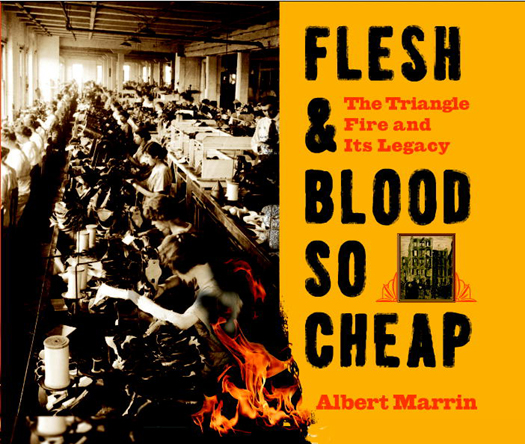

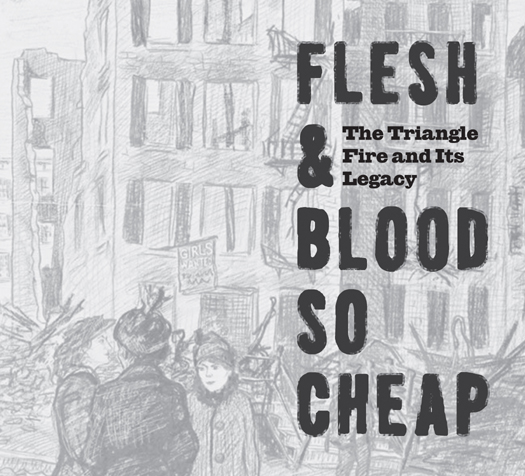

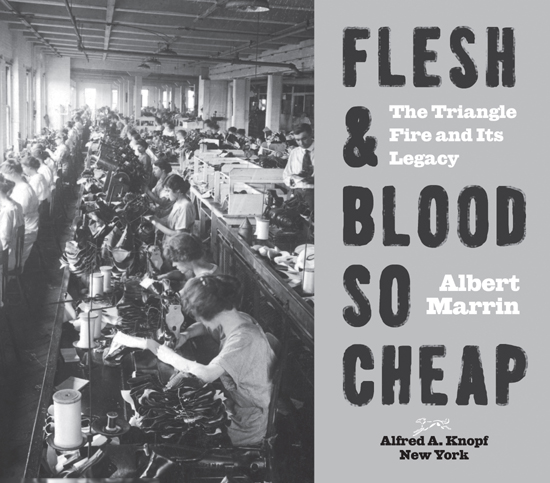

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Text copyright 2011 by Albert Marrin

Main jacket photograph copyright by FHP/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Inset jacket art by Henry Glintenkamp, 1916

Jacket photograph of flames by Shutterstock

For picture credits, please see .

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Random House Childrens Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Visit us on the Web! www.randomhouse.com/kids

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at www.randomhouse.com/teachers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Marrin, Albert.

Flesh and blood so cheap : the Triangle fire and its legacy / Albert Marrin. 1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-97660-4

1. Triangle Shirtwaist CompanyFire, 1911. 2. Clothing factoriesNew York (State)New YorkSafety measuresHistory20th century. 3. Industrial safetyNew York (State)New YorkHistory20th century. 4. New York (N.Y.)History18981951. I. Title.

F128.5.M122 2011

974.71041dc22

2010021533

Random House Childrens Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

v3.1

to their memory

The land flourished because it was fed from so many sourcesbecause it was nourished by so many cultures and traditions and peoples.

President Lyndon B. Johnson

at the Statue of Liberty,

October 3, 1965

IV. An Overflow of Suffering: The Uprising

of the Twenty Thousand

PRELUDE

From the ashes of the Triangle Company fire began to rise one of the most dramatic and far-reaching [changes] in American historyone that would eventually redefine forever the role the government played in the lives of ordinary people.

Ric Burns and James Sanders, New York (1999)

New York City, Saturday, March 25, 1911. One of those sparkling early-spring afternoons New Yorkers so enjoy after a cold, dreary winter. Under the cloudless blue sky, strong, bracing gusts of wind blew across Manhattan Island from the East River. The air smelled fresh and clean, and it felt good to be alive. It would also be a day of tragedy that would weigh on the hearts of witnesses and survivors for the rest of their days.

People flocked to Washington Square, a ten-acre park named for our first president. A century earlier, the site was a wasteland on the citys northern outskirts. Back then, it served as a cemetery for unclaimed bodies and the poorest when they died; even today, the bones of some twenty thousand people lie under its lawns and paths. After the cemetery closed in 1825, a group of elegant town houses called the Row rose on the north side of the square. This area lay in the country, and the rich spared no expense to escape there from the bustling city. Although the Row still exists, by 1911 Washington Square had become a green oasis amid grimy factories and immigrant neighborhoods.

The Row along Washington Square in 1936.

On this Saturday, families from the tenements strolled the tree-lined paths. Children ran around, played on the grass, or stood on the playground swings and flew to the moon. Lovers walked hand in hand. Students from nearby New York University sat on the benches reading, thinking great thoughts, arguing, flirting.

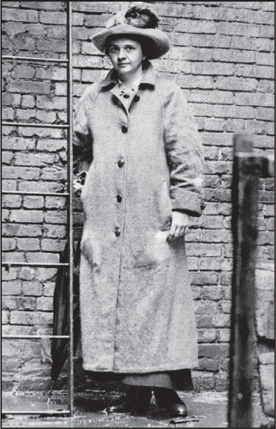

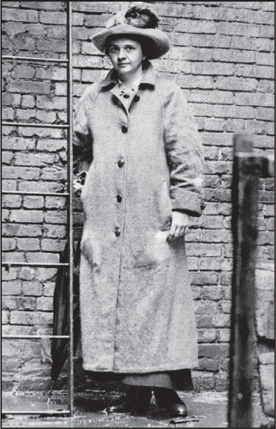

Miss Frances Perkins, thirty-one, was visiting a friend at her home in the Row. A social worker by profession, Perkins led the Consumers League, an organization devoted to improving working conditions in factories. The two women were about to have tea when they heard fire engines. Opening the front door, they saw smoke rising behind a New York University building across the street from the east side of the square. The top three floors of an adjoining ten-story building at the corner of Washington Place and Greene Street were ablaze. These floors housed the Triangle Waist Company, a manufacturer of shirtwaists, a kind of womens blouse that was at the height of fashion.

Hearts pounding, the friends ran across the square, joining the crowd racing toward the smoke. Moments later, they came upon a scene that seared itself into their souls. By twos and threes, workers, some with their hair and clothes on fire, were jumping from the

Within minutes, 146 workers died, broken on the sidewalk, suffocated by smoke, or burnt in the flames. Most were young women ages fourteen to twenty-three, nearly all recent immigrants, Italians and Russian Jews. Dubbed the Triangle Fire, for ninety years it held the record as New Yorks deadliest workplace fire. Only the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center took more lives.

Frances Perkins, circa 1911.

Frances Perkins was shaken by what she saw that day. It was a life-changing experience. The sight of people jumping from windows affected her so deeply that she vowed such a horror could not, must not, be allowed to happen again. She would devote the rest of her life to making her vow a reality. Yet the Triangle Fire is more than a tragedy. It is part of a larger story, one woven into the very fabric of American life. Without understanding that larger story, we cannot fully understand the disaster and how it influences us today.

Fifth Avenue, an area of wealth and luxury in New York City, circa 1900.

The Triangle Fire occurred during the greatest mass movement of people in history. People leave their homeland for various reasons, or pushes, as historians call them. Pushes include natural disasters, crop failures, poverty, war, persecution, or simply the desire for change. Those who leave go to places they think will offer a better, happier, more interesting future. We call such reasons pulls. Thus, in the years 1870 to 1900, about twelve million immigrants arrived in the United States, nearly all from Europe. During the next decade, 190110, another nine million75 percent of the total of the previous three decadesreached our shores. Most of these entered through New York City.