1984 The University of North Carolina Press

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Hoisington, William A., Jr., 1941

The Casablanca connection.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. MoroccoHistory20th century. 1. Title.

DT324.H54 1984 964.04 83-5902

ISBN 978-0-8078-1574-8 (cloth: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4696-5462-1 (pbk.: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4696-5463-8 (ebook)

Preface

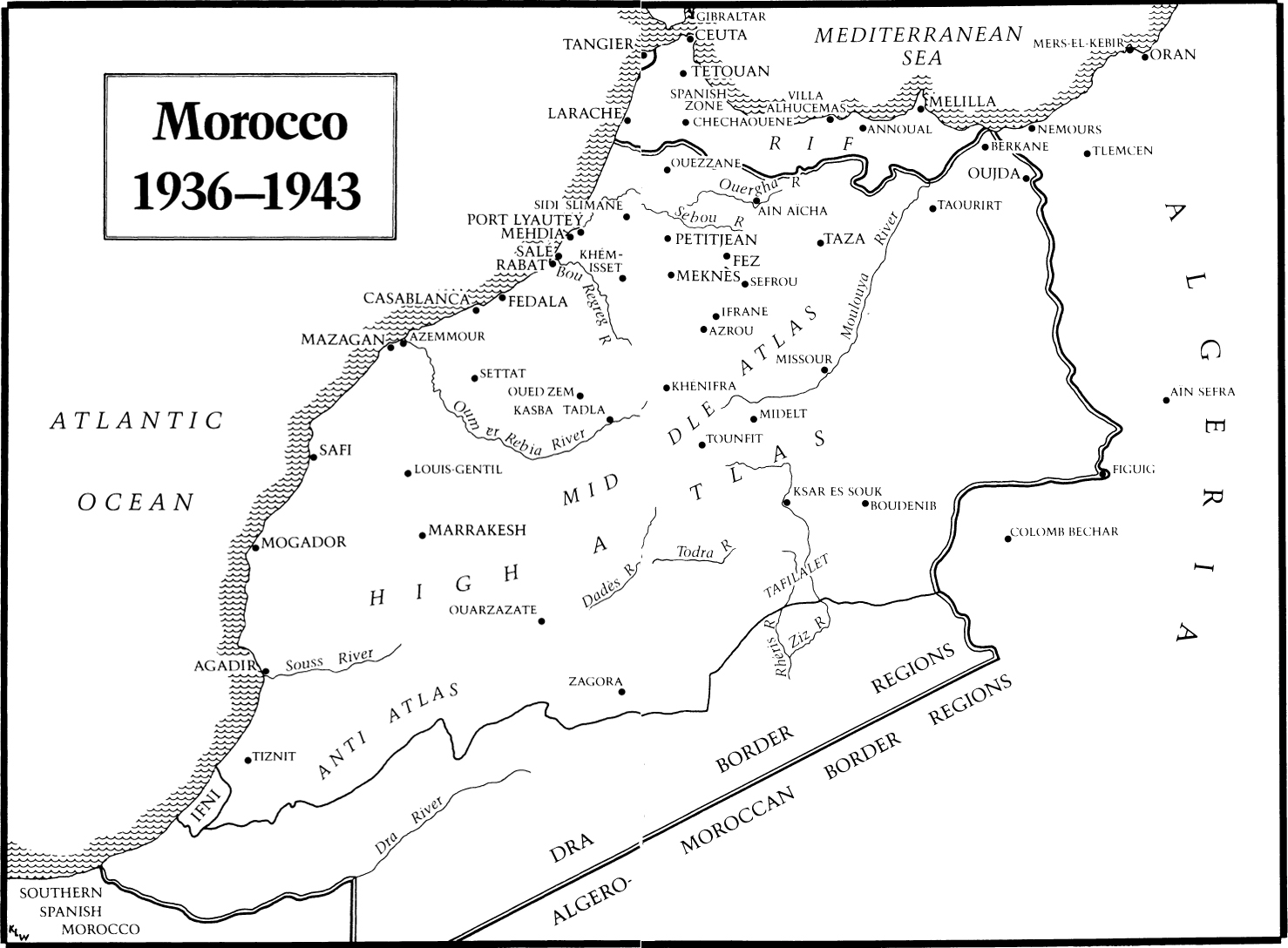

The subject of this book is General Charles Nogus and French colonial policy in Morocco from the Popular Front to the end of the Vichy regime in North Africa. Nogus was Frances sixth resident general at Rabat, the prize pupil of Marshal Hubert Lyautey (18541934), the creator of the modern Moroccan state whose maxims on colonial rule filled the notebooks of overseas administrators and foreign admirers and who is still revered by Frenchmen as a symbol of what was finest in their empire-building experience.1 Nogus had ideas of his own, but his real ambition was to emulate Lyautey, to work the marshals magic and breathe new life into the French protectorate over the sharifian empire at a moment of economic hardship, political disorder, and social crisis. Intelligent, disciplined, and sensitive, he was committed to creating bonds of interest and affection between Frenchmen and Moroccans that he hoped would be of ultimate benefit to France. I believe with all my heart, all my soul, and all my experience, Lyautey said, that the best way of serving France in this country, of ensuring the solidity of its presence, is to win over the soul and heart of this people.2 This was the task that Nogus wanted to pursue.

Nogus was also charged with protecting Morocco from the dislocations of the worldwide economic depression and shielding it from the disruptions of the Spanish civil war and World War II. Both jeopardized French control and made the contract with the sultan hard to fulfill. According to the 1912 Treaty of Fez, France had entered Morocco to establish a stable government based on internal order and security, to allow the introduction of reforms, and to ensure the economic development of the country. The new regime permitted France to occupy the land and to rule in the sultans name through the French resident general (commissaire rsident gnral), the holder (dpositaire) of all the powers of the Republic in Morocco. In return France pledged to safeguard the religious position [and] the traditional respect and prestige of the sultan; to support him against all dangers which may threaten his person or throne or which may compromise the tranquillity of his states; to sustain his central government, the Makhzen; and to protect the exercise of the Muslim religion throughout his empire.3 To Nogus fell the responsibility for keeping these promises.

During his tenure in Morocco, Nogus felt the reverberations of the erosion of French power and influence in Europe and the world. When the collapse came in 1940, North Africa was the one spot on the map where resistance to Germany might have continued. Instead, Nogus led the African empire into the Vichy fold. Geography, politics, and the colonial facts of life determined his course, which two years later led to an unhappy military collision with the Allies. The successor to Lyautey ended his career in exile and disgrace.

I am glad to acknowledge the grants from the American Council of Learned Societies, the American Philosophical Society, and the University of Illinois at Chicago. The French Colonial Historical Society fellowship at the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace made possible the writing of Cities in Revolt: The Berber Dahir (1930) and Frances Urban Strategy in Morocco, Journal of Contemporary History 13, no. 3 (July 1978): 43348, which has been incorporated into .

I owe an unrepayable debt to Colonel Guy and Odile de Verthamon, who permitted me unrestricted access to the papers of General Nogus. Agnes F. Peterson of the Hoover Institution also deserves special mention. I wish to record as well my appreciation to the family of Paul and Jeanette Binachon, who welcomed me to France twenty years ago, and to Gordon Wright, who introduced me to Frances history. Finally, I am grateful to Sharon, Anne, Sarah, and Kate, who shared every step of this project with me.

NOTES

. For a summary of Lyauteys career and a good bibliography, see Scham, Lyautey in Morocco. Also see Le Rvrend, Lyautey crivain. Opinion has always been divided on Lyauteys methods and accomplishments. For a recent irreverent evaluation, see Porch, The Conquest of Morocco.

. Lyautey, Aux personnalits venues pour linauguration du grand port de Casablanca et du premier tronon de chemin de fer voie normale de Rabat Fs, 4 April 1923, in Lyautey, Paroles daction, p. 395. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations of quotations from manuscript or published sources in French are mine.

. The Treaty of Fez (30 March 1912) is printed in Halstead, Rebirth of a Nation, pp. 27374.

The Casablanca Connection

ONE

The Lyautey Touch

In November 1938, when France was enjoying what Lon Blum called a cowardly sigh of relief that a European war had been averted over the Czechoslovakian crisis, an article appeared in La Revue hebdomadaire honoring Marshal Lyautey and his role in the creation of Frances overseas empire. The purpose was not only to celebrate Lyautey at a time when French heroes were scarce but to underscore the importance of Morocco to metropolitan France and to familiarize Frenchmen with the accomplishments of its current resident general, General Charles Nogus, Lyauteys spiritual heir, who had been posted to Rabat in 1936. Written anonymously by Noguss press secretary, it mixed public relations puff with an official view of what was happening in the western corner of North Africa. Lest Frenchmen forget the empire while their eyes were riveted on the Rhine, the author warned: The time is past when [Lyautey] could say that Moroccos fate depended upon what happened in Lorraine; today the fate of Lorraine, as well as that of our entire country, depends upon Morocco and the whole of our colonial domain. An imperial policy boldly undertaken and energetically supported by every group in the population is more than ever necessary to ensure the safety and independence of our country.

The empire coming to the aid of the homeland was a familiar tune. The French had heard it played during World War I. What was surprising, however, was that Morocco, which had been the scene of much social and political disturbance since 1934, was presented as an element of French strength rather than weakness. For this turn-about, Nogus was given full credit, especially in the important realm of native policy. The author insisted that Nogus, one of Lyauteys collaborators from the beginning, had faithfully taken up where the marshal had left off, reviving his precepts and his manner. With firmness and generosity, he had staved off the colonial collapse that the urban riots of 1936 and 1937 seemed to forecast and reestablished the protectorate on secure economic and political foundations. This was only part promotion. Fourteen years earlier, Lyautey had snugly wrapped the young colonel in his mantle. You know the country, you are imbued with my method/you are extra-intelligent and quick, and you radiate enthusiasm. On claiming the Residency, Nogus pulled the cloak tighter; he confessed that he had no other ambition than to walk in the footsteps of the illustrious marshal, his chief and venerated mentor.