction is altogether kinetic. Zolas enumeration of visual stimulibalconies, signs, sidewalks, benches, storefrontsmoves as rapidly as the lovers coup, as if to signal slyly that the blur of motion is essential, that none of these delights can bear much scrutiny or be lived with for very long without turning into ennui, the affliction that drives Rene to sin.The curious insubstantiality of modern pleasure is driven home by the stark contrast with the ponderous and unusable satisfactions of a relatively static past, conveniently enclosed within the walls of Renes ancestral home, the Htel Braud:

Long suites of vast rooms with high ceilings dwarfed the old furniture, which was built low of dark wood. The dusky gloom was peopled solely by the figures in the tapestries, whose large, colorless bodies could barely be made out. All the luxury of the old Paris bourgeoisie was represented here, a luxury as unusable as it was unyielding: chairs whose oak seats were barely covered by a cushion of hemp, beds with stiff sheets, linen chests whose rough boards were singularly hard on frail modern finery.

Although Zola makes a half-hearted attempt at the end of his book to depict this sepulchral solitude as a moral order that would have yielded Rene, his latter-day Phdre, a happy life had she only bent herself to it, one feels through his pen the libidinal pull of the modern spectacle. He was the son, after all, of a civil engineer, a builder of bridges and canals, a proto-Haussmann possessed of heroic, visionary energy yet caught in the toils of stealthy financiers, who join with death to frustrate him of his prize.Hence the heroic myth of modernityEnlightenment made fleshis one that the son can wholeheartedly embrace. Light indeed becomes a physical and palpable presence in the novel of modern life. Everywhere in Zolas capital light is the ethereal creator of the new:

All the crystal on the table was as thin and light as muslin, devoid of engraving, and so transparent that it cast no shadow. The centerpiece and other large items looked like fountains of fire. Lightning flashed from the burnished flanks of the warming ovens. The forks, spoons, and knives with their handles of pearl could have been mistaken for flaming ingots. Rainbows illuminated the glassware. And amid this shower of sparks, this incandescent mass, the decanters of wine added a ruby tinge to table linen as radiant as white-hot metal.

Or, again:

It was not yet midnight. Down below, on the boulevard, Paris went rumbling on, prolonging the blaze of daylight before making up its mind to turn in for the night. Wavering lines of trees separated the whiteness of the sidewalks from the murky blackness of the roadway with its thunder of speeding carriages and flash of headlights. At intervals on either side of this dark strip newsdealers kiosks blazed forth like huge Venetian lanterns, tall and strangely gaudy, as if they had been set down in these precise places for some colossal illumination. At this time of night, however, their muffled glow was lost in the glare of nearby storefronts.

Similar passages could be multiplied at will. If this lightthis very physical light, this blazing gaslight, so different from the notional, metaphorical light of enlightened eighteenth-century thought was to dispel the funereal gloom of the old order, mountains had to be moved: again, mountains real and not metaphorical, mountains of fill and debris, and to mobilize the army of laborers needed to accomplish this, mounds of cash had to be accumulated.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Kill (Modern Library)»

Look at similar books to The Kill (Modern Library). We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Kill (Modern Library) and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.