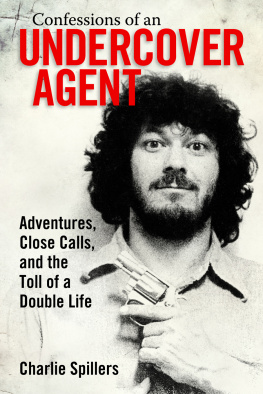

John Shobbrook was born in Brisbane in 1948. He joined the law-enforcement wing of the Department of Customs and Excise in Brisbane in 1969, and in 1972 he was promoted into the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, where he eventually became second-in-command of the Northern Region of the Narcotics Bureau encompassing Queensland and the Northern Territory. His final investigation for the Federal Bureau of Narcotics was Operation Jungle, which brought him to the attention of the Australian Royal Commission of Inquiry into Drugs. The evidence that he provided to that commission led to his dismissal from the Australian Federal Police.

John Shobbrook was born in Brisbane in 1948. He joined the law-enforcement wing of the Department of Customs and Excise in Brisbane in 1969, and in 1972 he was promoted into the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, where he eventually became second-in-command of the Northern Region of the Narcotics Bureau encompassing Queensland and the Northern Territory. His final investigation for the Federal Bureau of Narcotics was Operation Jungle, which brought him to the attention of the Australian Royal Commission of Inquiry into Drugs. The evidence that he provided to that commission led to his dismissal from the Australian Federal Police.

In 1994 John moved to Coonabarabran in north-western New South Wales to commence a career in astronomy, which included working for two years as a Planetarium Director in California. He and his wife returned to live in Brisbane in 2013.

For Harvey Bates

and the dedicated officers of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics who suffered at the hands of corrupt absolute power.

Contents

Introduction

by Matthew Condon

Just months after Douglas John Shobbrook was born and quickly adopted out into the world in the late autumn of 1948, the pieces of a great and corrupt machine were quietly moving into place.

At the brown-brick police depot on Petrie Terrace, in Brisbanes inner west, a young man named Terence Murray Lewis started his nine-week training course to become a Queensland police officer. Lewis, then twenty, lived at the police barracks for the duration of the course, and bragged to fellow trainees about his hopes of being posted to a country town as soon as possible, where he could cop a sling-back from SP bookmakers.

Down at the Criminal Investigation Branch (CIB), in an old former church building at the corner of Elizabeth and George streets, Sub-Inspector Frank Bischof, known as The Big Fella, had established himself as the states leading detective, with an almost-perfect murder resolution sheet. Bischof had steadily risen through the ranks despite his penchant for shortcuts and fabricating evidence. He was a chronic gambler and excessive drinker, and he had a keen eye for illicit cash.

Bischof had learnt a lot during World War II about graft, protection kick-backs and how to get away with police corruption when thousands of American troops were stationed in his city to defend the so-called Brisbane Line and American General Douglas MacArthur had his headquarters in Edward Street. Bischof, however, had become enmeshed in the citys sly grog rackets, illegal gambling dens and lucrative prostitution parlours. He would take those skills, learnt in times of an enforced black market, into the future.

Also at the CIB in the late 1940s was a young detective named Tony Murphy, who was a rapidly ascending star in the force at the time Shobbrook was taken in by his adoptive parents, Alfred and Sarah Shobbrook, and settled in Anglesey Street in Kangaroo Point.

Before Shobbrook turned one, another officer completed his training at the Queensland police barracks: Jack The Bagman Herbert. Herbert would later help mastermind a corrupt system within the police force known as The Joke. Begun as a means of securing ready cash through bribe money, The Joke would creep like a virus through almost every part of Queensland life.

Shortly after Herbert began his calisthenics and legal exams at the Petrie barracks, while young Shobbrook was not yet old enough to attend primary school, the final piece in the puzzle was installed. Glendon Patrick Hallahan, a former cane-cutter and Royal Australian Air Force aircraft apprentice, joined the force. He could have been a son to Bischof; both men were born in Toowoomba, and they shared a taste for fancy clothes and for the retrospective invention of evidence to suit a crime.

The insidious machine, with its cabal of compliant, corrupt officers, was beginning to hum.

Shobbrook was ten years old a child enjoying the spectacle of the annual Royal Exhibition, or Ekka, with its strawberry-topped ice creams and showbags when Bischof was elevated to the police commissionership, and his boys, as he called them Lewis, Murphy and Hallahan became his fully fledged partners in crime. The trio became known as the Rat Pack.

As Shobbrook was being thrilled by the wood-chopping events and Sideshow Alley, Lewis was on duty patrolling the Bowen Hills show site. They may have passed each other in the crowd. At the same time, local prostitute Shirley Brifman was earning a quid off the travelling carneys show time was always a busy week and a half for the working girls of the city. Brifman would become close to both Murphy and Hallahan, and pay money to them for protection. She would also play an instrumental role as a police informant, keeping Bischof and the Rat Pack in touch with local crime and underworld machinations interstate.

Bischof relished his position of power as commissioner, and over time refined The Joke to perfection. The tank stream beneath his longevity as commissioner was the salacious information he collected on his political masters and others in positions of authority. It served him well.

In the early 1960s, fourteen-year-old Shobbrook left school and took up a number of jobs, including assembling household taps, labouring on a dairy farm, and working as a storeman for a company that sold car cables, as well as another that manufactured office storage furniture. On 29 October 1963, as Shobbrook was cycling to the Brownbuilt factory in Salisbury, about 13 kilometres south of his parents home, the state member for South Brisbane, Col Bennett, triggered mayhem when he stood up in parliament and issued a damning indictment of the Queensland police.

On that famous day, Bennett said, I believe we have a large body of men in the Queensland Police Force in whom we can have only the greatest of pride; but I further believe that those men, in the carrying out of their tasks, are being frustrated, disconcerted and disillusioned, first of all, through the lack of attention by the Government and the Cabinet, and secondly, by the example that is set for them by the top echelon of the Police Force.

Bennetts aim was to expose Bischof and his Rat Pack. Late in his hour-long speech, he lit the fuse to a powder keg. I do not wish to dally too long on this subject, he said, but I should say that the Commissioner and his colleagues who frequent the National Hotel, encouraging and condoning the call-girl service that operates there, would be better occupied in preventing such activities rather than tolerating them.

The National Hotel was a notorious watering hole at Petrie Bight, run by the Roberts brothers: Max, Rolly and Jack. The brothers were friends of Bischof and his Rat Packers, and Shirley Brifman and her fellow prostitutes often worked out of the National. Bischof denied this, although it was said that even Brisbane schoolchildren knew that the National was a proxy brothel.

Soon after Bennetts revelations, Premier Frank Nicklin announced a royal commission to investigate police misconduct the first of its kind held in Queensland with Justice Harry Gibbs as the royal commissioner. However, the inquirys terms of reference were so narrow that there was little possibility that Bischofs corruption would be even remotely exposed. Additionally, Bischof sent out his crack team Murphy and Hallahan to harass and threaten potential witnesses. Brifman was coached by them prior to her appearance at the royal commission and repeatedly perjured herself.

John Shobbrook was born in Brisbane in 1948. He joined the law-enforcement wing of the Department of Customs and Excise in Brisbane in 1969, and in 1972 he was promoted into the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, where he eventually became second-in-command of the Northern Region of the Narcotics Bureau encompassing Queensland and the Northern Territory. His final investigation for the Federal Bureau of Narcotics was Operation Jungle, which brought him to the attention of the Australian Royal Commission of Inquiry into Drugs. The evidence that he provided to that commission led to his dismissal from the Australian Federal Police.

John Shobbrook was born in Brisbane in 1948. He joined the law-enforcement wing of the Department of Customs and Excise in Brisbane in 1969, and in 1972 he was promoted into the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, where he eventually became second-in-command of the Northern Region of the Narcotics Bureau encompassing Queensland and the Northern Territory. His final investigation for the Federal Bureau of Narcotics was Operation Jungle, which brought him to the attention of the Australian Royal Commission of Inquiry into Drugs. The evidence that he provided to that commission led to his dismissal from the Australian Federal Police.

.png)