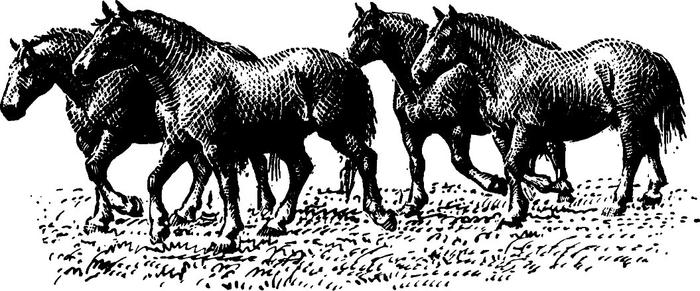

T he purpose of this book is to record the history of the farming associated with the horse in a part of East Anglia. Although he has by no means ceased to be used on the farms of Suffolk, the era when the horse was the pivot of the corn-husbandry of this area has come to an end; and the generation of horsemen or ploughmen who best remember the full horse-regime has gone from the land. Many of the farmers who were brought up on, and practised, the old system of farming for the greater part of their lives have also retired or are near retiring age. The book has been attempted at this particular timeso near to the passing of the horse as the main power on the farmchiefly in order to take down first-hand information from the men who knew the old regime in its most complete form, before the changes of the last fifty years had begun to revolutionise agriculture. The farm, especially in Suffolk, revolved round the horse; and the care and attention which the old type of farmer and his men bestowed on his horses and on their breeding was a recognition of their importance . Goodhorses:goodfarm, was more than a saying: it pointed to the mainspring of a system of husbandrythe four-coursethat had its home in the Eastern Counties.

Much of the material set down here has been collected from farmers and farm-workers whose evidence has been checked and correlated with documents and records of Suffolk farming methods during the past two hundred years. I had no hesitation in seeking agricultural history from the working farmer in Suffolk. As Sir Frank Stenton, manorial farming. When the period studied is nearer the present day, the farmer is naturally able to give much greater assistance still.

During the preparation and writing of this book I found the Suffolk farmer an invaluable help, both in supplementing and expounding the written sources. For the farmer in this county is usually in the direct line of a very long tradition: not only has farming been the whole of his life but it has been the life of his family for the past two hundred years. Often when studying records of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries I came up against little problems that could not be solved by reference to any known book or document: I sought the help of the older generation of farmer and in nearly every instance I got what I was looking for. I discovered that not only did their farming knowledge extend over the period covered by their own working life, but often embraced the experiences of their fathers and grandfathers, reaching back into the first half of the nineteenth century .

Similarly, I did not hesitate to go for help and enlightenment to the old hands who had spent most of their life with the horses on the farm. It would be accurate to say of these horsemen, during the period before the First World War, that horses and farming were the whole of their lives: they had a seven-day-a-week job; they talked, lived, and almost dreamed horses; and when they did go abroad it was either to an agricultural show or to an event that was connected either directly or indirectly with their work. I found the old horsemanwherever I met him in the countyhelpful, highly intelligent within the field of his own experience, and accurate to a degree that many people would find it difficult to credit. But when one reflects that farming was his sole interest, from the time he started as a boy of about twelve years of ageperhaps sixty years beforeand that he had trained his mind to hold all the data he needed in his job, without the aid of books, or at the most with only the barest of written memoranda , it is not surprising that he was able to recount in accurate detail something he was interested in and had perhaps not seen for thirty or forty yearsan early corn-drill, for example; which checked against an old catalogue showed that not one essential fact had escaped his memory.

that was imposed on the countryside by the 1870 Act and he might lack the graces of what passes for a typical twentieth century product. Yet were some of his limitations in this respect to be brought to his notice, he could ask with point: Who is the truly educated man: the one who can grow onions or the man who can only spell em?

The reader will notice that They dont do it like they used to, or Times are not what they were is the undersong of much of the information given by many of the people I have talked to in preparing this book. But times were never what they were: men have never worked as hard, been as strong and as noble and as thick in the thews as they were a generation or two in the past. Distance in time is a powerful enchanter of the eye. Yet in these later days the older men have a greater sanction for repeating the old theme than perhaps ever before. For in their life-time they have seen, not merely the passing of a few generations, but the passing of an era. They are praisers of past time because less than any men before do they understand the age they have survived into. How can they, when so few of their superior and educated contemporaries have an inkling where the present age is tending and what it is all about?