WITH WINSTON CHURCHILL AT THE FRONT

Winston in the Trenches 1916

First published in 1924, under the pseudonym Captain X, by Gowans and

Gray Ltd., London and Glasgow.

This extended edition published in 2016 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS.

Copyright Major Andrew Dewar Gibb MBE, QC, LLD, MA, LLB

The right of Major Andrew Dewar Gibb to be identified as the author of this

work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-84832-429-9

PDF ISBN: 978-1-84832-432-9

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84832-431-2

PRC ISBN: 978-1-84832-430-5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in

or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any

means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise)

without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does

any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal

prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

For more information on our books, please visit

www.frontline-books.com,

email

or write to us at the above address.

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Typeset in 11/13.25 Garamond Book

Contents

Part II

With Winston Churchill at the Front

Chapter 16 Following in Churchills Foosteps:

A Visitors Guide to Plugstreet

Publishers Note

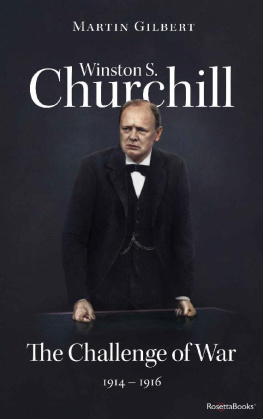

The publishers wish to acknowledge the assistance provided by the following individuals: Allen Packwood, at the Churchill Archives, Churchill College, Cambridge, for all his advice and allowing access to the Sinclair and Churchill correspondence; Alison Metcalf, the Curator of Missionary & Military Collections at the National Library of Scotland, who unearthed Professor Dewar Gibbs papers, which included his diary; Lady Gilbert, who has permitted the reproduction of her brilliant husbands transcriptions of many of Winstons letters, as well as other extracts of his work these, in general, are taken from Volume III 1914-1916 of his unparalleled study Winston S. Churchill; Paul Courtenay, whose unsolicited offer to proof-read the manuscript was particularly welcome; Katherine Barnett and Sophie West at Chartwell, who provided photographs of items from Winstons time at Ploegsteert; Mrs Wendy Bellars, the Head of Queen Victoria School, Dunblane, and her personal assistant, Clare Rankin, who supplied a copy of Winstons painting which is held at their school; Second Lieutenant Cameron Marshall Veal USAF for his assistance with the research; Francis De Simpel, Anny Beauprez and Matthieu Wulstecke, from Ploegsteert, for sharing their detailed knowledge of their local area; and Patricia Dewar Gibb for her invaluable contribution.

Foreword

I n writing this foreword I must start by saying how delighted the Churchill family is that this remarkable book is being republished. There have been many books written about my great-grandfather, but this one is special. We hear and read so much about Churchill the statesman, the inspirational figure who led the nation and the Commonwealth to victory in the Second World War, but little is said about him during his brief spell away from politics in 1915/16 during the first World Crisis. The author, Dewar Gibb, served with Churchill in the trenches during the First World War; his account shows that Churchill could practise what he preached and that, away from the public arena, was a brave and inspiring leader of men under fire.

I am often asked: What was the making of the man? A large part of his unique character undoubtedly came from his remarkable and dynamic mother, the beautiful Jennie Jerome from Brooklyn, New York City. Another part was formed during Churchills darkest hour: Gallipoli and the Dardanelles disaster. This project was brilliantly conceived from the noblest of motives, for Churchill had written to the Prime Minister, H.H. Asquith: Are there not other alternatives than sending our armies to chew barbed wire in Flanders?

Churchill and the government planned to create a new front elsewhere, to alleviate the wholesale slaughter of a generation on the Western Front; this would lighten the load on the hard-pressed Russians fighting the Turks in the Caucasus, demonstrate to the wavering Balkan neutrals that they should not join the war on the enemy side, and hopefully knock Turkey out of the war. But the Navy could not force its way through the Strait, the military resources did not provide enough troops, and the Turkish resistance was strong. Churchill was obliged to give up his office as First Lord of the Admiralty, to allow the Conservative opposition party to join a Coalition government under Asquith (a Liberal). After six months in a minor cabinet post, he resigned from the government and, as a Territorial officer (he was a major in the Queens Own Oxfordshire Hussars), he reported for duty at the front.

Churchill was made a scapegoat for the Gallipoli debacle. As political head of the Royal Navy, he had done his best to create the conditions needed to enable the fleet to force the Dardanelles. But he held no executive power over the landing of troops at Gallipoli; this was the responsibility of the Secretary-of-State at the War Office, Field Marshal the Earl Kitchener of Khartoum. The situation was Churchills first real setback in a meteoric rise. His wife Clementine later said: I thought he would die of grief.

When he arrived at the front in November 1915, Churchill presented himself to the Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force, Field Marshal Sir John French, whom he knew well, telling him that he was the escaped scapegoat. Churchill was delighted to be assigned by French, for a forty-day period of familiarisation, instruction and experience, to 2nd Battalion, Grenadier Guards: the best school of all. It was not a coincidence that this was the regiment in which his ancestor, the first Duke of Marlborough, had served and later commanded. The commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Ma Jeffreys, welcomed him by saying: I think I ought to tell you that we were not at all consulted in the matter of your coming to join us. Charming! Churchill knew that nothing counted except military rank and behaviour.

After his time with the Grenadiers, French had hoped to give Churchill command of a brigade (four battalions comprising around 5,000 men) and the rank of Brigadier General, which would have counted for a great deal. But when the time came, French had been replaced by Sir Douglas Haig and he and Asquith felt that perhaps he might have a battalion: not 5,000, but fewer than 800 men under command.

The 6th Battalion, Royal Scots Fusiliers had been mauled at the Battle of Loos and subsequent winter service on the Ypres Salient; its members were battered and demoralised. The troops distrusted him and were taken aback to have the politician whom they believed to have overseen the Gallipoli disaster as their commanding officer. Churchills first words to the officers, after staring at each of them out of countenance during an uncomfortable welcome lunch, were: Gentlemen, I am now your commanding officer. Those who support me I will look after. Those who go against me I will break. Good afternoon, Gentlemen. Yet he worked to earn their respect through his decency, hard work, humour and constant bravery. He inspired the devotion of his men in a remarkably short time. He overlooked nothing, taking great pains to gain their confidence: declaring war on lice, improvising baths out of brewery vats and bringing all his influence to bear in order to secure new equipment and clothing, improving the rations, and supervising the creation of a football pitch and arranging matches. He set about improving morale and conditions with customary dedication.