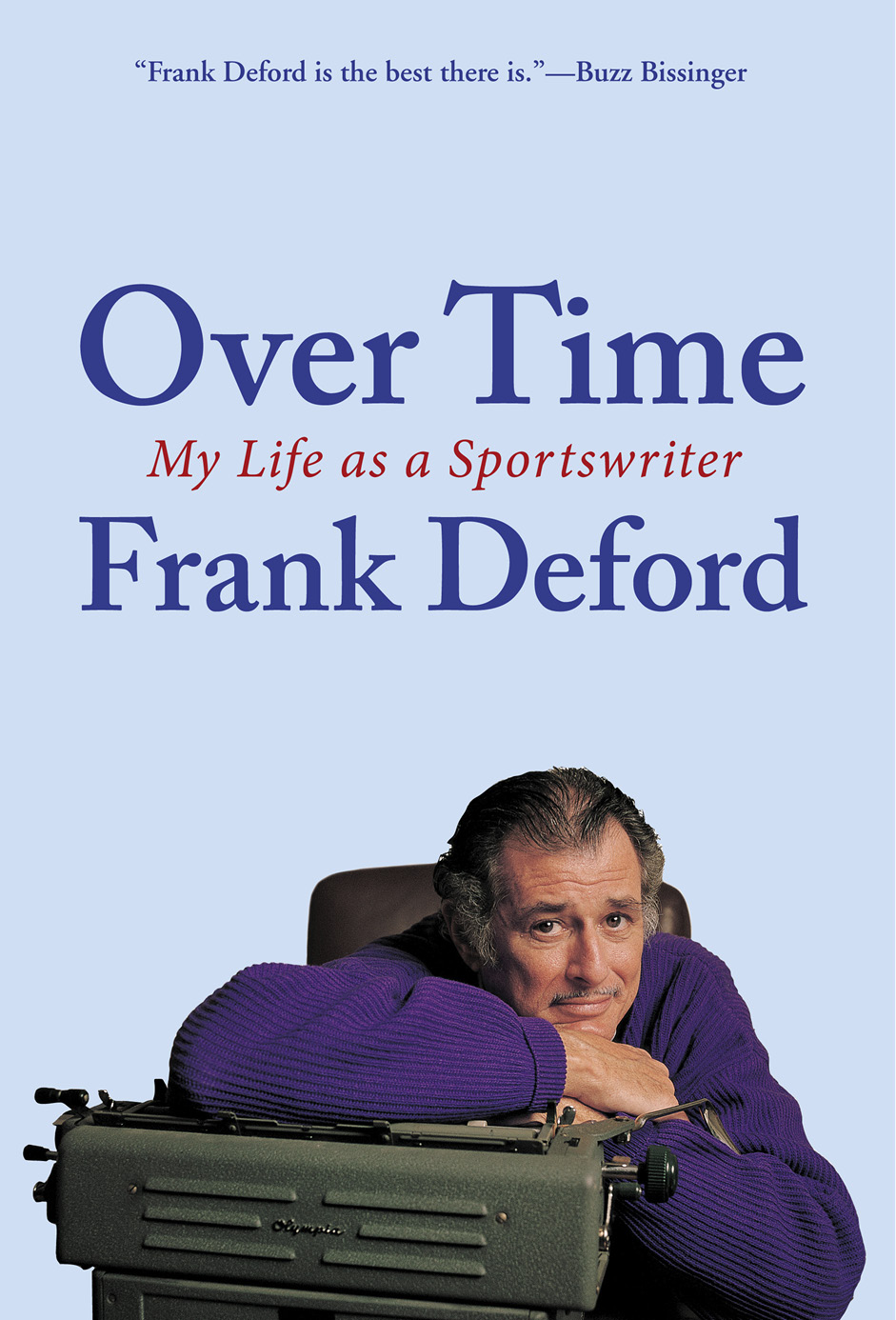

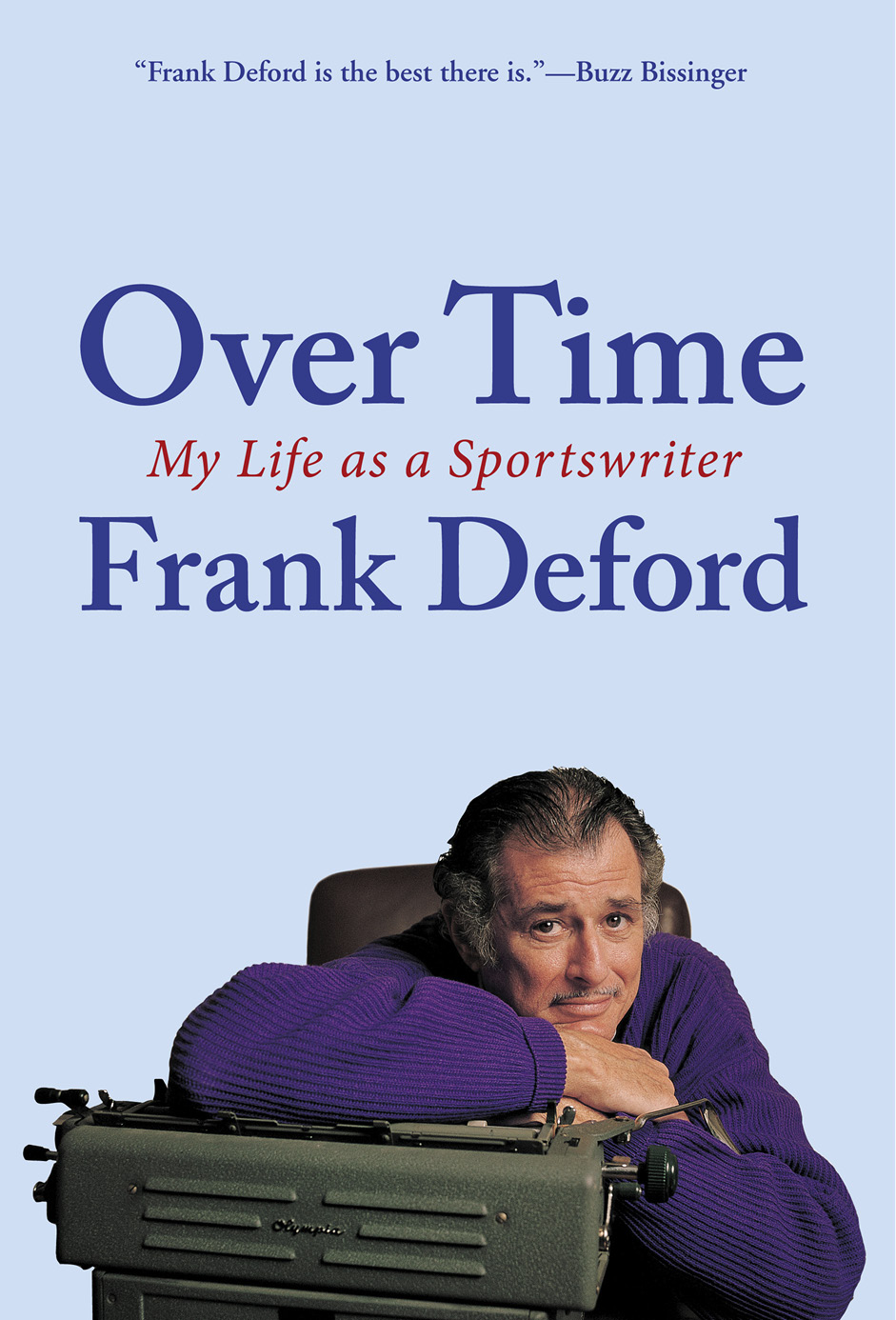

OVER TIME

Also by Frank Deford

FICTION

Cut n Run

The Owner

Everybodys All-American

The Spy in the Deuce Court

Casey on the Loose

Love and Infamy

The Other Adonis

An American Summer

The Entitled

Bliss, Remembered

NONFICTION

Five Strides on the Banked Track

There She Is

Big Bill Tilden

Alex: The Life of a Child

The Worlds Tallest Midget

The Best of Frank Deford

The Old Ball Game

OVER TIME

M Y L IFE A S A S PORTSWRITER

FRANK DEFORD

As Told to Frank Deford

Atlantic Monthly Press

New York

Copyright 2012 by Frank Deford

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove/Atlantic, Inc., 841 Broadway, New York, NY 10003 or .

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN-13: 978-0-8021-9456-5

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove/Atlantic, Inc.

841 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

Distributed by Publishers Group West

www.groveatlantic.com

contents

13. In Which I Finally Discover the Difference

Between Winning and Losing

27. The Most Amazing Feat in Sport in

the Twentieth Century

38. The Sweetest Thing I Ever Saw an Athlete Do

for a Member of the Fourth Estate

For

Jerry Downs

and

Nemo Robinson

A NOT VERY BRIGHT BOY

I was still enough of a child to think that anger could best be expressed with perversity.

An American Summer, 2002

After my junior year at Princeton, it another desultory academic lay-by, I decided I might as well go into the army and get it over with. In those days of the draft a healthy enough American boy had to do that for at least six months. I chose the least. This was during that peaceful lull separating Korea from Vietnam, though, so I was but a tweener, passing through when nothing much was going on in a martial way.

My military highlight, such as it was, came when the sergeant said to me: DeFord, you wanna be the guide-on? I had no idea what that was, but it sounded OK, so I said, yes, Id like that. Good answer. The guide-on, I discovered, is the guy who carries the flag that the other soldiers follow after. Guide-on would not have been a good job, say, on Picketts Charge in 1863, but at Fort Dix in 1961, when no one was firing live rounds, it was an excellent vocation.

It wasnt even that I had earned the job of guide-on. It was just that I was the tallest man in my company, so for most of my military tenure I played retirement ceremonies, just holding a flag and standing tall, which I can do perfectly well. I was no better a soldier than I was a student. In fact, in some respects Ive never grown up. Primarily, I dont think Ive ever learned to do anything new since I was about nine years old, when I first discovered that I had some facility for writing and speaking. Well, I did learn about sex later on. But thats instinctive, so I dont think it can necessarily be counted as another arrow in my quiver.

Anyway, as a returning serviceman, I put mufti back on and reconnoitered Princeton for one last year, there to officially conclude my education and contemplate my future. The main thing was, I wanted to go to New York, which is where I knew writers went to write and live life large. Prefiguring LeBron James, you might say, I decided to take my talents to midtown. But while Gotham beckoned me, I was not the sort of virtuous artiste who was willing to live in a garret and wait tables while I wrote the Great American Something. At a minimum, I needed a comfortable roof over my head and some walking-around money.

Fortuitously, one day I saw a notice that Time Incorporated would be interviewing on campus. The companys celebrated, respectable magazines Time, Life, and Fortune were not, I thought, the right sort of showcase for my presumed ability, but Id been a reader of Sports Illustrated and very much admired the writing in the magazine. Whereas it had a lot of yummy stuff about yachts and show dogs and what tweeds to wear when tailgating at the Yale Bowl, there was, in counterpoint, some awfully good writing in it. I also figured that, as a starter course, a magazine would be a better fit for me than would a newspaper, as I imagined that the larger canvas was better suited for my more expansive, embroidered style.

I bundled up my choice clippings and went to see the interviewer. He was a Mr. Titmana name Dickens had somehow missed. At first Titman told me that he really wasnt interviewing people who wrote, that he was just after business typesinformation I found a little disconcerting, coming from a publishing companys talent scoutbut as I was about to scoop up my clips and depart, something crossed his mind. Titman was a Princeton man himself, and he recognized me from articles Id written for the alumni magazine, and so, as a loyal Tiger, he very nicely said hed go the extra mile and look into getting me an interview. So, there: thanks to Titman, now I was an official cog in the celebrated Old-Boy Network. My vaunted Princeton educationuh, affiliationhad already paid off.

Of course, understand: in 1962 it was hard for someone like me, an Ivy League Wasp, not to move to the head of the line, for certain rather prominent subgroupsnotably the female gender and all racial and ethnic minoritieswere not taken seriously at that time. Diversity was not yet a concept. In many distinguished places of business in New York then, what passed as diversity meant making sure not to hire too many Andover graduates at the expense of Exeter. Plus, I was born at the right time; I was that rare specimen, a Depression Baby. Better yet, I had been conceived early in 1938, at a time when there was a recession in the middle of the Depression . Except for my dear parents, almost nobody in America with any sense was having babies around the time I was born. So when I got out of college, there were only a handful of us coming onto the job market in the United States of America. It was actuarial affirmative action. While all those subsequent oodles of War Babies and Baby Boomers would have to go all-out Darwinian all their lives, we Depression Babies got a pass.

Because of this demographic serendipity, it was a sellers market extraordinaire, and I could approach job interviews with aplomb. So it was, on my appointed day, that I took the train into New York and boldly presented myself at the Time Incorporated personnel office. There, I was handed two things. First, a list of the editors I was scheduled to see. Second, a folder with my name on it: Frank DeFord. I was advised to hand the folder to each big-shot Timeink editor that I met. Now, nobody told me not to look inside the folder, but even if anyone had, I wouldve had to be inhumanly incurious not to. So, first chance I got, I sneaked a peek. Samples of my writing were in there, but on top was sort of an assessment of who this particular Depression Baby candidate might be, and here were the very first words typed there to sum me up:

Next page