ALSO BY ROBERT REID

The Spectroscope

Tongues of Conscience: War and the Scientists Dilemma

Marie Curie

Microbes and Men

My Children, My Children

Land of Lost Content

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781473554771

Version 1.0

Published by Windmill Books 1989

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Copyright Robert Reid 1989

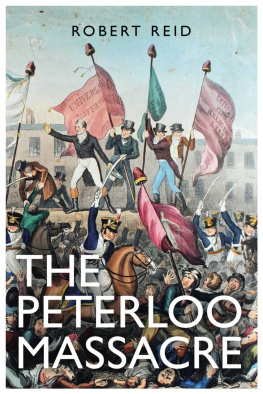

Cover image Bridgeman Images

Robert Reid has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

First published in Great Britain in 1989 by William Heinemann

This digital edition published in 2017 by Cornerstone Digital

Reissued in paperback in 2018 by Windmill Books

Windmill Books

The Penguin Random House Group Limited

20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London, SW1V 2SA

www.penguin.co.uk

Windmill Books is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9781786090409

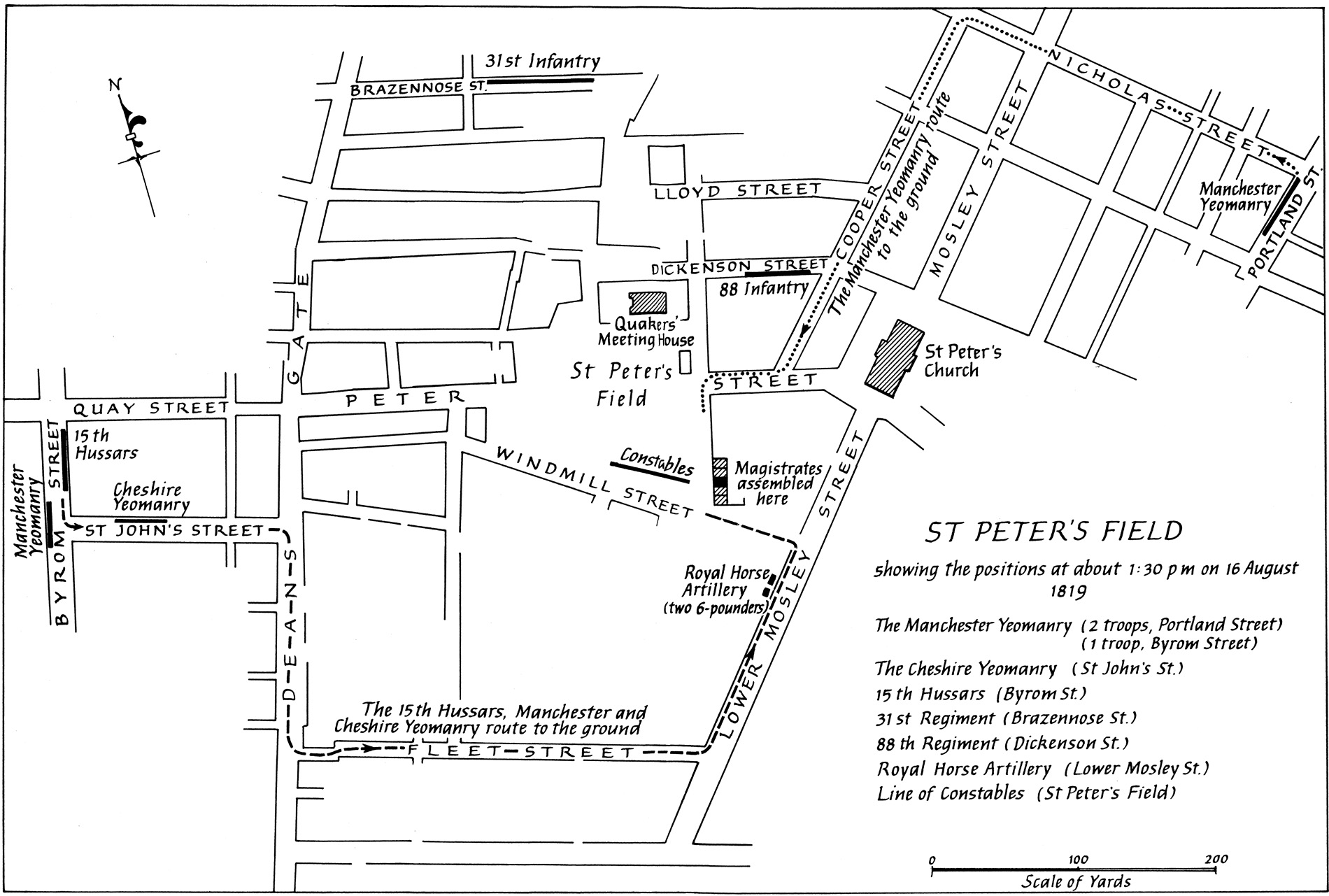

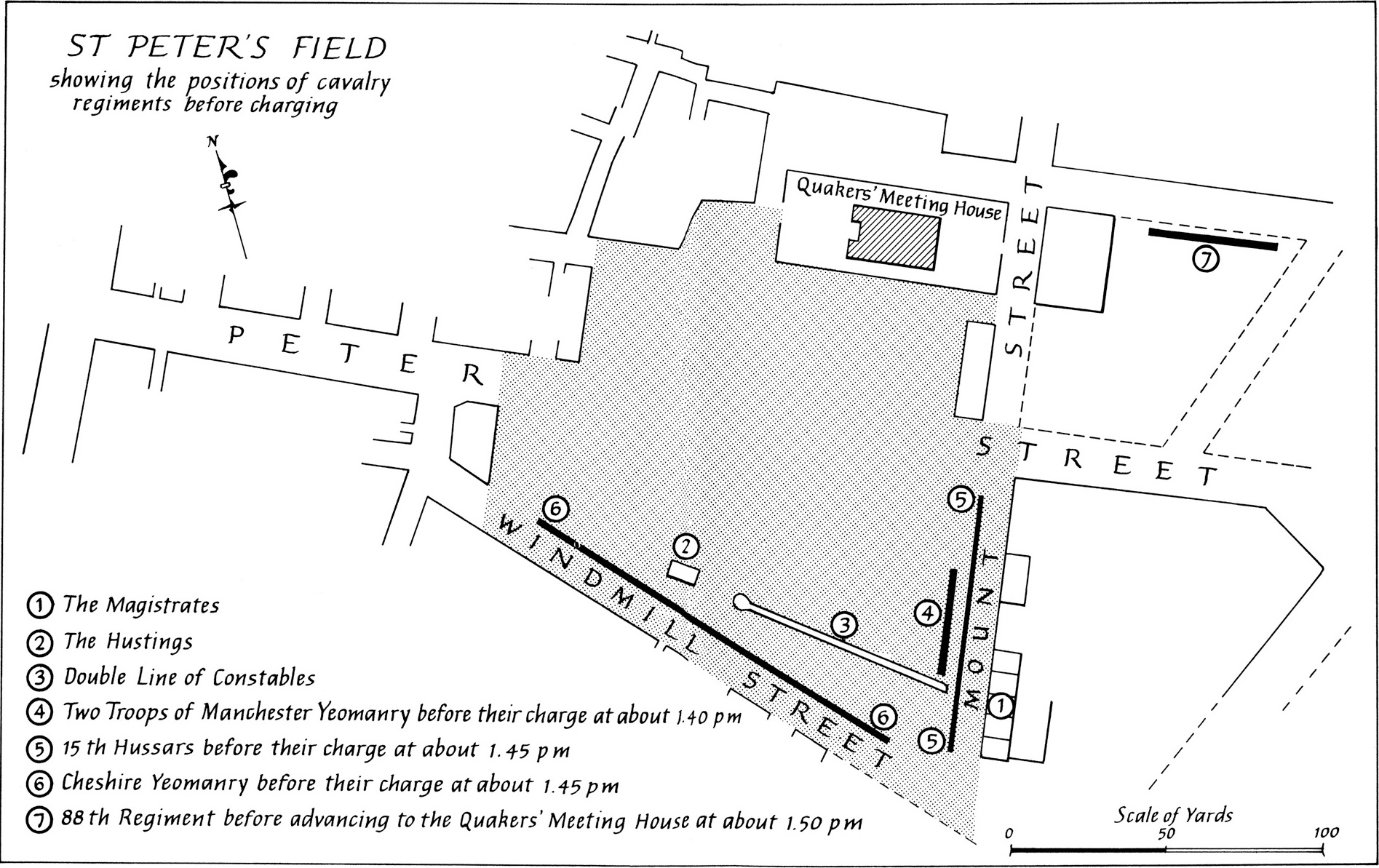

MAPS

INTRODUCTION

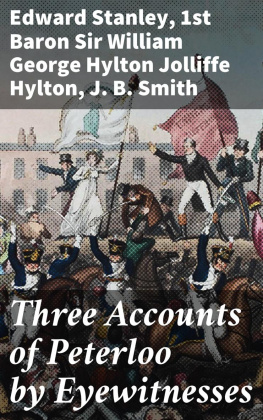

The conflict at the focal point of this book is a unique incident which stains the long path leading to the emancipation of the people of Britain. The name Peterloo is well-known, but what it involved is becoming less familiar to successive generations. The intermingling of characters involved in the Luddite Revolt with those intimately concerned with Peterloo provided a sure guide to the contemporary sources; these supply key evidence of the events leading to the Massacre. In chronicling these events I have laid emphasis on the critical role played by technological change. In parts, I have repeated some ideas concerning technology and its signal power from a previous book, Land of Lost Content, which dealt with the Luddite Revolt. I have done this because I believe these ideas are important to an understanding of the conditions leading to Peterloo, and the lessons to be learnt from it and, no less, to an understanding of the problematical forces shaping our present civilisation.

I am deeply in the debt of J. E. Stanfield for his invaluable advice which helped shape my manuscript. Equally, I must thank Dr Robert Glen, not only for his informed comments, but also for the use I was able to make of his scholarly study, Urban Workers in the Early Industrial Revolution. Of books dealing with events leading to Peterloo, I have found Dr Donald Reads Peterloo, the Massacre and its Background to be the most informative and the most reliable.

I am grateful to the librarians of the British Library, Chester Library, Chester Record Office, Chethams Library, Manchester, Colindale Newspaper Library, Doncaster Borough Council Archives Department, Balby, Doncaster Central Library, Exeter Library, the John Rylands University Library of Manchester, the London Library, Manchester Central Library, the National Horseracing Museum, Newmarket, the Public Record Office, the RIBA, the Royal Institution and Stockport Public Library for the generous help they have all unfailingly given.

1

The Soldiers Return

In the autumn of 1816, the senior British officer who, the previous year, had commanded the second Guards division at Waterloo, stood one day on a beautifully contoured patch of ground above the Norman tower on the edge of an English village and reconnoitred the unhindered view south. He took particular note of the fields to his front leading down to Campsall church, and to the rolling, long-settled countryside beyond. Behind him was a substantial stone-built mansion. From its windows, over its walled gardens, there was a view in every direction as commanding as that which the soldier contemplated. The historic name of the hill, Campsmount, described adequately enough the sites military potential.

The general, Sir John Byng, had had a military career which had not been short of either experience or incident. He had many times served under Wellington, had been wounded more than once in military encounters, had on one occasion in the Peninsula in 1813 personally charged through to plant the colours of the 31st Regiment behind enemy lines, and had been knighted before he even reached the field of Waterloo.

The modern visitor to Campsmount can still extract from the view but with difficulty what so engrossed Byng. The generals aspect to the south was one of unblemished rural beauty. But today, there is a striking addition. Some distance beyond the patchwork fields of corn and grass still descending to the Norman church tower, rises an incongruous hulk: a prominent red-brick Victorian scab to which, over many years, have been added vast asbestos-clad structures, warehouses, winding gear and coal shutes. This is the coal mine at Askern. The nineteenth-century South Yorkshire town of the same name which spread as the pits productivity grew, stands alongside, its houses in the new smokeless age, no longer pushing out the coal fumes which for decades blackened their walls.

The panorama from Campsmount provides a vivid example of how the demands of nineteenth-century technology overwhelmed both the rural English landscape and its economy, enriching the nation and transforming forever the way of life of its inhabitants.

The purpose of General Byngs visit to this hillside, paradoxically, was to discover a place where he could be sure to be free of the sight which today assaults the visitor. He had just come from a district where the dominant image that of the process of the transformation of Britain was too evident and too brutal to his sensitivities. In 1816, from this South Yorkshire vantage point, any sign of the metamorphosis was invisible. And the fact was, that the indisputable military advantages and defensive capabilities of Campsmount were of no interest whatever to him. Still fully employed as a lieutenant general in an England no longer at war, he had come temporarily at least to seek his personal peace here.

The eighteenth-century mansion behind him was owned by the Yarborough family and was to be let, fully furnished, along with its Manor Garden, Pleasure Ground, farmyard and buildings for 150 per annum. The surrounding 400 acres of high quality farmland were also being offered for a further 400 and additional acreage could be made available when required. Costly as these sums were, the farming prospects presented by such an estate with such excellent corn and root-crop potential were considerable. John Byng, who most certainly needed to augment his military pay, estimated the business possibilities of Campsmount very favourably.

There was, however, one further highly desirable quality of the site which made him look on it with an even keener eye. Byng was the owner of an expensive and obsessive habit. Scarcely a better place could be imagined in which to indulge it than here.