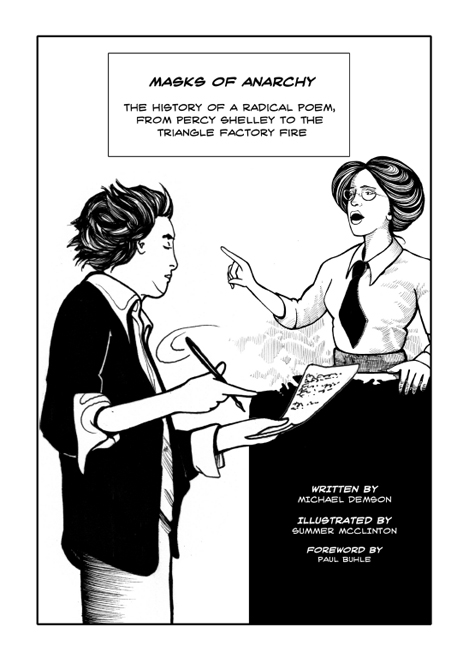

First published by Verso 2013

Text and preface Michael Demson 2013

Artwork Summer McClinton 2013

Foreword Paul Buhle 2013

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

eBook ISBN: 978-1-78168-229-6

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

v3.1

FOR AUDREY

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

PAUL BUHLE

COMICS MEET HISTORY, AND POETRY, TOO!

The book before you, reader, is one of the most remarkable works of comic art to date. One can safely predict that Masks of Anarchy will cast its influence widely over future nonfiction graphic work, especially as regards the uses of poetry and the meanings of social, labor and womens history.

Scholar Michael Demson and artist Summer McClinton have mediated betweenand in one or two ways actually mergedthe saga of the great English revolutionary poet Percy Shelley and the story of courageous immigrant labor activist Pauline Newman, who stirred working women into action, in part through the use of Shelleys work and legacy. An amazing true-life tale in itself, the combined version is memorably captured here both in narrative and art. Shelley and Newman come alive equally for us, their fates taken together with the poetic lines offering proof and promise of the human capacity to dreamand to act.

We need to appreciate this book within the field of comic art,and in particular the evolution of nonfiction comics. Speaking as an editor of nearly a dozen of these works and a scholar of the field at large (in the English language), I hope a small history lesson will remind readers how very much has changed in a short time with the acceleration of developments in comic art and narrative, and how best to appreciate the text in hand.

We might most effectively begin near the chronological end: the first decade of the new millennium has seen more significant developments in comic art than any time since the first comic strips appeared, in the dailies of the 1890s. Now, of course, comics as well as their artists and readers are found all over the globe, both in print and on the Internet. From a visual standpoint, todays comics are inspired and shaped by a contemporary readership that is not only substantially larger than in the past, but also arguably more aesthetically sophisticated than its predecessors in the reading of the comics.

As late as 2000, the nonfiction component (a microscopic corner of the so-called graphic novel world) would have seemed most unlikely to grow much or to make an impact. How it has since done both is a story wound around a larger comic art history, which has gained more facets but also more clarity than one could have imagined only a decade or so ago. Comics have now become a full-blown field of scholarly inquiry, as numerous scholarly journals and books have vanished in their earlier forms to be replaced by electronic versions, and as comics scholars themselves gain status in the universities. This marks either a fitting irony or a kind of fulfillment of the art form.

THE RECEDING PAST

The field of comic art, always subject to volatile market conditions and very often to a boom-and-bust pattern, with surges followed by collapse, has advanced so unpredictably that almost nothing seems far in the past. Newspaper comic favorites like Blondie have notoriously refused to die or retire with their creators, continuing over generations with one imitator after another. With most of the strips, the less famous have disappeared from public memory, but classic reprint volumes of past comic art began to appear in large numbers during the 1970s-80s, a trend that has only accelerated. The presence of the Internet, with less strict copyrights (or less attentive enforcement), has added enormously to the volume and variety of comic art readily available.

And yet artistic innovations have in some respects been historically quite slow as well as idiosyncratic. Harvey Pekar once quipped that the art of comic art has been so limited that the modernism that transformed the very nature of painting during the 1910s-20s only reached American comics during the 1970s-90s. Even then, these advances of artistry appeared highly avant-garde, almost shocking, and doubtless unwanted by legions of superhero-trained, juvenile-mentality readers. Not only had the parameters of style and narrative been narrow, but outside of the daily press, in comic books, trends like war, horror, and love-interest comics tended to come and go in a rush, along with the bulk of the smaller publishers themselves. Rare were the individualistic talents with the time and the encouragement to grow to their full potential. Rarer still were those artists who could make a living on such experimental efforts.

Still, even the earliest comics of the 1890s offered hints that they might be at last understood and appreciated a century and more later. The discovery of a potentially massive daily readership with a taste for a new kind of illustration prompted the onset of comic strips as a major commercial art form of the fin de sicle, evolving within a generation or two into most of the modern versions that readers recognize today. How was it that the barely literate newspaper readership of the 1890s-1920s, obviously craving visual humor and drama, sought images of themselves (or of those distinctly unlike themselves), in art, or at least a kind of art, hitherto unknown?

Were comics on the funny pages perhaps simply easier, cheaper, to access than a vaudeville stage or the first movies? Did the family comics readerthat is, presumably the middle-class reader of influential, slow-moving domestic dramas like Gasoline Alleyof the 1920s and after also go to art galleries? How did things change with the sudden emergence of the hugely popular comic book format, aimed squarely at the young (and mostly boys)? Such questions and others were first posed by scholars around 1960, part of the growing academic interest in mass culture that emerged alongside an actual decline in the circulation of comic books and a reduction, in various ways, of innovation and actual space for the more artistic newspaper strips. Decades late in even being posed, these were the very questions that the next generation asked a second time in the aftermath of the next phase, the rise and fall of uncensored, openly radical Underground Comix. A quipster of the 1970s remarked that for Parisian graduate students before 1968, writing a dissertation on comic art was impossible, impermissible, but after the student revolts, became irresistible, albeit there were few in actual numbers. The generation or so of professors that followed actually used comics as illustrations in their presentations, and increasingly assigned comic art to students bored with the normal reading matter.

Until such graphic novel courses in colleges and universities placed comic art on bookstore racks alongside manga titles, only a small handful of comic artists had gained serious recognition. Art criticism, let alone art history, in this field was still waiting to be born. The majority of published comics scholars, the writers of monographs, has to date continued to consist mostly of self-taught non-academics. Even the academic scholar writing commentary aims mostly at an audience of fellow fans, usually providing texts with as many illustrations as possible on oversized pages.