Table of Contents

First published in Norwegian as En norsk tragedie Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AS, 2012. Norwegian edition published by Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AS, Oslo. Published by agreement with Hagen Agency, Oslo, and Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AS, Oslo.

This English edition Polity Press, 2013

English Translation 2013 Guy Puzey

The right of Guy Puzey to be identified as Translator of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This translation has been published with the financial support of NORLA.

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-7220-5

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-8002-6 (epub)

ISBN-13: 978-0-7456-8001-9 (mobi)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: www.politybooks.com

Preface

A year ago today, on 24 August 2012, Anders Behring Breivik was found guilty of killing seventy-seven people, violating sections 147 and 148 of the Norwegian Penal Code, which cover acts of terrorism, and section 233, premeditated murder where particularly aggravating circumstances prevail. The prosecuting authority's plea that he be transferred to mental health care was not upheld. The court found Breivik criminally sane and sentenced him to preventive detention for twenty-one years.

Thus a chapter came to an end. The events of 22 July 2011 had not only been scrutinized in detail by possibly the most comprehensive court case in Norwegian history, but had also been thoroughly investigated by the 22 July Commission and almost endlessly discussed in the media. Nevertheless, there are still aspects of the case that have not been reported widely. The extent of the detailed discussion has perhaps also meant that the bigger picture has become fragmented. How can we understand 22 July 2011?

A single book cannot describe such a great tragedy, but a book can still go into further depth than an article or a television programme and attempt to create a narrative or analysis of the events. Ideally, then, a book may contribute to deeper understanding.

My work on this book took other routes than I had initially envisaged. I eventually encountered the dilemma of how much I should tell and where to draw the line. I made a different choice from most Norwegian journalists because I decided that some of the lesser-known elements shed light on the explosive hatred that had such deadly consequences. They have explanatory power.

This was not a simple assessment; rights came up against other rights. Those affected have the right to know as much as possible about the background to the catastrophe. Breivik and his family have the right to their privacy. With a case of such enormous dimensions, however, I concluded that openness weighs heavily as a consideration. This is why I chose to tell more about Breivik's background and family than was publicly known at the time, because the picture I would have painted otherwise would have been incomplete at best, if not false.

That decision left its mark on this book. I have written about the community that was attacked, AUF [the Workers' Youth League], and, in a broader sense, Norway. I have written about extremist reactions to the emerging new Europe, with a focus on Breivik's so-called manifesto. I have learnt a lot in the process. The events of 22 July showed that Norwegian society is strong, but also that some people are left out of it. The reasons for this are not always clear, including in this case.

The process of understanding what led to Breivik becoming such a radical outsider is important. Without knowledge of where the holes in the net of our society are to be found, it is difficult to mend them. On its publication in Norway in the autumn of 2012, this book caused a debate about writers' ethics and the roots of radicalization.Why do children from peaceful and prosperous societies end up as terrorists? While Breivik serves his possibly lifelong sentence, the discussion about the attacks on 22 July 2011 and the phenomenon of European terrorism continues. I believe that is a good thing, and this book is a contribution to that discussion.

Aage Borchgrevink

Oslo, 24 August 2013

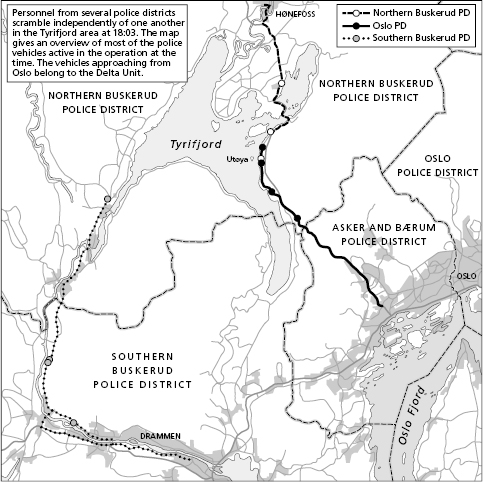

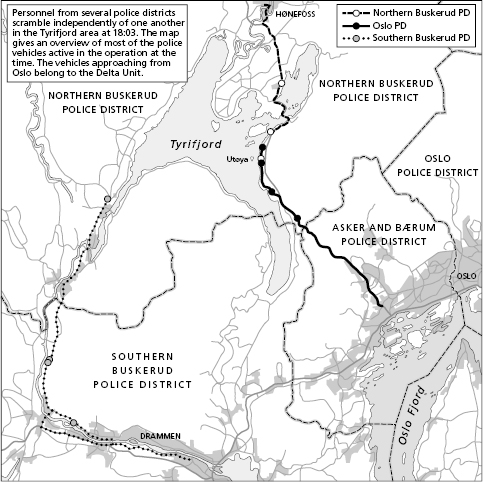

The Tyrifjord and surrounding area, 22 July 2011

Redrawn from Rapport fra 22. juli-kommisjonen [22 July Commission Report], Report for the Prime Minister, NOU 2012: 14, fig. 7.3, p. 118.

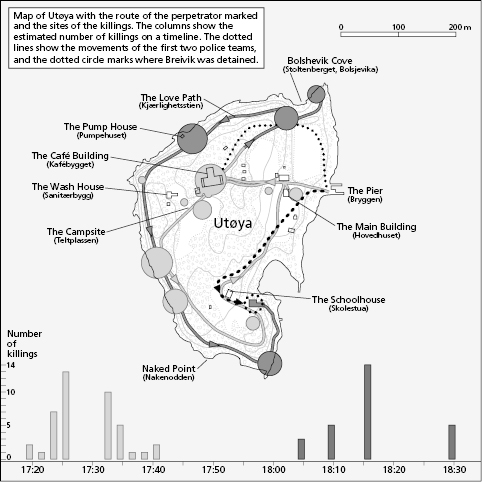

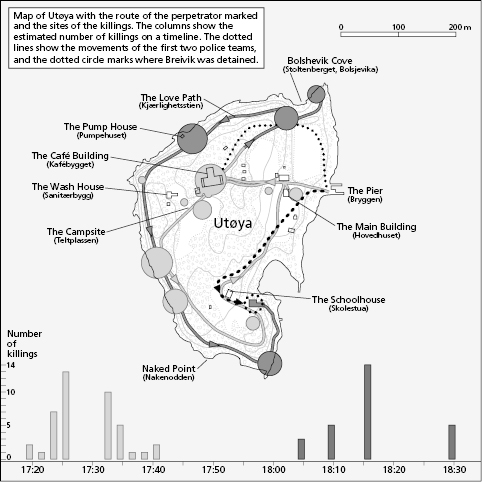

Utya

Redrawn from Rapport fra 22. juli-kommisjonen [22 July Commission Report], Report for the Prime Minister, NOU 2012: 14, fig. 7.5, p. 120.

The Explosion

The bomb exploded at 15:25:22. The blast reverberated through the city. The van disintegrated. A motorcyclist and a chance passer-by vanished in the white flash of the explosion. A fierce fireball blinded the nearest surveillance cameras and was followed by a cloud of smoke and dust. Pieces of the van flew like projectiles in every direction, axles and engine parts spinning through the air.

At the scene, cars were flung around, and the lamp posts bent like blades of grass. The buildings on both sides of Grubbegata bore the brunt of the shockwave, completely destroying their lowest floors. The pressure wave pulverized the windows in the floors higher up, passed right through the building and smashed glass in other buildings around the square in front of the high-rise H Block. Ceilings collapsed above the offices in the H Block and in the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. Splinters of glass and wood whistled through the corridors and offices, drilling their way deep into wall panels and cupboards.

The blast sparked fires on both sides of the street and gouged holes in the asphalt. The bomb crater gaped open right through two levels of tunnels running under the street. These corridors were used to transport documents between the ministries. The explosion cut deeply, uncovering hidden passageways and exposing the very nerves of administration in Norway. There was a smell of sulphur, like rotten eggs.

Eight minutes earlier, at 15:17, the large, white Volkswagen Crafter van had turned in off the street called Grensen. It drove calmly up Grubbegata towards the government district and stopped on the right-hand side in front of a metal fence covered with a white canvas to hide the construction works outside R4, the building that housed the Ministry of Trade and Industry as well as the Ministry of Petroleum and Energy. The driver put on the hazard lights, as illegally parked vans often do, and made his final choice.

Next page