HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION

Table of Contents

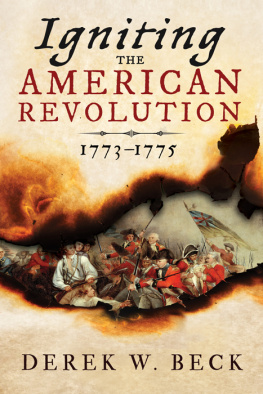

T HE primary cause of discontent among the American colonies, which led to the Declaration of Independence in 1776, was the proclamation by the King of England after the evacuation of America by the French in 1763, forbidding the colonists to extend their settlements west of the Alleghenies.

This proclamation instantly roused the ire of the men of the New World, for the war waged for so many years in the wilderness against the French and the Indians had taught the settlers the incomparable value of their vast Hinterland, and having won at so great cost and by such effort a footing on the coast, they were by no means willing to be dictated to in the matter of expansion. Like stalwart sons of a mighty race, grown to manhood in heroic struggle with the forces of nature, brought to self-consciousness by the conflict they had endured, these men of the New World felt within themselves the power, and therefore believed in their right, to conquer the great and almost unexplored wilderness lying beyond them. From the moment they were made to feel a restriction to their liberty in this direction, there was nothing wanting but a pretext for breaking with the mother country. Nor had they long to wait. One petty act of tyranny after another showed the determination of the English King still to treat as a child the son now grown to manhood. At length the time was ripe and the outbreak came.

Righteous indignation and personal prowess, however, are of themselves unable to win battles or to insure victory. To be effective they must rest upon a material basis, and in the contest of the colonies with England this material basis was conspicuously wanting.

Sparingly provided with munitions of war, possessing no central government, and lacking unity among themselves, the colonies seemed at the first to be leading a forlorn hope. The feeling of resentment roused by the arbitrary interference of England was indeed great, yet the jealousy that existed between the colonies themselves was, if possible, greater still.

Nor was this surprising. Up to the time of forming the determination to break with England there had been no common interest to unite them. Neither habits of life nor uniformity of opinion bound them together; on the contrary, the causes which had brought them into being were just so many forces tending to keep them widely apart. It was this spirit of jealous fear that made of the Continental Congress a body so conspicuously devoid of dignity and incapable of commanding respect either at home or abroad. Composed of delegates representing the colonies, this improvised body found itself, when assembled in Philadelphia, practically without power. It could advise and suggest, but it had no authority to tax the people or even to levy troops.

The presence of members representing different party factions was a fertile source of discord. More than once the whole cause was brought to the brink of ruin through the injudicious actions of this incompetent body. Once it was put to flight by a handful of drunken soldiers and during the entire course of its existence it remained a living demonstration of the fact that where there is no authority, no respect can be commanded, no law enforced.

In this state of affairs help from outside was imperatively needed and eagerly sought. The question that presented itself was, to whom could the Americans turn in their dilemma. Naturally to no second-rate European power, for in combating England, England so lately victorious over all her enemies, powerful support was necessary; and for powerful support to whom could she turn but to France? (Geo. Bancroft, Vol. IV, p. 360.) It is not therefore surprising that we find her looking in this direction. Nor was France herself indifferent to the situation for she was still smarting under the humiliating treaty of 1763. The blood of every true-born Frenchman boiled with indignation when he realized the position to which his proud nation had been brought through the frivolity and egotism of Louis XV. From her place among the nations France had been cast down. She had fallen, not because her own courage or strength had failed her, but because she had been foully betrayed by those who placed the satisfaction of their immense egotism before their countrys honor; she was burning with desire to vindicate herself before the nations of the earth, and to reconquer her place among them. No wonder, then, that she hailed with joy the first symptoms shown by the Americans of resistance to British rule.

On the part of the colonists, however, there was no feeling of real sympathy uniting them with the French. English still at heart, though for the moment fighting against England, the descendants of the Puritans looked with a half disdain upon what they considered the light and frivolous French. More than this, the war terminated by the treaty of 1763 had left many bitter memories:Indian massacres, and midnight atrocities, all laid at the door of Englands historic foe. Moreover, the disinterestedness of her offers of help seemed to the colonists at the beginning to be open to question. Had France for a moment shown signs of a desire to regain her footing upon the western continent, there was not an American but would have scorned her proffered services. Upon this point, indeed, they were onetheir Hinterland. For this they would fight, and in regard to this they would make no compromises.

Perhaps even better than they themselves, France understood the instinctive attitude of the Americans towards their own continent, and her first care was to assure the colonists that in case she should decide to come to their assistance it would be with no intention of laying claim to any part of the New World. (See Recommendations to Bonvouloir, by the Comte de VergennesCanada, he says, is with them le point jaloux; they must be made to understand that we do not think of it in the least.)

But however great her interest in the struggle, however enthusiastic her admiration of the heroic part played by the colonists, she was yet far from desiring to enter prematurely into the contest by openly espousing their cause at the moment. As a people, she might give them her moral support, but as a body politic she was forced to act with extreme caution, for not only was the treasury exhausted, the army and navy demoralized, but above all the irresolute character of the young Monarch, his settled aversion to war, his abhorrence of insurrection, were almost insurmountable obstacles which had to be overcome before the French Government could attempt to send aid to the insurgent colonies.

The interests of France were, however, too deeply involved to permit the ministry to look on as idle spectators, and early in 1775 Bonvouloir had been sent to Philadelphia with secret instructions to sound the attitude of Congress in regard to France, but bearing positive orders to compromise the Government in no wise by rousing in the colonies hope of assistance.

As soon, however, as it became known that a kindly interest was felt for them by France, the secret committee of Congress began to investigate how far this interest could be relied upon for the benefit of their cause.