A

CENTURY OF

EXCAVATION

IN THE

LAND OF THE

PHARAOHS

This work offers a unique overview of the work done in the field of Egyptology during the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries. An excellent starting point and reference for anyone fascinated by ancient Egypt, this book includes such topics as Mariette and his work, the beginnings of the modern period, the pyramids and their explorers, the temples, buried royalties, Tutankhamen, ancient life, and arts and crafts.

A

CENTURY OF

EXCAVATION

IN THE

LAND OF THE

PHARAOHS

JAMES BAIKIE

First published in 1924 by The Religious Tract Society.

This edition first published in 2009 by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxfordshire OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

First issued in paperback 2014

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

The Religious Tract Society 1924

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 13: 978-0-7103-0985-3 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-64644-4 (pbk)

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent. The publisher has made every effort to contact original copyright holders and would welcome correspondence from those they have been unable to trace.

PREFACE

I T is somewhat remarkable that, in spite of the considerable, if spasmodic, interest which is taken in the results of research in Egypt, no adequate account of the work of excavation has ever been written. The student who wishes to learn how, when, and where the facts and objects which interest him were discovered, has himself to excavate the desired information from the innumerable volumes of reports issued by the various exploration societies. It is much to be desired that someone who is master of the subject, and preferably, someone who has had actual experience of the work of excavation, should tell the story, not in a manner suited only to the ears of experts, but so that the educated public on whom in the long run excavation must depend for its resources, could appreciate and enjoy a narrative which ought to be as fascinating as any story of search for buried treasure.

This volume makes no pretension to the discharge of such a task. All that it attempts to do is to outline the story of certain aspects of the great work which has given us back so many of the wonders of the ancient civilisation of Egypt. Its omissions are, doubtless, many; but two will be at once conspicuous to anyone who has the slightest acquaintance with the subject. Nothing is said of the Search for the Cities, which in the closing years of the nineteenth century created so much interest, and resulted in so many identifications of sites; and nothing is said of the great work of Papyrus-hunting which has added so much to our knowledge of ancient life. These two matters were left untouched for reasons which seemed valid. In the case of the Cities, many of the identifications of the nineties are at present being questioned, and it seemed better to leave the matter till something like agreement is reached. In the case of the Papyri, the subject has become so specialised, and has developed so large a literature of its own as to render impossible any attempt to deal with it, on the scale which it deserves, in such a volume as the present.

It may be that at some time in the not far distant future, when controversy has resulted in more or less general agreement as to the sites, these two aspects of Egyptian excavation may be dealt with in a volume which may be a sequel and companion to this. My indebtedness to many authorities is manifest on almost every page of the book; but I wish specially to acknowledge my debt to Professor Sir W. M. Flinders Petrie, D.C.L., F.R.S., not only for the kindness which has allowed me to use the material of several of the plates in the book (7, 9, 10), but also for the constant inspiration and stimulus which his work has given to me, as to so many other students of the wonderful civilisation of Ancient Egypt.

JAMES BAIKIE.

CONTENTS

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

PLATE

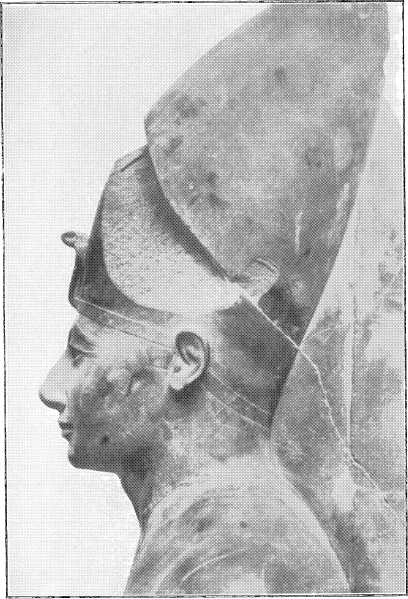

1. Portrait Statue of Thothmes III, Cairo Museum

A CENTURY OF EXCAVATION IN THE LAND OF THE PHARAOHS

T HE story of the beginnings of research into the wonders of antiquity in Egypt is unique in at least one point. In no other land does a conquering army march at the head of the pioneers of exploration; but the true beginnings of the century and a quarter of research which has given to us so many wonders from the Land of the Nile are to be found with that amazing troop of learned camp-followers who accompanied Napoleons army on the expedition of 1798. The wonders of ancient Egypt had never altogether been blotted from the memory and the interest of man, as was the case with some of the other lands of the Classic East. The pages of Herodotus, never fuller or more vivid than when he is dealing with Egypt, prevented that oblivion; and therefore Herodotus has some right to be named at the very beginning of the story of the exploration of ancient Egypt as the pioneer of pioneers. But the world was first really awakened to the richness of the Treasury of Egypt by the colossal production, twelve volumes of plates and twenty-four of text, which was the result of the untiring labours of Vivant Denon and his collaboratorsthe famous Description de lEgyptea work almost comparable in scale and grandeur with the monuments which it described. Few armies have left behind them such a memorial of their passage across a landthe more credit to the man whose inexhaustibly fertile brain conceived the idea of making even war subserve the interests of science.

Unfortunately, however, the tie with international strifes and jealousies, which had drawn the French savants originally to the Nile Valley, remained unbroken for many years; and questions of archology were continually complicated by questions of national pride and prestige, so that the early story of Egyptian exploration is not the story of pure research, conducted for the love of truth and of antiquity, but very often merely the story of how the representative of France strove with the representative of Britain or Italy for the possession of some ancient monument whose capture might bring glory to his nation, or profit to his own purse. There are few more melancholy chapters in the story of human frailty than those in which the early explorers of Egypt (if you can dignify them by such a name) describe how they wrangled and intrigued, lied and cheated, over relics whose mutilated antiquity might have taught them enough of the vanity of human wishes to make them ashamed of their pettiness.