David Blomfield thanks innumerable members of his own family, the staff of the National Army Museum, the Royal Engineers Library, and the British Librarys India Office Library and Department of Manuscripts, for the very considerable help he received during his research for this book.

First published in Great Britain in 1992 by

LEO COOPER

190 Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8JL

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd.,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Text copyright David Blomfield, 1992

Illustrations copyright Julian Mann, 1992

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

ISBN 0 85052 203 X

Typeset by Yorkshire Web, Barnsley, South Yorkshire

in Garamond Book 10 point

Printed in Great Britain by

Redwood Press

Melksham, Wiltshire

by Christopher Hibbert

(Author of The Great Mutiny India 1857)

This is splendid, no nonsense about it. We are fighting close up now, hurrying on the most rapid of sieges, working recklessly under fire.

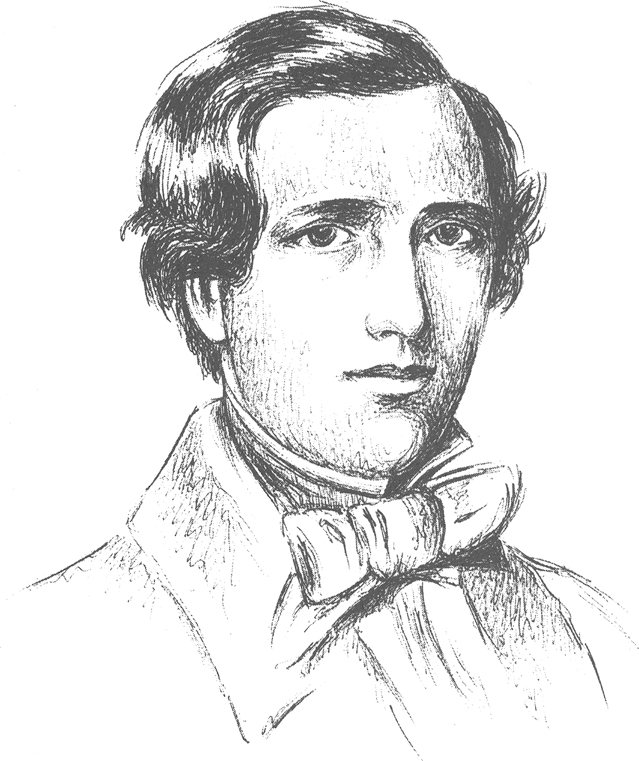

These words were written on the ridge outside Delhi on 12 September, 1857, and rarely has a young officers intense excitement in the danger of war been so well conveyed.

On the evening of the next day their author, Lieutenant Arthur Moffatt Lang of the Bengal Engineers, was ordered to inspect the breach which the British Armys heavy guns had made in the walls surrounding the city. Behind these walls thousands of mutinous Indian troops were defying their British masters in the name of Bahadur Shah II, descendant of the Moghul Emperors who had ruled here before the British came. On the outcome of the proposed assault depended the immediate future of Britains Empire in India.

Lieutenant Lang was told to climb up the steep slope towards the breach as soon as it was dark and to report as to whether or not an immediate assault was practicable. I preferred going when I could see, his account continues, so went at once and taking four riflemen crossed the road leading to the river and slunk up through some trees to the foot of the glacis. Leaving my riflemen under a tree, I ran up the glacis and sat on the edge of the counterscarp and examined the appearance. I ran back, fired at, and coming in was fired at by our own sentries. In this characteristically modest way Lang described a brave reconnaissance which many thought should have won him a Victoria Cross. His concise report led to the British commanders deciding upon the assault on Delhi which was ordered to take place that night.

The letters and diaries in which Lang vividly describes this assault have long been known to historians of the Indian Mutiny. But they have not before been published in book form; and readers will be deeply grateful to Leo Cooper for bringing them out in this edition and to David Blomfield for his skilful editing.

Arthur Moffatt Langs account is memorable both as a revealing self-portrait of a young Victorian officer and as a chronicle of the savage conflict in which he played so courageous a part. His delight in the excitement of war is evident from the moment he leaves Lahore for Delhi, choking with indignation, as he puts it, at the cruelty with which the poor ladies had been treated at Meerut, where the Mutiny had broken out, and hoping no quarter, no mercy will be the cry when we have the upper hand.

It is extraordinary that Lang was not shot himself, that while taking part in some of the heaviest fighting of those years, he was not once hit until when the conflict was almost over he was sent spinning by a stinging crack on the shoulder from a bullet which glanced off his pouch-belt. At Agra he described riding through sepoys like a wild Crusader, slashing and thrusting. At Delhi, where he scrambles breathlessly across the tumbled masonry, the bullets seem to pass like a hissing sheet of lead over his head. But on we rushed, shouting and cheering, while the grape and musketry from every street and from rampart and housetop knocked down men and officers. It was exciting to madness.

As well as the sound of fury of fighting, Langs diary evokes the beauty of the Indian landscape, the broad rivers with their green banks, the splendid, gleaming mosques and the red walls of forts glowing in the evening sunlight, forest walks where peacocks strut proudly beneath the trees and monkeys scamper and chatter in the branches, and over all is the strong scent of the babul blossoms. There are well-observed and entertaining character sketches: not least that of the Commander-in-Chief, Sir Colin Campbell himself, a Glaswegian carpenters son with a ferocious temper and a sharp, pink, lively face, gesticulating with both hands and hissing through clenched teeth as he argues furiously with the Chief Engineer. There are glimpses, too, of English ladies in bonnets, cheering the troops as they march across the bridge into Agra; of picnics at the Taj Mahal and dances on its smooth marble floor. Contrasting with these is the pervading brutality, the horror of the scenes at Cawnpore where evidence of the massacre lies scattered upon every side bloodstained slippers and socks and bits of clothing, letters and leaves of books and locks of long hair. No officer standing in these rooms spoke to another. I know I could not have spoken. I felt as if my heart was stone and my brain fire, and that the spot was enough to drive one mad. I thought when I had killed twelve men outright at the battle of Agra, that I had done enough: I think now I shall never stop if I get a chance again.

For all his protestations of hatred for the mutineers and for all the harsh treatment to which his own native soldiers were occasionally submitted at his hands, Lang was capable of profoundly tender feelings. He writes in moving terms of the death of his friend Home, a horrid dream from which he longed to wake, and of that of Elliot Brownlow, such a splendid fellow, God bless him. Indeed, the death of Brownlow cast a gloom over the campaign as far as it concerns me, he writes, and has rendered it distasteful to me and spoiled all my pleasure in war and victory and Lucknow. The young man who had professed himself intensely happy while campaigning, who had thanked God that he had chosen to live the life of a soldier, now had had enough. He had been fighting as an infantry man, revelling in the excitement. He now wanted nothing more than to return to Lahore and to marry the girl with whom he had fallen in love before he left. So, declining more adventurous appointments, he went back to a comparatively humdrum life in Public Works.

His subsequent career was one of only moderate distinction. He was eventually promoted colonel and in 1908 awarded a C.B. It seemed a modest crowning honour for a soldier who had been recommended three times for the Victoria Cross and was four times mentioned in despatches. But he now at last has a fitting memorial: it is contained in the pages that follow.