PETERLOO

The Story of the Manchester Massacre

Jacqueline Riding

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

MANCHESTER, 16 AUGUST 1918

On a hot late summers day, a crowd of 60,000 gathered in St Peters Field. They came from all over Lancashire ordinary working-class men, women and children walking to the sound of hymns and folk songs, wearing their best clothes and holding silk banners aloft. Their mood was happy, their purpose wholly serious: to demand fundamental reform of a corrupt electoral system.

By the end of the day fifteen people, including two women and a child, were dead or dying and 650 injured, hacked down by drunken yeomanry after local magistrates panicked at the size of the crowd. Four years after defeating the tyrant Bonaparte at Waterloo, the British state had turned its forces against its own people as they peaceably exercised their time-honoured liberties. As well as describing the events of 16 August in shattering detail, Jacqueline Riding evokes the febrile state of England in the late 1810s, paints a memorable portrait of the reform movement and its charismatic leaders, and assesses the political legacy of the massacre to the present day.

As fast-paced and powerful as it is rigorously researched, Peterloo: The Story of the Manchester Massacre adds significantly to our understanding of a tragic staging-post on Britains journey to full democracy.

Contents

For Lancashire Witches,

past, present and future

At Waterloo there was man to man, but at Manchester it was downright murder.

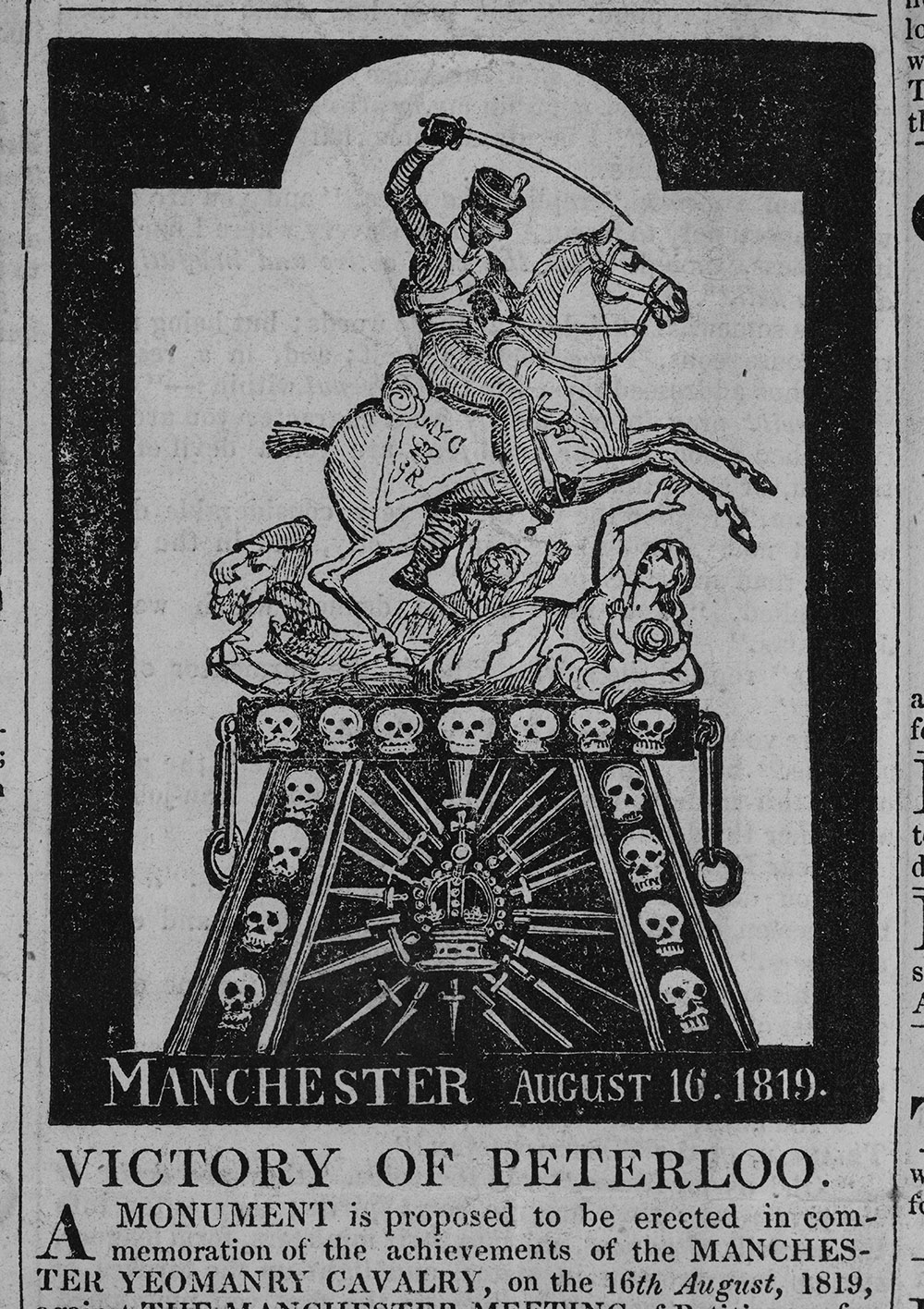

Victory at Peterloo by George Cruikshank, from William Hones A Slap at Slop and the Bridge-Street Gang , 1822.

(The John Rylands Library, Manchester)

by Mike Leigh

As we worked on the film Peterloo , all of us, on both sides of the camera, were continually struck by the ever-increasing contemporary relevance of the story. Despite the spread of universal suffrage across large parts of the globe poverty, inequality, suppression of press freedom, indiscriminate surveillance and attacks on legitimate protest by brutal regimes are all on the rise.

Peterloo is of seminal importance, yet many people have never heard of it, including, curiously, generations of native Mancunians and Lancastrians. I myself grew up in Salford. As a boy, I trod the streets that stand where St Peters Field once was. The Midland Hotel occupies the site of Buxtons house, from where the misguided magistrates watched the massacre unfold. Next door is the Central Library, where I received my early theatrical education at the tiny Library Theatre, the local professional repertory company. As a teenager, I attended meetings of the Manchester Branch of the Gilbert and Sullivan Society, which took place at the (Quaker) Friends Meeting House, dating from 1795, which played such a critical role at Peterloo.

And then there was the Free Trade Hall, now the Radisson Hotel, which these days boasts a newish red plaque commemorating Peterloo. It was here that I attended Hall Orchestra, jazz and folk concerts, heard Bertrand Russell address CND rallies and delighted to see Tom Lehrer perform, and where I directed Big Basil , an early play of mine, for the Manchester Youth Theatre in 1968.

Early in our research, when Jacqueline Riding and I walked the Peterloo site with expert Robert Poole, I was shocked to realise how ignorant I had once been about the bloody events that had taken place on that very spot less than a century before my parents were born.

My primary school was next to Cromwell Bridge, which crosses the River Irwell. There, we were repeatedly told about the Siege of Manchester in 1642, during the Civil War but Peterloo was never mentioned. Why, during our educational visits to cotton mills and soapworks and bread factories, were we never marched around the Peter Street area, and made to picture and re-live what was the most important event apart from the Blitz ever to take place in these streets? And why, in O Level History, was Peterloo dismissed as a mere footnote?

A lifetime later, as we approach its bicentenary, the whole world can now learn the truth about Peterloo. This splendid book will bring a new freshness and clarity to the story; and so too, I hope, will Peterloo the movie, albeit in a different way. Jacquelines book is a comprehensive, detailed and accurate history, whereas my film is a dramatic distillation not a documentary, but nonetheless, I hope, true to the spirit of Peterloo.

The film and the book complement each other. Please enjoy them, but do be sure to be both moved and horrified by them, too.

Two Fields

The scene of misery

On Sunday 18 June 1815, two armies, numbering 140,000 men and boys, faced each other across open fields and low-rising arable land, fourteen miles south of Brussels in the Kingdom of the Netherlands (now Belgium). They would decide, once and for all, Europes fate after twenty-two years of catastrophic war. The rain had been pouring down for several days, making a swamp of the terrain that the Commander-in-Chief of the combined British, Dutch and Hanoverian (or Allied) army, Field Marshal His Grace the Duke of Wellington, had selected as the field of battle.

Among those waiting in tense anticipation for his commanding officers signal was John Lees, a cotton factory owners son from Oldham in the northern English county of Lancashire. What possessed him to take such a step is not known. 1812 was the year when Great Britain commenced war with the United States of America and when Napoleon Bonapartes hubristic decision to march on Moscow turned into a decimating retreat through a bitter Russian winter. In faraway Lancashire, the weavers were experiencing mass unemployment and terrible deprivation. There were some in Britain, landowners and farmers for example, who profited from the war, but many more who had been and continued to be brought to their knees by it. Taxation was one burden from which no one was immune, regardless of how small or irregular their wages, whether direct (via property or earnings) or indirect (via goods). Income tax had been devised in 1798 by William Pitt the Younger to finance the ongoing war effort. At the resumption of the war after the short peace between 1802 and 1803, the then prime minister, Henry Addington (in office until 1806, afterwards elevated to the peerage as Lord Sidmouth), revised the system, doubling those liable to pay it while significantly reducing evasion through collection at source. For the majority of Britons, who had no vote in national parliamentary elections, this was taxation without representation. And as national government did little beyond fighting wars no poor relief, policing, medical care, schooling for most citizens the return on decades of taxation, beyond more war and deeper national debt, was negligible.

1812 was also infamous for the assassination of Prime Minister Spencer Perceval shot in the lobby of the House of Commons by a disgruntled merchant, John Bellingham and for the violent Luddite Revolt, when handloom weavers vented their frustration and despair, exaggerated by wartime hardships, on the water and steam-powered machines that were transforming textile production, uprooting thousands of the working and labouring class from individual cottage industries to the vast weaving and spinning sheds of the cotton mills that have come to symbolize the Industrial Revolution of Englands Midlands and North. Both events appeared to signal that a general rising against the government was about to break out, or even revolution against the state itself, as in the American colonies in 1776 and then, more terrifyingly, France in 1789. Fears that enduring revolutionary zeal was spreading to the United Kingdom, fuelled by the writings of the English republican radical Thomas Paine ( Common Sense , 1776, and The Rights of Man , 1791), left the longstanding Tory government, in power since 1783, on constant alert. Paines message of liberty, equality and the potential of a government based on a true representation of the people, rather than the Old European systems founded on hereditary privilege and monarchical rule as Paine himself put it, to begin the world over again