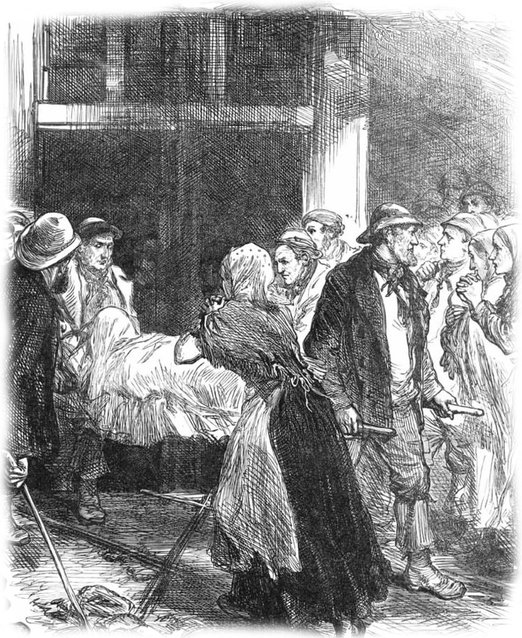

Bringing out the dead . ..

First Published in Great Britain in 2006 by

Wharncliffe Books

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Jack Nadin 2006

9781783408344

The right of Jack Nadin to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publishers.

Typeset in 10/12pt Palatino by Concept, Huddersfield.

Printed and bound in England by CPI UK

Pen and Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of

Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime,

Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe Books,

Pen & Sword Select, Pen and Sword Military Classics

and Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2BR

England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Table of Contents

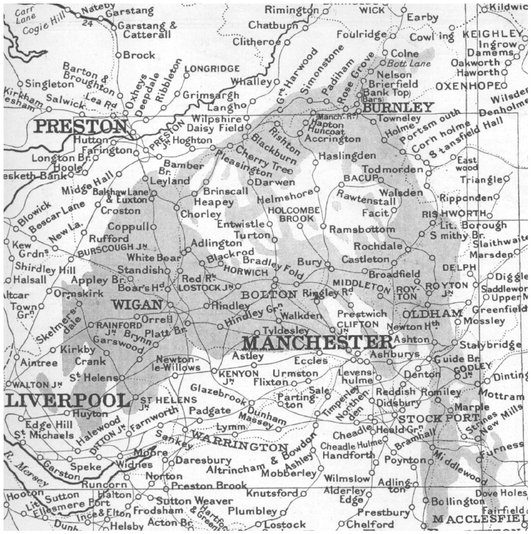

The Lancashire Coalfield and the area covered by this book . Authors collection

Foreword

There have been numerous studies concerning particular mining disasters but few regional and general accounts. Lancashire Mining Disasters is the first of what is hoped will be an authoritative series of publications.

Jack Nadin is a former miner with a great interest in mining history. Anyone reading his descriptions of the terrible events and circumstances surrounding the disasters will appreciate his empathy towards Lancashire miners.

Jack has included in his study details of thirty-six disasters, from the inrush of water at Ladyshore Colliery in 1835 to the explosion at No. 3 Bank Pit (Pretoria) on that dreadful December day in 1910. He also provides useful background information about each pit before and after each catastrophic event. Jacks research findings, including lists of fatalities, will be of interest to the increasing number of family historians with Lancashire mining ancestry.

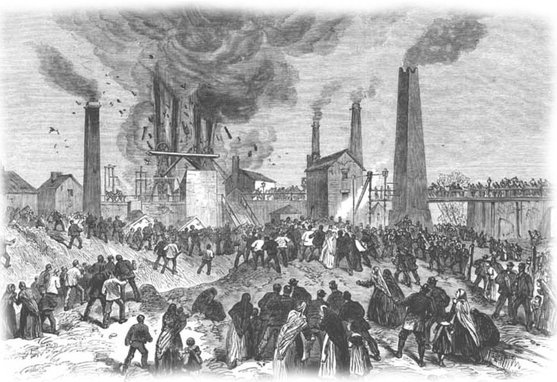

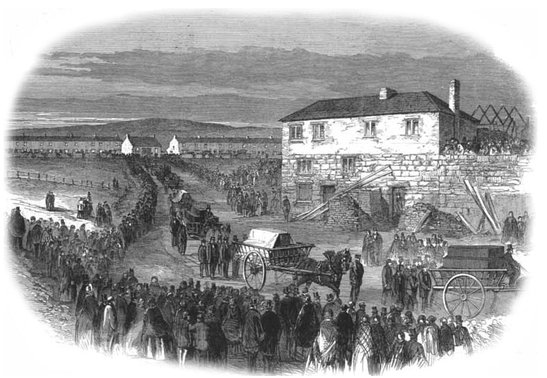

Major mine disasters were always national news. From mid-Victorian times the big explosions attracted the interest of the Illustrated London News (founded in 1842), the first mass circulation journal dedicated to topical events. The horror associated with men and boys burnt, maimed and gassed, together with dreadful scenes of mass mourning were ideal subjects for graphic representation. Accounts of extraordinary bravery and rescue also captured the public imagination. By 1853 the Illustrated London News had published twenty mine disaster engravings. The original drawings, executed from eyewitness accounts and on the spot interpretation, were completed by artists of Royal Academy status. Competition to the Illustrated London News was provided by The Graphic who had the foresight to employ socially aware young artists. National, regional and local newspapers published detailed accounts of disasters, along with reports of inquests and lists of fatalities, information otherwise confined to official sources.

Despite all the media attention far more injuries and deaths occurred in day-to-day accidents, especially at the coal face. By the time of Senghenydd in 1913 average annual death rates had fallen to 1.3 per 1,000 (from over 4 per 1,000 in the 1850s) but of course statistics were no consolation to bereaved families. However, what made the big disasters such singular and catastrophic events was that a significant proportion of the male population of a mining settlement or village could be wiped out overnight, leaving scores of widows and hundreds of orphans. Some families were particularly hard hit, having lost loved ones in previous accidents or with several members killed in a single disaster. Public subscriptions and relief funds may have helped but there was no real compensation available for households already not far off poverty level. Perhaps the only parallel was the great local loss incurred by the close-knit Pals regiments on the Somme.

Jack Nadins book is a welcome addition to our developing knowledge and appreciation of our social and industrial history and serves as a great tribute to Lancashire miners, their families and communities.

Brian Elliott

Introduction

Coal mining in Lancashire was a major employer from the early 1840s, when larger pits were being sunk to meet the ever-increasing demand of the Industrial Revolution. The hungry mills, factories, and foundries were crying out for coal which was to make England the greatest manufacturing nation in the world. It was coal that fuelled these industries and created the Great in Great Britain. The factories, the foundries and steelworks supplied the world, but coal supplied the means of making these goods for export and home use. It was also from the early 1840s, that the terrible colliery disasters occurred, and continued to do so well into the twentieth century. In the early days, labour was cheap and so was life, and many men and boys perished in mining accidents. Most of these were caused by underground explosions when proper mining science was in its infancy, and lessons were slow to be learnt. Disaster after disaster wiped out hundreds, even thousands of lives, before the authorities and mine owners began to act. It is also true that many of the accidents were caused by the men and boys employed as miners themselves. The Davy lamp, and others such makes, had safety features to prevent explosions and were readily available. But the miners hated the new safety lamp, which barely gave off enough light to see with, referring to it as a candle in a stocking. In the hands of the men, and in spite of locks and other devices to prevent opening, the tops of lamps were often taken off, even in gassy workings, or the gauze pricked to make a hole, exposing the flame, with terrible consequences. Sheets, known as brattice were erected underground to control and direct air currents but they were often taken down (once the underlooker was out of sight), being a hindrance to the working miner; consequently gasses accumulated and were ignited by the open lamps. Indeed, a number of mines continued to use naked flames, or candles, even in the gassiest of seams, both men and managers knowing full well the effects and danger involved in doing so.

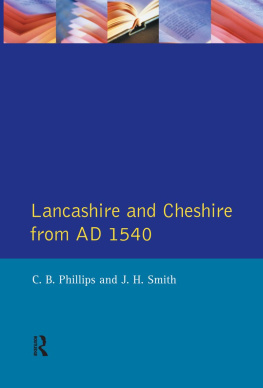

A typical mid-nineteenth century disaster scene, re-created by an artist from the Illustrated London News. www.cmhrc.co.uk