CONTENTS

About the Book

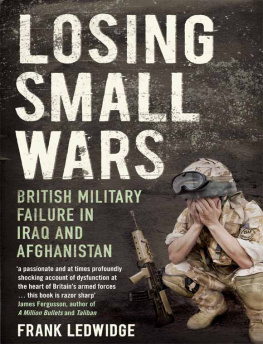

On 15 September 2003 Baha Mousa, a hotel receptionist, was killed by British Army troops in Iraq. He had been arrested the previous day in Basra and was taken to a military base for questioning. For forty-eight hours he and nine other innocent civilians had their heads encased in sandbags and their wrists bound by plastic handcuffs and had been kicked and punched with sustained cruelty.

A succession of guards and casual army visitors took pleasure in beating the Iraqis, humiliating them, forcing them into stress positions in temperatures up to 50 degrees Centigrade, and watching them suffer in the dirty concrete building where they were held. Other soldiers, officers, medics, the padre, did not take part in the violence but they saw what was happening and did nothing to stop it. Some knew it was wrong. Some werent sure. Some were too scared to intervene. But none said anything or enough until it was far too late and Baha Mousa had been beaten to death.

This book tells the inside story of these crimes and their aftermath. It examines the institutional brutality, the bureaucratic apathy, the flawed military police inquiry and the farcical court martial that attempted to hold people criminally responsible. Even though a full public inquiry reported its findings into the crimes in September 2011, its mandate restricted what it could say. The full story, told with the power of a true-crime expose or court-room drama, shows how this was not simply about a few bad men or rotten apples. It shines a light on all those involved in the crime and its investigation, from the lowest squaddie to the elite of the army and politicians in Cabinet. What it reveals is devastating.

About the Author

Andrew Williams is a law professor at the University of Warwick and Director of the Centre for Human Rights in Practice.

A VERY BRITISH KILLING

The Death of Baha Mousa

A. T. WILLIAMS

Preface

VERY LITTLE IS remembered about the Iraq war now. It has been reduced to not much more than piecemeal images: the night sky over Baghdad, lit up by flares and explosive bursts; the statue of Saddam Hussein being pulled over by ropes attached to a tank; wailing women and men splattered with blood and shell dust after a car bomb has been detonated in a busy street market; patrolling soldiers dressed in desert combat trousers and flak jackets, carrying automatic rifles at the ready as cars and pedestrians pass by in a mirage of normality; a tanned Tony Blair expressing no regrets before a panel of inquirers and a brittle voice shouting shame behind him; a white tent in an Oxfordshire field, covering the corpse of a scientist who had spoken freely with a journalist about Saddams non-existent weapons of mass destruction; a man dressed in a black suit walking through a quaint English village, a hearse crawling behind him, a crowd hushed then clapping, throwing flowers on to the car; a bearded erstwhile president of Iraq having his gums and teeth inspected roughly by a US medic; a photograph of an Iraqi man standing with his wife and two young boys, posing for a family portrait to be hung on a whitewashed wall in a small anonymous house in Basra.

This book is about the last of these. On 15 September 2003 the man in the photograph, Baha Mousa, a hotel receptionist, was killed by British Army troops in Iraq. He had been arrested the previous day and taken to a military base for questioning. For two days he and nine other civilians had their heads encased in sandbags and their wrists bound by plastic handcuffs and were kicked and punched with sustained cruelty. A succession of guards and casual army visitors took pleasure in beating the Iraqis, humiliating them and watching them suffer in the dirty concrete building where they were held. Other soldiers, officers included , did not take part but they saw what was happening and did little if anything to stop it. Some knew it was wrong. Some werent sure. Some were too scared to intervene. But few said a word until it was far too late.

Superficially, this book is an investigation into the crimes that were committed in relation to Baha Mousa and his fellow detainees. It examines the military police inquiry which followed Bahas death and the ultimately farcical attempt to hold people criminally responsible. But theres also a deeper story told here, which the bare facts obscure. Over the past fifty years British forces have engaged in no fewer than seventeen wars around the world. In each one there have been incidents which mirror those suffered by Baha Mousa: illegal killings, torture, cruel treatment committed by British forces. And in every conflict the institutional response has been ambivalent if not duplicitous. The public condemnation of those bad apples occasionally exposed as culpable has never quite hidden a culture of contempt and indifference permeating the army and government hierarchies. Protestations that Britain respects and promotes human rights and the laws of war have been accompanied by civilian and military commanders who do everything they can to look the other way or even bury cases of abuse. Systems of criminal investigation have been established to pursue those responsible, but they are not impartial, independent or effective. Official handwringing and apology have been joined by decisions and tactics preventing proper and full examination of those same crimes and others which are similar. And claims that the rule of law governs official action have been accompanied by deliberate attempts to avoid legal scrutiny. All in all the approach is very British: apologetic but ultimately disdainful of the suffering of people living in distant countries.

The killing of Baha Mousa holds up a mirror to this very British attitude. It reflects a light on all those foot soldiers and staff officers, civil servants, medics and lawyers, priests and politicians involved in the crime and its investigation, from court martial to public inquiry and private litigation. But it also tells us something about who we are and what is done in our name. The images of the Iraq War may warp and fade but the photograph of Baha Mousa and his family should not. It is a reminder of what being British has meant for others.

Part 1

IN IRAQ

IT WAS SHORTLY after dawn and already the heat was suffocating. Outside the army field hospital near Shaibah in south-eastern Iraq, fifteen kilometres south-west of Basra, a white tent had been erected on the sand a few yards apart from the main buildings. It was a police-type marquee, similar to those used to preserve crime scenes, large enough for several men to work in comfortably, if that could be possible with the temperatures already rising well above forty-five degrees centigrade. Inside the tent there was a wooden table and on the table was a mans body.

The body, solid and broad, was rudely dressed in black cotton trousers pulled down from the waist a little way over the thighs. They were sodden and split at the back. The corpse had been kept in a morgue freezer for five days and had been brought to the tent four hours earlier. It had begun to thaw and ooze fluid in the escalating temperatures inside the tent. Signs of putrefaction were becoming evident.

Next to the torso lay other items of clothing; a white vest and a green shirt. They too were ripped as though having been cut off the body and then discarded by its side. The body was tagged, a white plastic identity bracelet on the left wrist, a black tag on the right ankle. A plastic pipe projected out of the mouth. There were large circular white pads attached to the chest and an intravenous tube was still inserted into the vein in the crook of one arm, the signs of frantic but failed attempts at resuscitation.