This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1956 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

TECUMSEHVision of Glory

By

Glenn Tucker

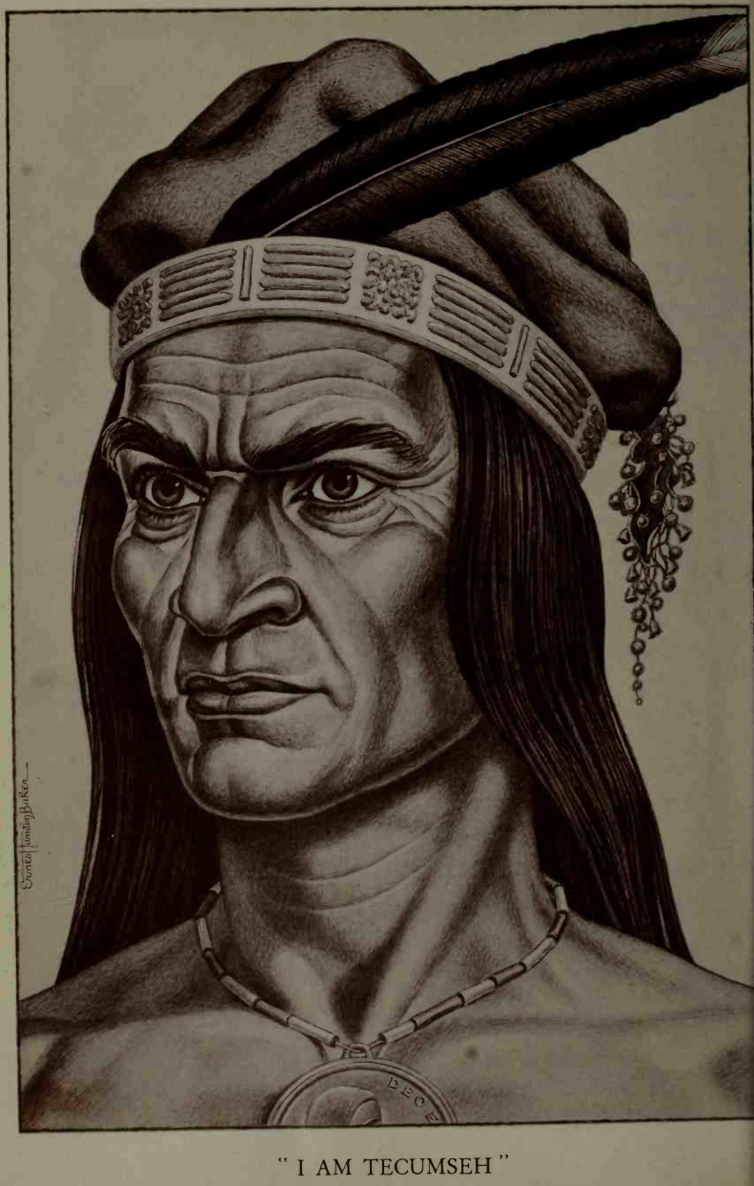

The Tecumseh Portrait

TECUMSEH would never allow a white man to paint his portrait, and no Indian undertook it. A young French trader, Pierre Le Dru, made a furtive pencil sketch of him at Vincennes in 1810.

Benson J. Lossing, the artist-historian, used this and another sketch which he saw in Montreal in 1858 and drew what has remained the standard portrait of Tecumseh. The Montreal sketch did not pretend to be a true likeness but showed the apparel and the medal, or gorget, Tecumseh was wearing. Lossings composite depicts a man of insipid character. It suggests nothing of Tecumsehs ardor and warmth, nor the drive that enabled him to lead a great cause.

The picture on the opposite page is by Ernest Hamlin Baker, one of the countrys best-known artists, whose portraits have appeared regularly on the front cover of Time over the last seventeen years and who developed the portrait style Time employs.

Ernest Baker became deeply interested in analyzing the character and traits of Tecumseh. He read the manuscript of this book, the comments by the chiefs enemies and friends and the descriptions given of him by the pioneers who knew him. He studied Shawnee types, among them George Catlins Indian portraits, including the one made from life by Catlin of Tecumsehs brother the Prophet. He formed his own conclusions about Tecumsehs appearance and dominant characteristics.

Using the Le Dru-Lossing etching as a foundation, he drew a portrait that brings out the lofty pride, the personal magnetism and the commanding power of this ruler of many tribes. Here is a ruthless fighter, but here also is a compassionate man who rises above the unnecessary cruelties of a heartless racial war. The portrait, perhaps the truest likeness of Tecumseh ever made, shows the handling of a noble subject by one of todays outstanding artists.

1Glimpse of Empire

1. A RED CHIEF AGAIN RULES THE PLAINS

TECUMSEH headed south in late September 1812, after the first frost had appeared. The pawpaws and chestnuts were ripe, the bison herds were grazing toward the Ohio, and great flocks of wild ducks moved in ordered array across the sky. The blue haze of autumn was softening the plains. Accompanied by thirty warriors mounted on the best ponies procurable in the Northwest, he crossed the River Rouge from Detroit and struck into the deep woods.

Less than two months before, he and the British commander, Major General Isaac Brock, had executed the plan, largely of Tecumsehs creation, that had led to the astounding capture of Detroit.

The capitulation had included the entire American army commanded by Brigadier General William Hull, a force of 2,500 regulars and Ohio and Michigan militiamen, with thirty-three cannon, abundant ammunition and supplies. Now, as the Michigan sumacs crimsoned and the wind from Lake St. Clair carried the bracing crispness of the Canadian fall, he was starting again on the long journey to enlist the southern tribes in the war for Indian independence.

Chief of the Shawnee, builder of the free Indian confederacy, Tecumseh was leader de facto of the nations that from time immemorial had kindled their council fires on the prairies and in the forests of the great Northwest.

Frontier warfare, with its silken sashes and wampum belts, its epaulets and egret plumes, permitted much pageantry and feathers and, with its buffalo-tail trappings and vermilion paint, much that was garish and hideous. Tecumseh, in contrast, wore unadorned buckskin.

Through the belt that gathered his hunting jacket at the waist were thrust his tomahawk and silver-hilted hunting knife. He was a commanding figure, straight, slim and muscular. The dream of a great mission burned in his hazel eyes. Just as the warriors were attracted to the warmth of the campfire in winter, so they were drawn to the inner blaze that was Tecumseh, now that they were joined in bitter warfare with the hated Long Knives.

His voice was firm and confident and richly resonant with its sonorous Algonquian tones. Now at the age of forty-four, he had acquired a poise and self-assurance, a sort of arrogance, that made him a dominant figure in any gathering of either red men or white.

At this moment, three months after the declaration of war by the United States against Great Britain, Tecumseh was at the summit of his spectacular career. No other Indian had wielded such power. Great portions of North America above the Rio Grande had responded at different times to the commands of a red leader, from Hiawatha to King Philip and on to Pontiac. But the domain of none of them compared in population, in strategic importance, in the fertility of the soil or in extensiveness to the prairie empire dominated in 1812 by the ardent personality and militant patriotism of this Shawnee chief.

The tribes that had sprung to arms at his signal had wiped out Fort Dearborn, on the Chicago River at Lake Michigan, a major trading post of the western lakes. Isolated from Tecumsehs restraint, they had butchered civilians and tomahawked a large portion of the garrison of American regulars. Michilimackinac, controlling the passage to Lakes Michigan and Superior and the key to one of the water routes to the Mississippi, had fallen ingloriously to a minor Indian and British force. Prairie du Chien, commanding the confluence of the Ouisconsin River with the Mississippi, was in British and Indian hands. Fort Harrison at Terre Haute and Fort Wayne at the headwaters of the Maumee River were subjected to harassment or attack. Vincennes and St. Louis were threatened.

Wandering bands, unleashed to vengeful excesses, had carried the war to the northern Kentucky border by their massacre of the entire population of Pigeon Roost, Indiana. An exodus of settlers from Ohio and southern Indiana to Kentucky and Pennsylvania was beginning. Over the far-flung territory north and west of the Wabash and Maumee rivers, comprising the heart of the North American continent, American rule had disappeared.