I would like to thank Karen and Merlin Unwin for allowing me to write the volume on The County Palatine in their County series. I must also acknowledge help in the provision of photographs by Getty Images, Jon Ward Allen, Ray Ball, Mike Harding and the wonderful Ken Dodd; also to R.F.G Hollett & Son, Wigan History Shop, Leigh Library, Bolton Library and Art Gallery, Manchester Central Reference Library and the Harris Library and Art Gallery. Our County is so fortunate in its wealth of libraries and art galleries (see page ). Visit them!

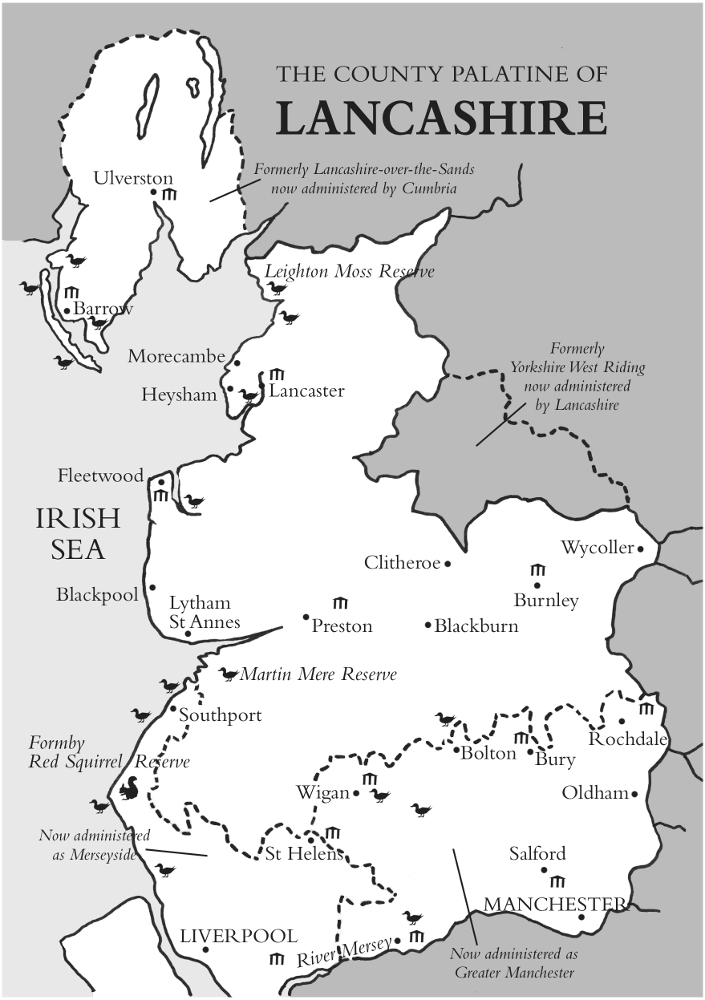

In 1974, Edward Heath decided to demolish over 800 years of our history. He savaged our traditional counties and replaced them with new artificial ones that few wanted. Lancashire was particularly badly hit. The southwest was hived off with Wirral to make Merseyside. The southeast was tacked onto a bit of Cheshire to form Greater Manchester. To the north, all Furness that was once Lancashire-over-the-Sands (the sands of Morecambe Bay) was taken, along with all Cumberland and Westmorland, to create Cumbria. Finally, a chunk of south Lancashire, including the towns of Widnes and Warrington, was ceded to Cheshire.

I live in the village of Lowton St Luke which is (just) in Heaths Greater Manchester. My postal address is Lowton, Warrington, Cheshire, and the postal sorting office is in Newton-le-Willows, Merseyside! Yet I am a Lancastrian, and proud of it.

A Yorkshire tyke writing a similar book about their county would similarly protest. Indeed, they did protest and had Heaths ridiculous Cleveland obliterated. Before 1974 the River Hodder was part of the border between Lancashire and Yorkshire, and then the Fairsnape ridge, putting most of the Forest of Bowland in the County of the White Rose. Further south, the old boundary put villages like Sawley and Gisburn, Barnoldswick and Earby firmly in Yorkshire. No longer, officially. Heath plonked them into Lancashire along with some fells in the Lune valley.

The effect on our county has been great and often laughable. Up to 1974 the Lancashire coastline was 216 miles long; the new Lancashire has a coastline of only 118 miles. Today the most southerly point in official Lancashire is near the villages of Sefton and Kirkby, where most people speak with a scouse accent, whereas the most northerly point of Merseyside is the north end of Southport, which is by the Ribble, not Mersey! Up to 1974, Coniston Water was Lancashires largest lake; today it is Stocks Reservoir that, up to 1974, was in Yorkshire! Until 1974, Lancashires highest point was the Old Man of Coniston (at 3,631'); today it is Leck Fell (at 2,057'). And if you are into cricket, most clubs in the Lancashire League are not now in Lancashire, nor is Old Trafford, HQ of Lancashire Cricket Club.

Greater Manchester! Ugh!

Away with it all, I say. This book deals with The County Palatine of Lancaster, and its boundaries are the pre-1974 ones (forgive me if I stray into what was Yorkshire, but if I do there will be a good reason). There are other Counties Palatine, but Lancashire is the only The County Palatine. The County Palatine has, at its head, the Duke of Lancaster, and the dukedom is held by the Crown. So when drinking the Loyal Toast, whilst non-Lancastrians say, The Queen, we raise our glasses to The Duke of Lancaster!

An awful lot has happened in Lancashire and to include it all would require several big tomes. I have therefore had to be highly selective. I hope that you enjoy what I have selected, and that it makes you proud to be a Lancastrian (or extremely jealous if you are not).

Malcolm Greenhalgh

Lowton, Lancashire

Lancashire vied with Cornwall for the title, Poorest County in England, up to the 18th century. Let me give an instance from 1515, in terms of wealth per 1000 acres of land. That year the average for all English counties was 66/1000 acres, our near neighbour the West Riding of Yorkshire was pretty poor at 11.30/1000 acres, but Lancashire a pathetic 3.80/1000 acres.

The reason for this dreadful state of affairs was the nature of the countryside. Nine estuaries (Mersey, Alt, Ribble, Wyre, Lune, Keer, Kent, Leven and Duddon) dominate the coastline, the Wyre, Lune, Keer, Kent and Leven entering Morecambe Bay. They greatly hindered movement in a north-south direction and were crossed at the travellers peril (see page ). Inland, the coastal plain that dominates the hinterland south of the Lune and continues in a broad swathe on either side of the Mersey as far as Manchester, was largely treacherous peat bog that we call moss or mossland after the sphagnum moss that dominates these raised bogs. Beyond the mosslands, the land quickly rises in inhospitable steep-sided moorland. So there were only scattered patches of ground with good, well-drained soil where farmsteads and villages could be built. Nothing illustrates this topographical problem better than transport systems passing north-south through the county, especially between Preston and Lancaster. On a band of well-drained land, often only a quarter of a mile wide, a road was built by the Romans around 80AD, and parallel with this Roman road are now the A6 trunk road, the M6 motorway, the West Coast railway lines, and part of the Lancaster Canal. To the west are mosslands, and to the east steep fellsides.

So what happened in Lancashire in the 200 years between 1750 and 1950, to turn what was an impoverished county into one of the wealthiest?

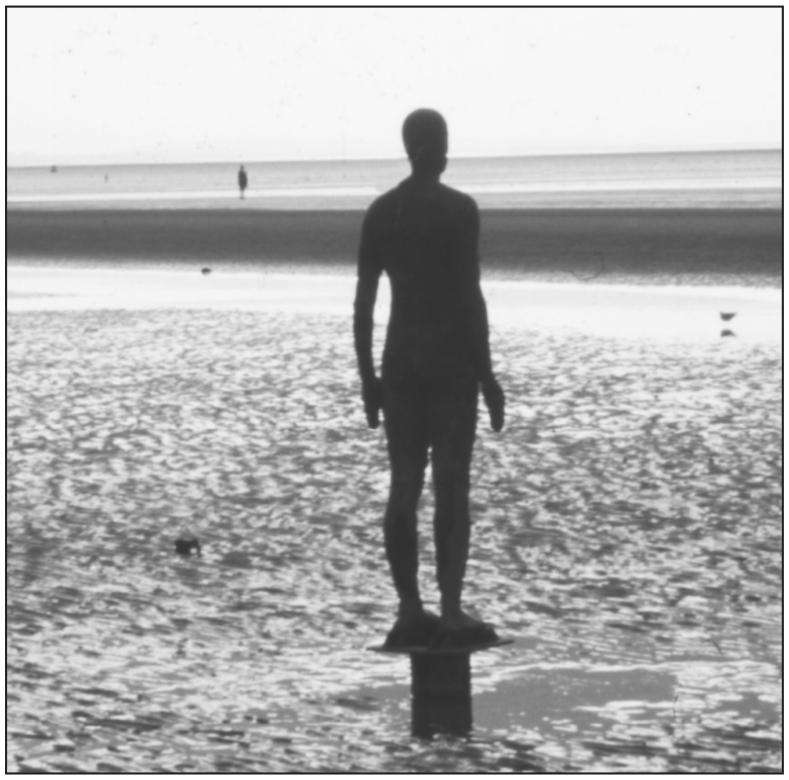

Anthony Gormleys sculpture Another Place on the Mersey estuary at Crosby. It consists of 100 cast iron figures: naked males, scattered over an area 2 miles by half a mile. They all stand to attention and look seawards as the tide ebbs and flows, the bodies rising and sinking beneath the tide in eerie fashion

First of all, after several failed attempts, techniques were developed to reclaim the mosslands. This involved digging deep channels and pumping the water away to the nearest river. Rank vegetation was then burned, marl or lime scattered over the land to reduce the acidity of the peat, and then the drying moss was ploughed. Fertiliser was then incorporated. Often this was night soil human excrement brought from the dung heaps of the growing towns. Today we can still see signs of this process, in the form of tiny shards of broken pottery scattered on the surface of newly-ploughed fields. When the town dweller broke a cup or plate, it was thrown onto the dung heap and became part of the night soil.

Mosslands provide very fertile soil for growing vegetables and cereals: so productive that the cost of reclamation was more than covered by the income from the first years crop. And these mosslands provided much of the food needed by the growing townships.

The second factor was the huge increase in the exploitation of locally available raw materials and the perfect position of ). That is why Liverpool was, at one time, the wealthiest city in England, if not the world, and has more beautiful listed buildings than any other outside London.

Lancashire had plenty of its own raw materials. South Lancashire sits on coal, lots of coal. It is reckoned that there is more coal left underground than was ever brought to the surface (page ). So the iron and steel was on hand to manufacture mill looms, railway lines, railway and other essential engines, and so on.

Lancashire is also wet. Did not John Arlott once remind his listeners, when rain interrupted play at Old Trafford, that Manchester is the only city in the world where they have lifeboat drill on the buses! As the towns grew, so this rain was increasingly collected in reservoirs built in the nearby moorlands. The moors have a peat covering over a rock called millstone grit, and these render the water collected to be slightly acidic and very soft, which was ideal for use in the steam engines that drove the Industrial Revolution, and in the production and dyeing of cotton fabrics. It also makes the perfect cup of tea.