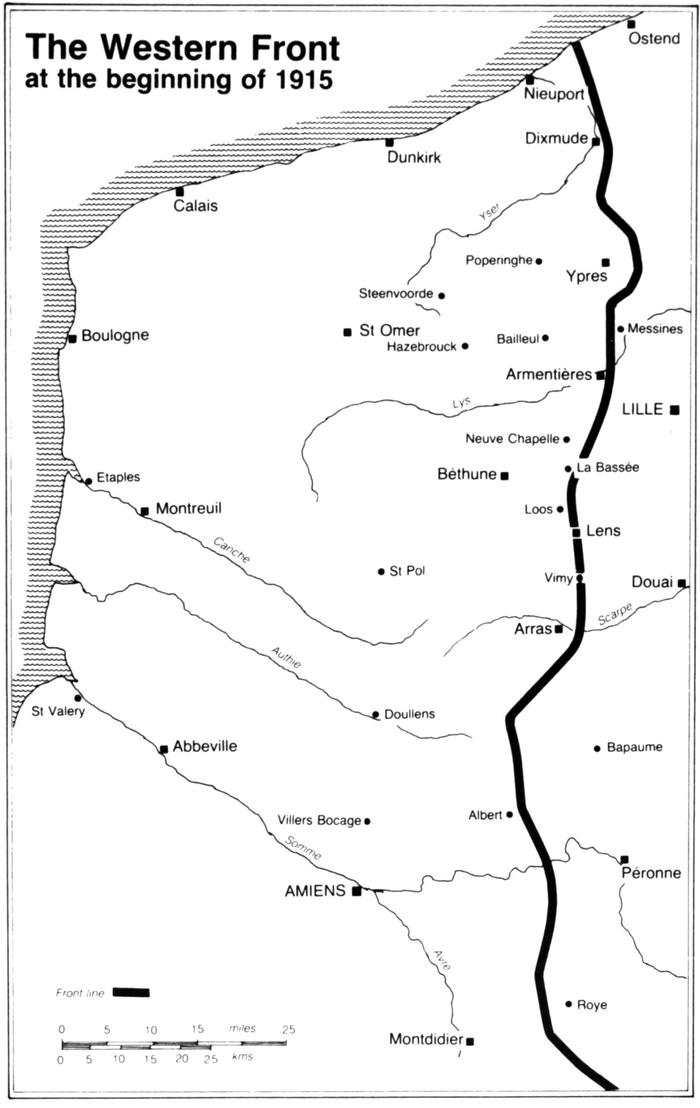

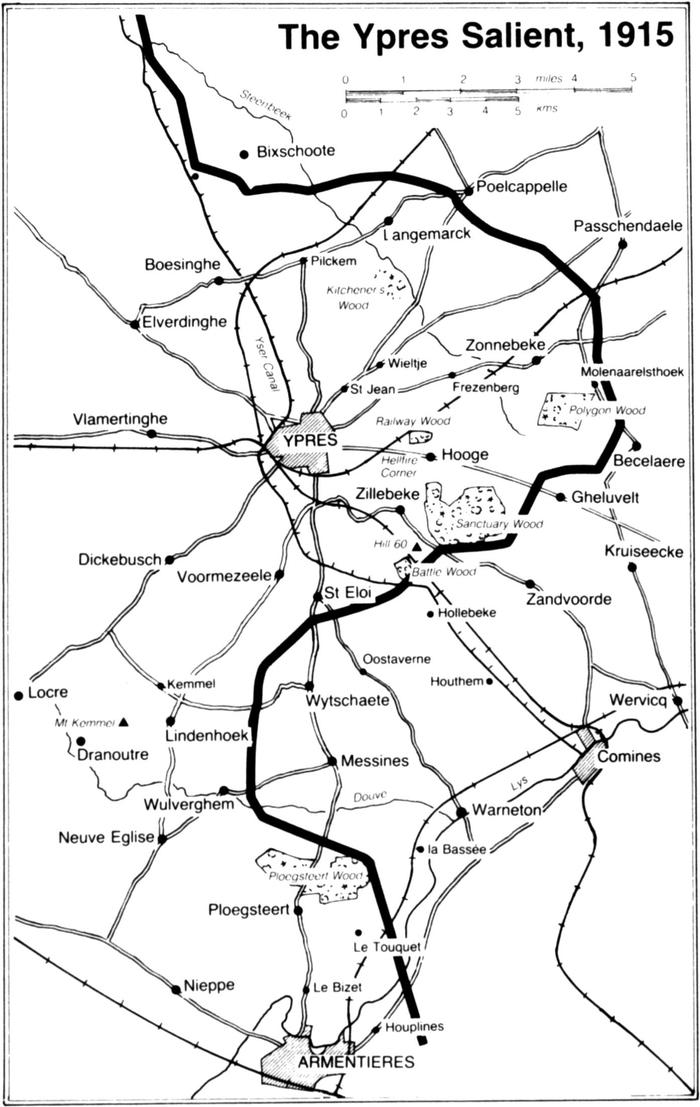

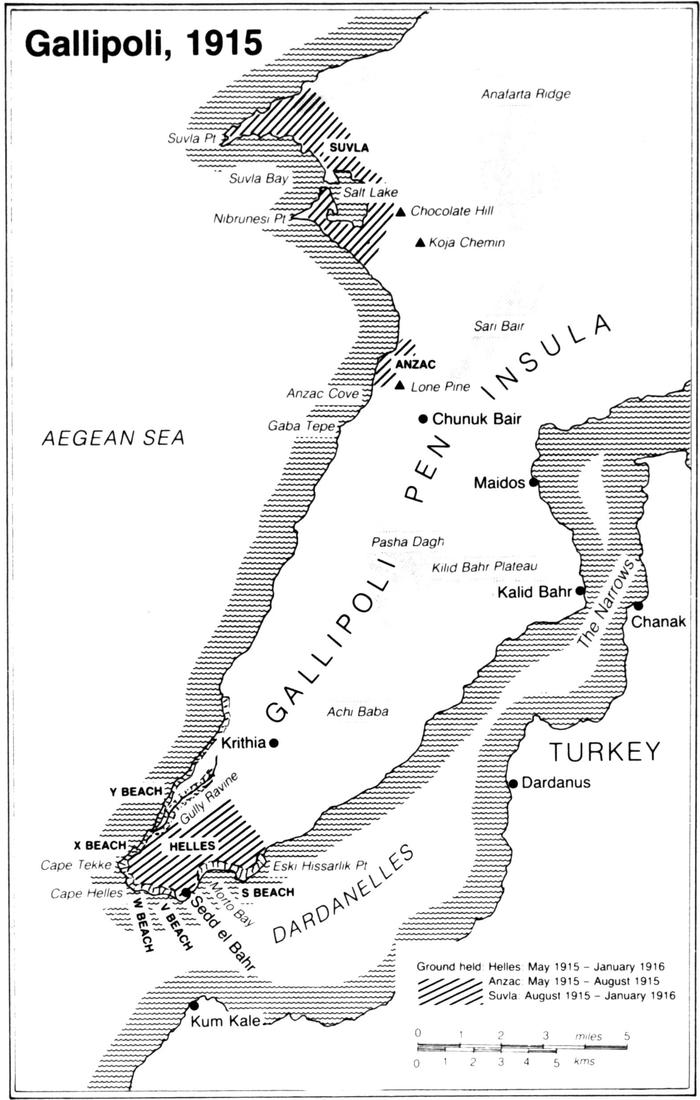

It is doubly surprising that George Ashurst has written of his service in the Lancashire Fusiliers during the First World War. In the first place, it is usually officers or middle-class men serving in the ranks by preference or circumstance who have left written accounts of their experiences. There are, it is true, several exceptions most notably the marvellous Frank Richards but it remains true to say that well observed first-hand accounts by working-class soldiers are relatively rare. And, as the opening chapter so clearly demonstrates, George Ashurst came from a working-class background typical of that of so many of the soldiers who fought in the First World War. Secondly, the odds against Ashurst surviving to write were almost impossibly high. The fortune of war put him in the path of a German gas attack at First Ypres, ashore on Gallipoli, and over the top on the first day of the Somme. Not only did he survive these pitched battles, but he also bore months of trench warfare across the whole length of the British sector of the Western Front, as well as in Gallipoli, and took part in a dozen or more grim and dangerous trench raids and patrols in no-mans-land. In the process he did indeed earn two Blighty ones but he was lucky not to share the fate of the 13,642 Lancashire Fusiliers who perished during the war.

George Ashurst wrote the bulk of his memoirs (though not the section dealing with his childhood and youth) from diary and memory in the 1920s. This fact has two important consequences. In the first place, Ashurst was often unaware of the accurate details of the events in which he participated. It is temptingly easy for historians to regard the first-hand accounts written or oral of survivors as the pure and undiluted truth. Such is rarely the case. Even when events are recalled shortly after they have happened, memory still plays tricks, with snatches of experience being collated in a haphazard order, like clips of film assembled at random from the cutting-room floor. There is a natural tendency for the mind to shut off the most ghastly episodes, and the stress of battle itself interposes a filter between an event and its observer. Lieutenant Geoffrey Malins, who filmed the British attack on Beaumont Hamel on the first day of the Somme, described the process well:

The noise was terrific. It was as if the earth were lifting bodily and crashing against some immovable object. The very heavens seemed to be falling. Thousands of things were happening at the same moment. The mind could not begin to grasp the barest margin of it all.

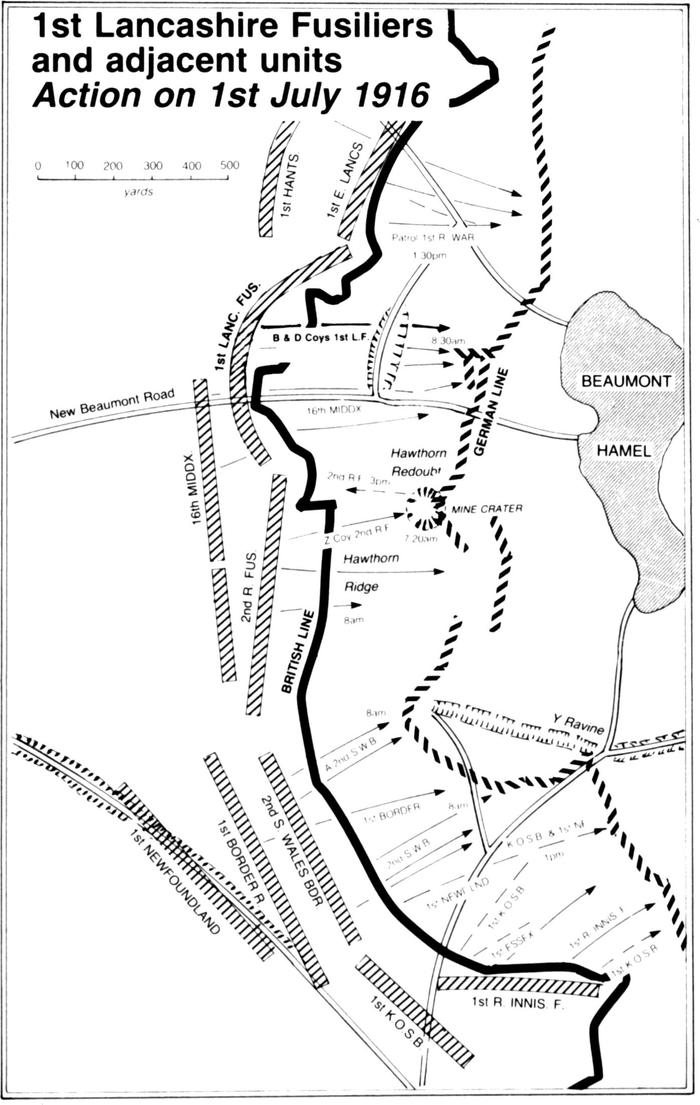

And there are other problems. Most front-line soldiers in most wars live on a diet of rumour intermixed with partly explained facts. During the First World War an understandable desire to preserve secrecy coupled with a tendency for information not to filter its way right down the chain of command to the non-commissioned ranks meant that private soldiers and NCOs (and, indeed, a good many officers) often had only the haziest idea of the progress of the war outside the narrow frontage of their own battalion or even their own company. Rumour made up for the shortage of hard facts, and rumour often coalesced to assume the status of truth in the minds of survivors. Ashurst is consequently in error on several points of detail. He believed, for example, that the mine beneath the Hawthorn Redoubt was blown at 7.30 on the morning of 1 July 1916, and that its explosion was the signal for the assault. He also transposes his battalions tour of duty in the Nieuport sector in 1917 with its time in the line north of Ypres in the winter of 191718. Ashurst could have corrected these facts by checking them against a regimental or official history, but in the process much of the freshness of his account might have disappeared. Moreover, what soldiers believed to be the case is often as interesting as the objective but bald fact which emerges from official records.

This caveat leads naturally on to the second consequence of the way in which Ashurst wrote. The attitudes he describes are essentially those of the working-class Englishman of sixty years ago. Authority was accepted instinctively, even when those wielding it were disliked. Ashursts comrades complained frequently as British soldiers tend to. They muttered when being given a pep talk by their divisional commander on the eve of the Somme, and gave vent to horrible wishes and curses when pushed along on the march by the comfortably mounted adjutant. But they kept going. Ashurst makes no secret of his contempt for shirking amongst the officers, but is always prepared to give credit where it is due: he describes one gallant young officer trying to force panic-stricken men to stand and fight at the point of his revolver. He admired bravery wherever he saw it, and the picture of a signaller springing up onto the bank of the sunken road in front of Beaumont Hamel, only to fall back riddled with bullets, remained engraved on his memory.

Ashursts comrades were certainly no angels. They drank to excess when the opportunity offered many were the worse for drink when their battalion left the regimental depot for war. He describes a brothel in Armentires, its tables swimming in cognac and vinblanc, with a queue on the stairs, where the boys did their best to stand upright when the padre arrived to rebuke them. Valuable items with no clearly identifiable owner were liberated; Ashurst gives one lively description of the sergeants in his company carrying out a successful tomb-robbing raid by night.

Like so many front-line soldiers of the First World War, Ashurst reveals no particular hatred for his enemy. He was glad of the truce of Christmas 1914, and complains bitterly of the comfortably housed and well fed Heads in the rear who started the war again. The Germans are Fritz and the Turks Johnny Turk, and there is no evidence of resentment towards either. Far from it: on one occasion, when burying a good-looking lad, he took care to place a photograph of the dead Germans family next to his heart, and on another he and his comrades refrained from firing on a German who was too brave to die. Nevertheless, Ashursts lack of any feeling of personal antipathy did not prevent him from doing his duty. He got closer to the German front line than most of his comrades on 1 July 1916, and the frequency with which he was selected for patrols bears testimony to his fighting spirit. He was promoted steadily through the non-commissioned ranks, and was completing his training for a commission when the war ended.

Yet it was not lofty motives that kept him in the trenches; indeed, he admits that he might have considered malingering or desertion, but the former was foreign to his nature and the latter would have shocked his family. There were times when he clearly considered that he had done his bit, and on one occasion he told his company commander so in as many words. He was glad of his Blightly ones, and accepted the offer of a commission because he agreed with his men that it was a glorious opportunity while I was away for my instruction the war might finish. But there was an innate conviction that the allies must win; that sneaking away [from Suvla Bay] like a thief in the night was wrong; that to hold on grimly, suffering heavy casualties but losing no ground was the right way to behave.