CONTENTS

ABOUT THE BOOK

Unity of the oppressed can make a difference in politically uncertain times

A peaceful protest turned tragedy; this is the true story of the working class fight for the vote.

On August 16 1819, in St Peters Field, Manchester, a large non-violent gathering demanding parliamentary reform turned into a massacre, leaving many dead and hundreds more injured.

This catastrophic event was one of the key moments of the age, a political awakening of the working class, and eventually led to ordinary people gaining suffrage. In this definitive account Joyce Marlow tells the stories of the real people involved and brings to life the atrocity the government attempted to cover up.

The Peterloo Massacre is soon to be the subject of a major film directed by Mike Leigh.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Joyce Marlow was born and raised in Manchester in the 1930s. Soon after the Second World War she became an actress and later a full-time writer. A life-long Labour supporter and feminist, she edited anthologies such as The Virago Book of Women and the Great War, as well as Suffragettes: The Right to Vote for Women. She was also the winner of the Romantic Novelists Best Historical Novel Award. Married with two sons, she lived in the High Peak District in Derbyshire.

.

To the memory of my mother Mary Thorpe Lees

PETER LOO MASSACRE !!!

Just published No. 1 price twopence of PETER LOO MASSACRE Containing a full, true and faithful account of the inhuman murders, woundings and other monstrous Cruelties exercised by a set of INFERNALS (miscalled Soldiers) upon unarmed and distressed People.

Manchester Observer, August 28th, 1819.

As the Peterloo Massacre cannot be otherwise than grossly libellous you will probably deem it right to proceed by arresting the publishers.

Letter from Home Office to Magistrate Norris, August 25th, 1819.

AGRICULTURE COULD NOT HAVE MADE SUCH A PLACE AS MANCHESTER

Among the thousands of British troops who fought at Waterloo was an eighteen-year-old named John Lees. He came from Oldham in Lancashire. Had he died at Waterloo we should never have heard of him, for the blood of such ordinary young men stained the Belgian cornfields red. But he survived the three days of bitter fighting that culminated on June 18th, 1815, in the final defeat of Napoleon and the end of twenty-odd years of war. He was discharged and returned home to follow his trade as a cotton spinner. Four years later he was dead as the result of injuries received on another field.

The ground on which John Lees sustained his mortal wounds was an area of open land near the centre of Manchester known as Saint Peters Field. The date was August 16th, 1819, and the occasion was a mass meeting in support of Parliamentary reform. The injuries were inflicted by fellow Lancastrians, who were members of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry Cavalry, and by the 15th Hussars, ex-comrades in arms from Waterloo. Before he died John Lees said he was never in such danger at Waterloo as he was at the meeting, for at Waterloo it was man to man but at Manchester it was downright murder. He was not alone in this assessment. Other people seized upon the presence of Waterloo veterans such as himself in the unarmed crowds, and upon the actions of the 15th Hussars on the June and August days.

On the August day the savage sobriquet Peterloo was bestowed.

John Lees lingered in agony for three weeks after Peterloo. His inquest was used as a test case to try and prove that what happened on Saint Peters Field had been downright murder. Thus in death his name rang round England. But if in life he was unsung he was also, by being such an ordinary young man, typical of thousands of Lancastrians. The reasons that made him attend the meeting also drove half the 60,000 present, the army of John Leeses who do not move until a situation has reached desperation point or the way has been so clearly sign-posted they cannot fail to follow. Of these reasons a few were understood by him at the time, others he was not sufficiently clever or educated to grasp, while others need a retrospective eye.

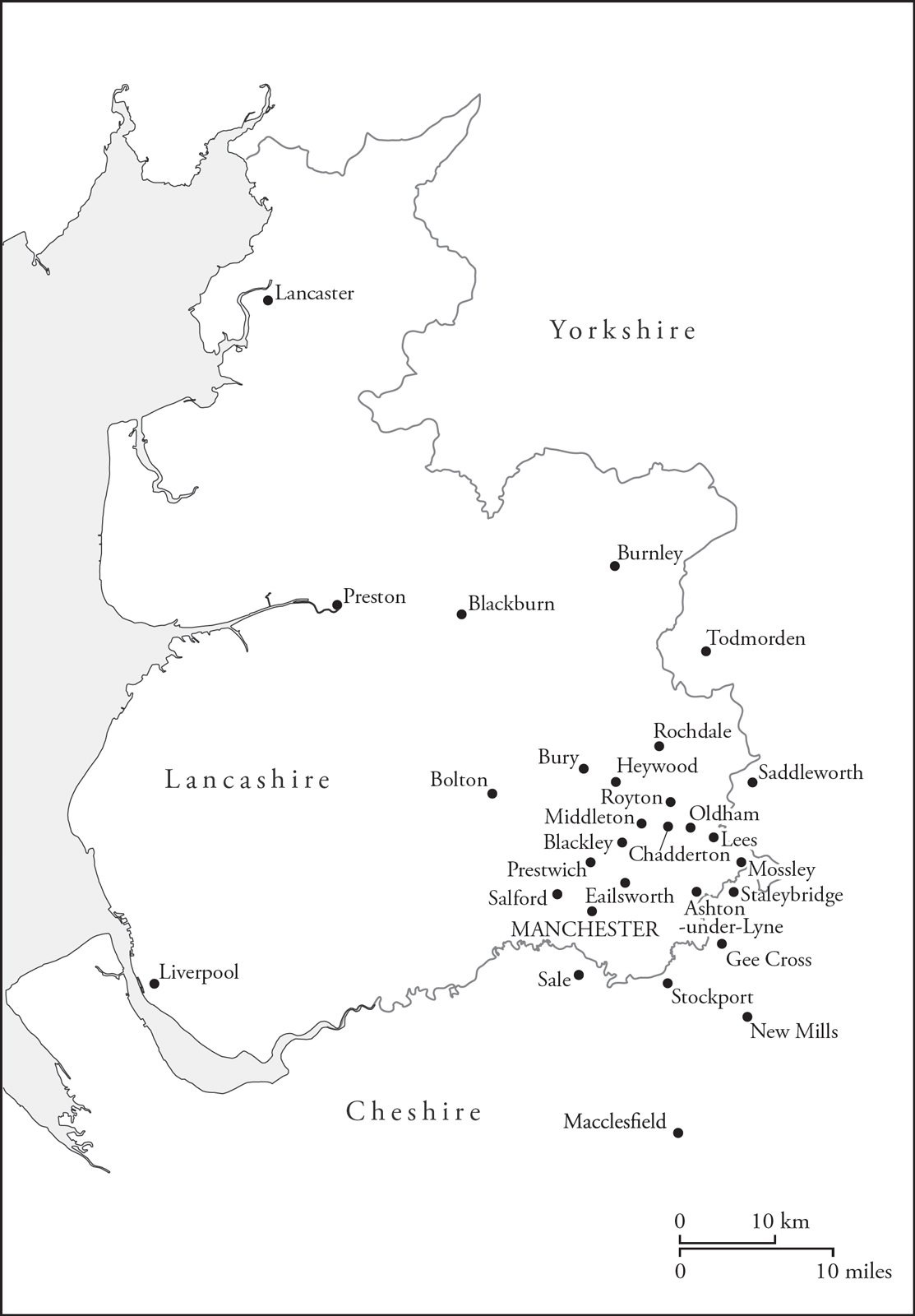

The stuff of which Peterloo was made has as many threads as a length of woven cotton, but the main ones were contained in John Leess brief life span. For he was a child not only of the Industrial Revolution but of the world cradle of that revolution (or evolution). A small-time cotton manufacture had existed in south-east Lancashire since the beginning of the seventeenth century, with Manchester as its weak heart and the villages such as Oldham, Middleton, Rochdale and Royton as the anaemic arteries. In the old days a cosy structure had existed which memory made cosier as it disappeared. The merchants bought the raw cotton from the Liverpool dealers, sold it to small-time masters who in turn sold it to spinners working in their cottages. When the yarn was spun it was sold back to the masters or directly to the aristocrats of the trade, the hand-loom weavers, who duly wove the cloth and sold it to other masters. Within this structure everybody, so they imagined, was independent. That they were subject to recessions, and could be thrown out of work, either escaped them or they later forgot. What everybody did have, and certainly remembered, was the freedom to impose their own tempo on life.

In the 1770s everything changed. A burst of mechanical inventions meant that high quality cotton could be produced in hitherto unimaginable quantities. It was because the initial inventions were connected with the cotton trade that Lancashire became the world cradle of the Industrial Revolution, suffering from the incalculable pressures of being first in the field. At the start there was an insatiable market, both at home and abroad, for this splendid, cheap material. Capital poured into Manchester. Shillings turned overnight into massive fortunes. Small-time masters became manufacturers and in the process grew further and further away from the men with whom they had hitherto worked amicably. Chasing their pot of gold, or at least better wages than they could earn as joiners, hatters and locksmiths, butchers, bakers and candlestick makers, the people poured in too. The stampede turned Manchester from a fair sized town to the second largest city in England. Manchester and Salfords joint population of 40,000 in 1750 had risen to 95,000 by 1800. It turned the sleepy villages into cotton towns. Oldham with less than 4,000 inhabitants in 1750 had grown to 12,000 by 1800. The whole area resembled a new-found colony, called Eldorado.

However, by the time John Lees was born the cotton bandwagon was running off the rails. England was at war with France, and the longer the wars dragged on, the more erratic its course became. The boom days when spinning families were earning between 30s and 40s a week, and those involved in weaving averaging between 40s and 60s, became memories told by father. And grandfather started to recall the good old days before mechanization. For if wages were plunging downwards and unemployment, with the new concentration of people dependent on a single manufacture, was becoming mass, other forces could not be checked either. Industrialization had changed the structure and tempo of life irrevocably.