Openwork disc brooch of gilt bronze (D 3.9 cm/1 in.), from Pitney churchyard, Somerset, England. It features an animal-and-snake combat motif in the English version of the Urnes style (see ).

About the Author

James Graham-Campbell was educated at Cambridge and studied as a postgraduate in London and in Scandinavia at the Universities of Bergen and Oslo. He is emeritus professor of medieval archaeology at University College London and is a Fellow of the British Academy. His lifetimes study of the Vikings and their art has focused particularly on silver hoards and the pagan Norse burials of Scotland. His many publications on the subject include The Viking World, The Vikings (with Dafydd Kidd), Vikings in Scotland:An Archaeological Survey (with Colleen Batey), The Cultural Atlas of the Viking World (as editor) and, most recently, The Cuerdale Hoard and Related Viking-Age Silver and Gold from Britain and Ireland in the British Museum.

For Otelo Miranda Fabio

Acknowledgments

My greatest debt is to David M. Wilson whose teaching first aroused my interest in Viking art and whose continuing guidance has long sustained my involvement in Viking studies. His friendship has extended to reading a draft of this book, which is all the better for this kindness, although this in no way commits him to any of the opinions expressed here. I also wish to acknowledge my gratitude to Signe Horn Fuglesang for numerous discussions on the subject of Viking art, arising out of her own research and her many publications on the subject to which frequent reference is made. My old friend and colleague, Else Roesdahl, is to be warmly thanked for her assistance with the provision of illustrations, so ably gathered together for me by Maria Ranauro. It is, finally, a pleasure to record my thanks for the friendly and efficient manner in which my editor, Alice Reid, eased this book into existence, as also to the rest of the team at T&H involved in its design and production. For help with revisions to the new edition, I thank Jane Kershaw, as also Judith Jesch and Else Roesdahl.

Contents

The last decade of archaeological discovery, through both excavation and metal-detecting, has seen numerous important discoveries made in many parts of the Viking world that contribute to our better understanding of the period when combined with the re-evaluation of existing material in museum collections.

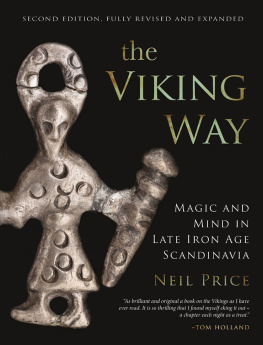

In recent years much thought has been devoted to the character of belief and ritual in the Viking Age, in particular by Neil Price, whose acclaimed doctoral dissertation, The Viking Way, originally published in 2002, has been fully revised and expanded, with the subtitle Magic and Mind in Late Iron Age Scandinavia (2019). To a considerable extent such studies are informed by Viking art, with a new emphasis being placed on it as narrative art, whereas the traditional approach has been to view the Scandinavian animal styles as mostly decorative, if with symbolic content.

An important contribution in this respect is a paper by Peter Pentz on Viking Art, Snorri Sturluson and Some Recent Metal Detector Finds (2018). His conclusion that we now may claim the opposite because Viking artists almost always intended their work to represent something specific perhaps overstates the case, but it is certainly true that our ability to recognise Viking art as narrative art has improved substantially, largely as a result of metal-detecting activity. Such recent finds include the first three-dimensional depiction of an armed woman known from the Viking Age, in the form of a silver pendant, worn perhaps for luck in battle.[] In preparing this new edition of Viking Art the opportunity has been taken to expand the original chapter on Content, with the introduction of some further illustrations enabling the addition of several such new discoveries.

Gilt-silver pendant, with decorative details picked out in black niello inlay (H 3.4 cm/1 in.), in the form of a long-haired female warrior armed with sword and shield a valkyrie? Found by a metal-detectorist in 2012 near Hrby, in western Fyn, Denmark. Valkyries, their name meaning choosers of the slain, were believed to convey dead warriors from the battlefield to Valholl (or Valhalla), the Hall of the Slain presided over by the god Odin (see ).

No general survey of Viking art has appeared during the last decade and art was not featured as such in the most recent international exhibition on the Vikings, seen in Copenhagen, London and Berlin, although its catalogue Vikings: Life and Legend (2014) contains information on a variety of recent finds, including ornamental metalwork. On the other hand, the annotated online bibliography, Viking Art, prepared by James Graham-Campbell and Jane Kershaw (Oxford Bibliographies in Art History, 2016) provides additional information in the form of commentaries on a wide range of publications covering all aspects of the subject (see the updated list of ).

Minor alterations and corrections have been made throughout the book, to both the original text and captions, incorporating new and updated information, both archaeological and chronological.

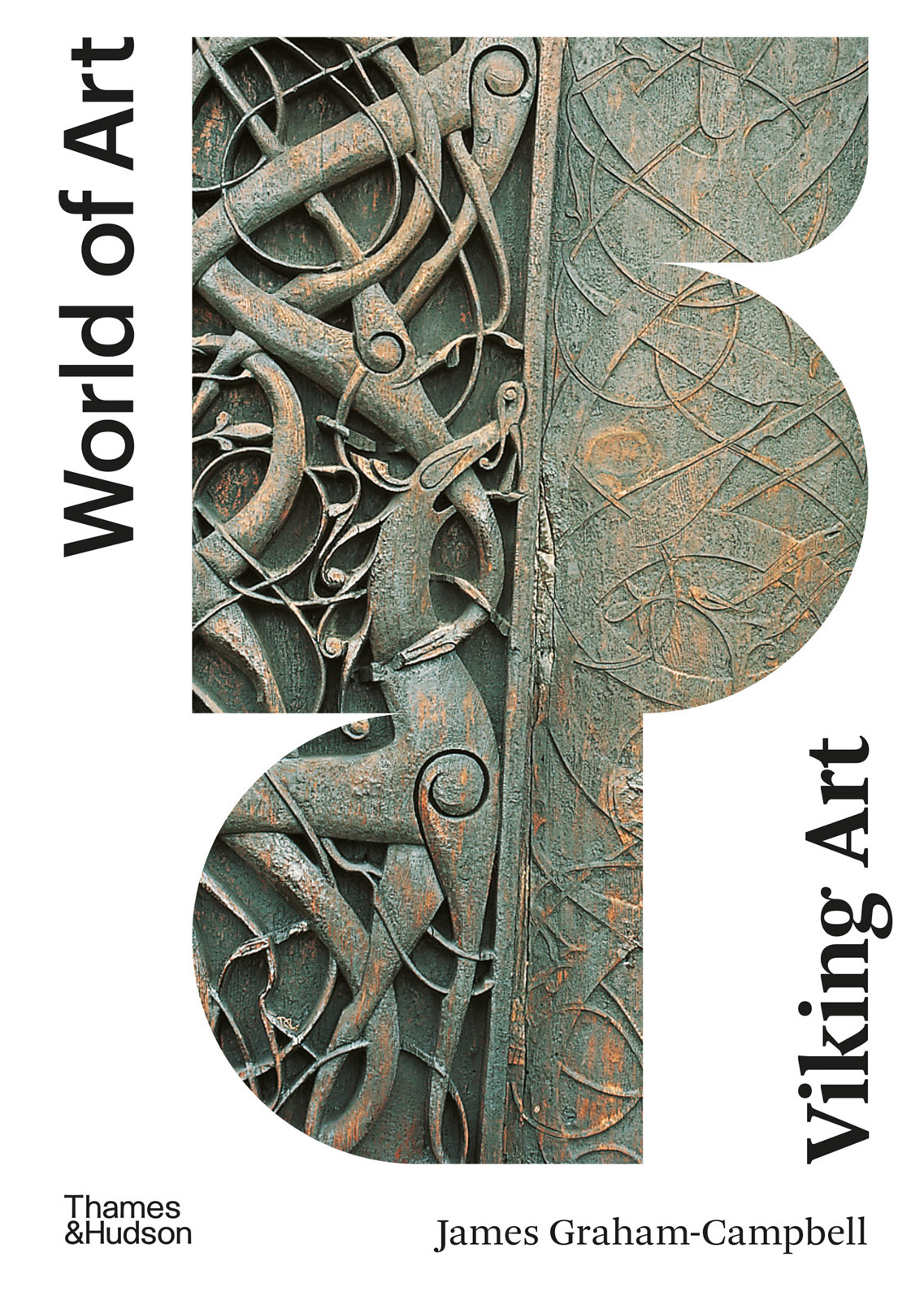

This book sets out to provide a general survey of the visual arts of Scandinavia during the Viking Age, covering also typical Viking Age works produced in the Scandinavian settlements overseas, from Iceland to Russia (including Britain and Ireland). Modern historians mark the beginning of this period by the commencement of regular expeditions out of Scandinavia during the late eighth century AD undertaken by people we know as the Vikings rather than defining it by any particular political or social development in the lands of Denmark, Norway and Sweden. These foreign excursions were carried out by sea and river for the purposes of raiding and/or trading, but they also inevitably resulted in new foreign influences reaching Scandinavia, some of which are evident in the development of Viking art. The ultimate external influence on Scandinavia during the Viking Age was the introduction of Christianity, such that the full establishment of the Church can reasonably be taken as marking the end of this period, in the late eleventh century.

Viking Art covers these 300 years. Its title is, however, something of a misnomer. In the first place, the word art in this context is not restricted to fine art (though there are pieces created in connection with religious beliefs, both pagan and Christian, that do fall into this category): in fact the primary purpose in creating the majority of the works described here was that they should be used. Most of the material under consideration that is to say ornamental metalwork was both functional and decorative, however finely executed.[]

Secondly, viking is the modern English form of the Old Scandinavian word vkingr, normally translated as sea warrior, with

Next page

![Haywood - Viking: The Norse Warrior’s [Unofficial] Manual](/uploads/posts/book/98981/thumbs/haywood-viking-the-norse-warrior-s.jpg)