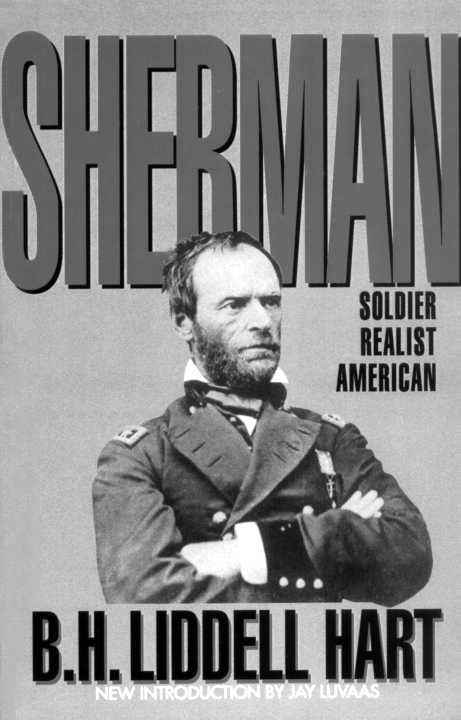

GENERAL WILLIAM T. SHERMAN

By B. H. LIDDELL HART

To MY FATHER-AND FRIEND

INTRODUCTION

Sherman and the "Indirect Approach"

In 1928 Captain B. H. Liddell Hart, an English military journalist, theorist, and reformer already well known for his provocative writings on military tactics, training, and mechanization, was asked by an American publisher to write on one of the great figures of the American Civil War, "preferably Lee.". Two years previously he had published his first book of an historical nature, A Greater than Napoleon -Scipio Africanus, soon after followed by Great Captains Unveiled, a compilation of articles about Jenghiz Khan, Saxe, Gustavus Adolphus, Wallenstein, and Wolfe. Both books reveal a careful reading of the primary sources and an acquired skill in making the past speak to the present on questions of tactics, strategy, and organization.

He chose instead to focus on William Tecumseh Sherman, in his judgment "the most original and versatile" of the Civil War commanders and an ideal vehicle for conveying his own emerging theories of mobile warfare and the strategy of "Indirect Approach." Determined to avoid repetition of the trench deadlock of 1914-18, where massive assaults had resulted only in massive casualties, Liddell Hart had already turned to mechanization as the way to restore mobility to warfare. Now he hoped that Sherman, whose campaigns in 1864 had overcome "a somewhat similar deadlock," might provide clues that could be applied to the present. For his purposes Lee's campaigns were less relevantand Lee himself, however skilled in the operational art, was no innovator.

By 1927 Liddell Hart had begun to realize that a direct approach to the objective along the line of natural expectation usually yielded negative results, and when he began research for the Sherman biography the following year all the ingredients for his "Strategy of Indirect Approach" fell into place the concept of "deep strategic penetration," the importance of simultaneously threatening "alternative objectives," and the "baited gambit," which combined offensive strategy with defensive tactics. Had Liddell Hart already formulated his "Strategy of Indirect Approach," Sherman could have provided convincing examples, but in fact it was the other way around. Only by entering Sherman's thought process could Liddell Hart develop his theory in detail, and in his Memoirs he acknowledged that reading the message traffic in the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies gave access to "the-day-to-day, and even hour-by-hour impressions and decisions" of commanders on both sides. A glance at Sherman's official letters and orders throughout the Atlanta Campaign and during the subsequent march to the sea offers convincing evidence that Sherman had indeed pondered the thoughts and alternatives attributed to him.

In 1929, the same year that Sherman was published in the United States, Liddell Hart produced another book that elevated Sherman's operational techniques into a doctrine adaptable to mechanized war, using examples from the more distant past to substantiate his theories and give them universal validity. In only six of more than 280 campaigns, he asserted, had decisive results followed a strategy of direct approach.

History shows that rather than resign himself to a direct approach, a Great Captain will take even the most hazardous indirect approach-if necessary, over mountains, deserts, or swamps, with only a fraction of his force, even cutting himself loose from his communications. Facing, in fact, every unfavourable condition rather than accept the risk of stalemate.'

The Decisive Wars of History was followed a decade later by a second edition entitled The Strategy of Indirect Approach, which included the most recent campaigns in World War II. Subsequent editions dealt with the "Indirect Approach" as it had been applied in the Arab-Israeli War of 1948, and had Liddell Hart been alive at the time of the recent Gulf War he most assuredly would have compared the so-called "Hail Mary" maneuver in Desert Storm to Sherman's plan to pry the Confederates out of their mountain fortifications around Dalton in May, 1864-pointing out of course that General Schwarzkopf was reputed to have had a copy of Sherman's Memoirs on his night stand. Certainly he would have made much of the fact that FM 100-5, the current U.S. doctrinal manual supporting AirLand Battle, asserts that "successful tactical maneuver depends on skillful movement along indirect approaches supported by direct and indirect fires," that the ideal campaign plan "embodies an indirect approach that preserves the strength of the force for decisive battles," that "the ideal attack should resemble what Liddell Hart called the `expanding torrent,' " and that

surprise and indirect approach are desirable characteristics of any scheme of maneuver. When a geographically indirect approach is not available, the commander can achieve a similar effect by doing the unexpected - striking earlier, in greater force, with unexpected weapons, or at an unlikely place.2

On this point, Sherman and Liddell Hart would have agreed.

There is evidence that Liddell Hart's Sherman had an immediate if perhaps a somewhat superficial impact on the British army. The principal exercises in 1931, stressing significant reduction in the scale of transport and the weight of the soldier's load, were known as "a Sherman march," and in 1934 the first complete armored force in the British army conducted exercises in making deep thrusts into the "enemy's rear areas." In 1932 a future German War Minister and Commander-inChief conveyed to Liddell Hart that he had been "greatly impressed" by his exposition of Sherman's technique and was applying it in his own training methods. As later events would show, he was not the only German General to accept the idea of deep strategic penetration by armored forces.'

Several months before the Allied landings in Normandy in 1944, Liddell Hart had an opportunity to talk with General George Patton, who claimed

that before the war he had spent a long vacation studying Sherman's campaigns on the ground in Georgia and the Carolinas, with the aid of my book. So I talked of the possibilities of applying "Sherman methods" in modern warfare-moving stripped of impedimenta to quicken the pace, cutting loose from communications if necessary, and swerving past opposition, instead of getting hung up in trying to overcome it by direct attack. It seemed to me that by the development and exploitation of such Sherman methods, on a greater scale, it would be possible to reach the enemy's rear and unhinge his position -as the Germans had ready done in 1940. I think the indirect argument made some impression.... The way that, after the breakthrough, he actually carried out his plans, in superSherman style, is a matter that all the world knows.'