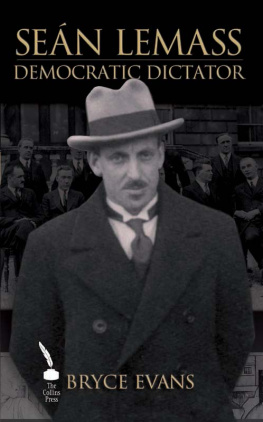

SEN LEMASS

DEMOCRATIC DICTATOR

BRYCE EVANS

www.collinspress.ie

Facebook

Twitter

First published in print format 2011 by

The Collins Press

West Link Park

Doughcloyne

Wilton

Cork

Bryce Evans 2011

Bryce Evans has asserted his moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved.

The material in this publication is protected by copyright law. Except as may be permitted by law, no part of the material may be reproduced (including by storage in a retrieval system) or transmitted in any form or by any means, adapted, rented or lent without the written permission of the copyright owners. Applications for permissions should be addressed to the publisher.

EPUB eBook ISBN: 9781848899414

mobi eBook ISBN: 9781848899421

Paperback ISBN-13: 9781848891227

Typesetting by The Collins Press

Typeset by Carrigboy Typesetting Services

Cover photographs: (main) a young Sen Lemass; (top) first Fianna Fil cabinet, 1932; (bottom): Gabriel Hayes depiction of the Shannon Scheme (courtesy Fionnbharr Riordn).

Contents

To Marian, and my parents

Acknowledgements

I owe a particular debt of gratitude to my good friend, colleague and critic Stephen Kelly; to my father, Peter Evans; to the long-suffering Marian Carey; and to the extraordinary generosity of that fine historian, John Horgan.

My sincere thanks to the following people for their assistance in the course of my research: Lisa, Hugh and Victor at the Military Archives; Rosemary at the Allen Library; Paschal at the Arts Council Archive; Samus, Orna, and all at UCD Archives; the staff of the National Archives of Ireland; of the National Archives of the United Kingdom; of the Fiaich Memorial Library and Archive (in particular Samus Savage); and those who work in the Dublin Diocesan Archive;Trinity College Manuscripts Collection and Early Printed Books Department; the National Library; Dublin City Libraries; the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland; the Irish Newspaper Archive; and the Irish Architectural Archive.

Special thanks to those who allowed me to interview them: Sen Haughey, Ulick OConnor, Michael D. Higgins, Des OMalley, Tony OReilly, and Harold Simms. For their support, encouragement and advice I wish to thank: the straight-talking Diarmaid Ferriter, my mentor Susannah Riordan, Clara Cullen, Mary Daly, Michael Laffan, Michael Kennedy, Lindsey Earner-Byrne, Liam Collins, Kieran Allen, all at The Collins Press, Aonghus Meaney, Eunan OHalpin, Paula Murphy, Ivar McGrath, Bryan Fanning and Robin Okey; the talented Jon Everitt, Eileen Lemass, Liam Delahunt, Ann de Valera, amon de Valera, Maureen Haughey, Fionnbharr and Risn Riordn and Angela Rolfe; na MacNamara, Greta Evans, Ros Evans and all my family, especially my grandparents Nora MacNamara and John and Eileen Evans; Anne OGrady, Dennis OGrady, Ed Carey, Anthony Carey, Peter Tighe, John OConnor, Frank Kelly, Doney Carey and Mire Nic an Bhaird, Liz Dawson, Adam Kelly, Sarah Campbell, Fintan Hoey, Aoifie Whelan, Ashling Smith and Paul Hand.

Lastly, thank you to my colleagues and friends in the Department of History and Archives, UCD, and the Humanities Institute of Ireland, particularly Marc Caball, Valerie Norton and my office-mates down the years.

Introduction

The Use and Abuse of the Lemass Legend

N ot another biography of Lemass! Many of the people who have subsequently provided me with help in researching this book initially uttered these words. Their reaction is understandable. Sen Lemass (18991971) has been the subject of no fewer than five published full biographical studies. The publication of this, the sixth, coincides with the fortieth anniversary of his death.

The very fact that this book has been commissioned illustrates the lasting allure of Lemass. Unlike the majority of his political predecessors, peers and successors,the architect of modern Ireland enjoys an unsoiled status in the popular imagination. For a long time Irish historians were preoccupied with the debate on revisionism, a term describing the subjection of national myths to critical scrutiny. Lemass, though, has consistently escaped the revisionists noose. How?

Firstly, Lemass is acknowledged as an extraordinary historical figure. He held key ministerial appointments in every one of amon de Valeras Fianna Fil administrations from 1932 onwards, went on to become Tnaiste and, between 1959 and 1966, Taoiseach. He orchestrated two critical economic transitions in twentieth-century Irish history: the construction, and dismantling, of protectionism. A moderniser who, for his time, was exceptionally receptive to change, Lemasss workaholic commitment is striking. His achievements have been extolled in the ample literature that has grown up around him. This Lemassiography is at times cloying, but his qualities shine through in any work dedicated to him, and this book is no exception.

It would be trite, however, to ignore a major factor in Lemasss enduring popularity: his place in the politics of memory or, to put it plainly, the use and abuse of Lemasss name by Irelands elites. In recent history, successive taoisigh have realised the political capital that comes with paying Lemass lip service. Charles Haughey used to impress visitors to his lavish Kinsealy mansion with a prominently displayed oil painting of his father-in-law, which now hangs at the top of the stairs in Leinster House. The portrait of Lemass in the Taoiseachs office is said to survive all changes of government.

During the belle poque of the Celtic Tiger boom, a period overseen by Ahern and Cowen, Fianna Fil, the political party Lemass helped to found, projected itself as the spearhead of national progress. This modern Ireland, much like a newly emergent state, needed a creation myth. amon de Valera, the post-independence colossus of party and nation, was increasingly seen as peculiar and twee, de Valeras Ireland grim and anti-materialistic. At the same time revelations about the corruption of the modern Boss, Charlie Haughey, the bon viveur antithesis to the frugality preached by de Valera, were uncomfortably close to home. Lemass, however, fitted the bill. In the popular imagination he came to be contrasted with his close political ally, de Valera, and his son-in-law, Haughey. Lemass was invoked as the embodiment of the march of progress, a visionary free trader who kick-started progressive, cosmopolitan, secular, neoliberal Ireland.

When interviewed for this book Tony OReilly, Irelands first billionaire and arguably the greatest success story of Irelands economic miracle, said of Lemass, his personal hero:He had what every great politician needs he was an extraordinarily good poker player! OReillys reflection is an astute one. Like many political leaders of the twentieth century, most notably former US president Richard Nixon, Lemass was an avid poker player. The story of Lemasss life is enduringly compelling because it combined all the elements of the game he loved: intelligence, skill and courage on the one hand; cunning, ruthlessness, luck and deceit on the other. The former aspects of Lemasss game are familiar, but the latter much less so.

To the historian, the darker arts deployed in the game should naturally demand attention. But when it comes to Lemass an entire generation of Irelands historians have neglected them in favour of a tasty dichotomy. De Valera, we are told, stood for an Ireland pious, disciplined and folksy,a real-life version of