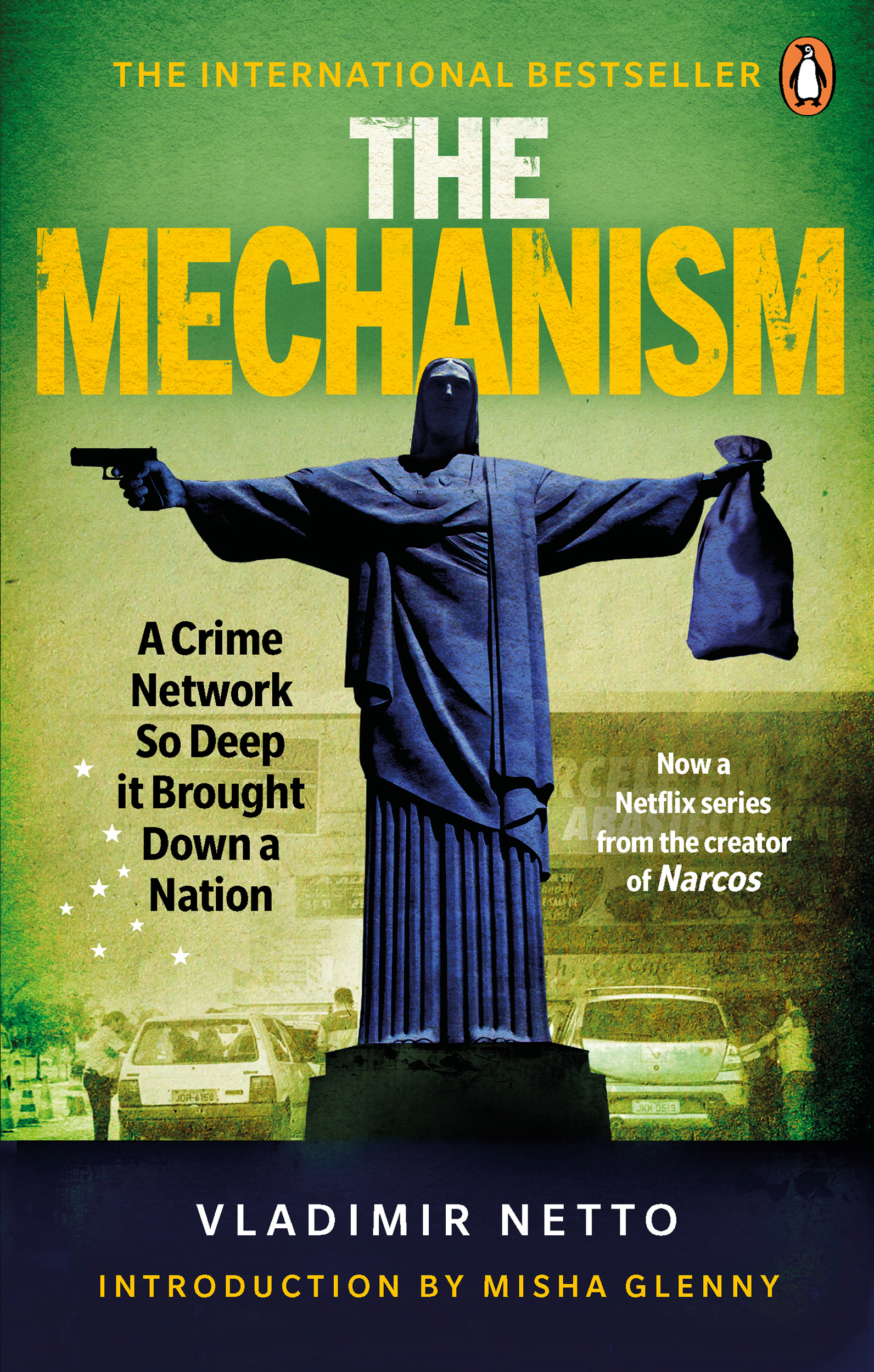

Vladimir Netto

The Mechanism

A Crime Network So Deep it Brought Down a Nation

Contents

About the Author

Vladimir Netto (Author)

Vladimir Netto has been a journalist for twenty-two years. He is a reporter for Globo TV and the vice-president of the Brazilian Investigative Journalism Association. He has received several awards, most of which connected to scoops in big corruption cases. The Mechanism is his first book, and was the bestselling non-fiction book in Brazil in 2016.

Robin Patterson (Translator)

Robin Patterson has translated or co-translated a variety of works by Portuguese, Brazilian and Angolan authors, including Luandino Vieiras Our Musseque, Jos Lus Peixotos In Galveias, Lcio Cardosos Chronicle of the Murdered House (which won the 2017 Best Translated Book Award), and The Collected Stories of Machado de Assis.

The legal status on 1 January 2019 of all individuals connected to this case can be found on .

Key Players and Political Parties

POLITICIANS

Luiz Incio Lula da Silva (Lula), 35th President of Brazil

Dilma Rousseff, 36th President of Brazil

Renan Calheiros, speaker of the Senate

Delcdio do Amaral, Workers Party leader in the Senate

Eduardo Cunha, speaker of the Chamber of Deputies

Joo Vaccari Neto, Workers Party treasurer

Jos Dirceu, former government minister

Fernando Collor de Mello, senator and 32nd President of Brazil

JUDGES AND PROSECUTORS

Teori Zavascki, Justice of the Federal Supreme Court

Sergio Moro, federal judge in the southern city of Curitiba

Rodrigo Janot, prosecutor general of Brazil

Deltan Dallagnol, federal prosecutor leading the Car Wash task force

PETROBRAS EXECUTIVES

Paulo Roberto Costa, director of Supply Division

Nestor Cerver, director of International Division

Renato Duque, director of Services Division

Pedro Barusco, executive in Services Division

BUSINESSMEN AND INTERMEDIARIES

Marcelo Odebrecht, chairman of Odebrecht group

Ricardo Pessoa, chairman of UTC Engenharia

Augusto Mendona, executive at Toyo Setal

Jlio Camargo, consultant

Fernando Baiano Soares, lobbyist

Alberto Youssef, black-market currency trader

Jos Carlos Bumlai, businessman friend of Lulas

POLITICAL PARTIES

PMDB (Partido do Movimento Democrtico Brasileiro): Brazilian Democratic Movement

PP (Partido Progressista): Progressive Party

PSDB (Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira): Brazilian Social Democratic Party

PT (Partido dos Trabalhadores): Workers Party

PTB (Partido Trabalhista Brasileiro): Brazilian Labour Party

SDD (Solidariedade): Solidarity

Introduction

MISHA GLENNY

Brazil matters. Not just to Brazilians but to every inhabitant of this planet. Its by far the biggest country in South America and the number one exporter of iron ore, coffee, orange juice, beef and soya to name just a few commodities. It is currently the ninth largest economy in the world, but by 2050 analysts are confident that it will be the fourth largest after China, India and the US. But the critical reason we need to understand whats happening in Brazil is the Amazon. This rainforest is the lungs of our planet. Brazil has stewardship over 60 per cent; how it chooses to manage the Amazon will have an impact on all of us.

The book you have in your hands is vital to understanding the countrys immediate past, its present and its unpredictable future.

I am writing this introduction in the wake of the inauguration of Brazils new president, Jair Bolsonaro. The new leader makes no secret of his ideology or his political intentions, as his frequent use of misogynist, racist and homophobic language testifies. He eulogises Brazils military dictatorship, which lasted for twenty-one years from 1964. During impeachment proceedings against the left-wing president, Dilma Rousseff, he lavished praise upon a former colonel, Carlos Brilhante Ustra, who headed up the torture unit at the time when Rousseff was a political prisoner.

Following the result of the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump in the US, the rise of Bolsonaro is yet another disturbing example of the polarisation of public discourse since the financial crash of 2008. But his success also confirms how right-wing populists around the world have been able to exploit the anger triggered by economic failure and political stagnation much more effectively than liberals, social democrats and the Left.

The implications of Bolsonaros victory are potentially as far-reaching as the Trump presidency. Like his US counterpart, Bolsonaro is a climate-change denier. During his campaign, he initially said he would take the country out of the Paris Climate Change Agreement, although he later moderated that position. Nonetheless, following the elections in Brazil, illegal forest clearance in the Amazon has jumped by 50 per cent, as developers are convinced that Bolsonaro will support their plans to expand agricultural land and mining sites at the expense of the worlds most important natural habitat. If, as is feared, this pattern continues during his presidency, it will be the single biggest setback to the measures put in place by the Paris Agreement to combat climate change.

Yet despite this, Bolsonaro takes office boasting huge domestic popularity. He won the election in the second round with 55 per cent of the vote and, as he prepared to take power, 75 per cent of Brazilians said he was on the right track, with only 15 per cent condemning his extremist policies. The Mechanism offers key insights into how and why this happened.

Bolsonaros election victory came as Brazil was recovering from what, by some estimates, was the largest corruption scandal in history anywhere in the world. In Brazil it is known by the name of Lava Jato or Car Wash. The name comes from a somewhat convoluted reference to a petrol station, which provided the information leading to the first arrests in this scandal. At the time, the detectives and prosecutors involved had no idea that this routine investigation would be lifting the lid on a nation wide cesspit of money laundering and corruption which went right to the very top of Brazilian politics and business. Not only did it engulf the countrys superstar politician, former president Luiz Igncio Lula da Silva, known simply as Lula, it also culled some of Brazils most powerful oligarchs, notably Marcelo Odebrecht, the erstwhile CEO of South Americas largest construction company, Odebrecht. The reverberations were felt not only across Brazil but also much of South America where, it emerged, Odebrecht had been bribing politicians and civil servants left, right and centre.

It is impossible to understand the rise to power of Bolsonaro without pulling back the curtain to reveal the mind-boggling scale of Car Wash. Until the scandal, this former army captain was widely regarded as a ludicrous, isolated figure in the Chamber of Deputies spouting fanatical rhetoric. But much like Trump in America, he recognised the disgust many Brazilians felt regarding mainstream politics, and his assault on power was supercharged by the fallout from Car Wash.

Next page