The quest of the truth had been born in methe most tragic and incomplete, as well as the most essential, of mans quests.

Ida Tarbell, All in the Days Work

In America the President reigns for four years, and journalism governs forever and ever.

Oscar Wilde, The Soul of Man Under Socialism

Contents

I n the Gilded Age, when the magazine was readying its ascent, cities sounded more like barnyards of the past than metropolises of the future. Hoofbeats punctuated the long avenues of New York, and the light step of a messenger boy was more frequently heard than the ringing of a telephone. But it was nevertheless a time shaped by the advent of the machine: the whirr of cable cars, the colonizing force of the railroad, the miracle of wireless telegraphy, even the boisterous new leisure activity made possible by the bicycle. Every facet of life was affected by a new reliance on mechanization and speedy communication that hadnt existed a generation before, opening new channels for the accumulation of money and social control. How could anyone hope to understand this as it was happening? Preachers and politicians did their best, but most people turned to the press.

A magazine seems to be a frivolous thing: a way to pass the time in a waiting room or on a commute, a way to take a break from the work of real thinking. But behind each pulp-and-ink issue lies a gargantuan effort to satisfy the curiosities of an anxious society. Each article represents a claim on the readers attention, as well as a period of obsession, or at least dutiful fixation, for the writer behind it. In the years before radio, television, and the internet, this meant readers from all walks of lifefrom the president to the newly literateturned to the written word to tell them what exactly they were living through, and what might come next.

The Gilded Age takes its name from an 1873 novel by Mark Twain and journalist Charles Dudley Warner. The two friends, provoked by a dare from their wives, collaborated on a story that satirized what they saw as a mindless, materialistic America around them. But it could have had a third allusion, to a sensational yet significant age of journalismand of magazines, as a form. Out of a heated, competition-driven surge in print media, the now-vanished McClures magazine rose up and leveled reportage and entertainment at a growing American readership, coming to embody the emerging art of investigative journalism.

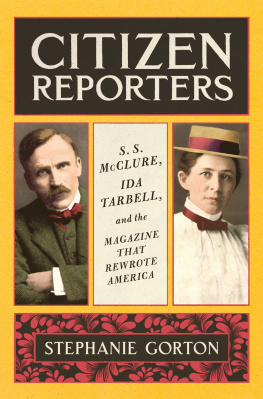

With origins in immigrant-packed steerage quarters and the rapidly industrializing Midwest, the strivers who made McClures brought long-held quests and biases to the task. Theythe visionary Samuel Sidney McClure, dauntless Ida Tarbell, dedicated John Phillips, gentle Ray Stannard Baker, idealistic Lincoln Steffens, and dozens of other reporters and novelists in their circlechanneled their vision into print, creating a magazine whose roving interests paralleled the evolving concerns of the society around them. Their lives and loves, as well as their work, were consumed by the magazines success and dissolution.

In the last years of the nineteenth century and the first decade of the twentieth, the frontier vanished, Victorian values were pushed aside, and entrenched political corruption sparked a grassroots reform movement. Railroads extended their reach across the continent, requiring American time zones to be standardized for the first time; town clocks no longer set their time by the sun or the local almanac, but by the railroad schedule. Electricity lit cities that had previously been dim and smoky with kerosene and whale oil, and telegraphy accelerated the end of the Pony Express. A dentist from Buffalo invented the electric chair, which dispatched its first murderer in early August of 1890. Life was brighter and more efficient, but also fraught with new ways to die.

Throughout the Gilded Ageand its hopeful successor, the Progressive Erathe United States was deeply divided between progressives and conservatives, stretched by recessions at home and wars abroad, and astonished by advances in speedy new communications technologies. Wealth inequality had never been higher. At the same time, gender roles were being renegotiated, and race relations seemed to have reached a postslavery crisis point. All this meant there was a demand for stories that could make sense of the brave new world and no shortage of material for socially conscious writers. A revelatory story or investigation could rock a political administration, bring together a reform campaign, and powerfully articulate tensions simmering in the surrounding culture. In 1892, in the words of reformer and lawyer Clarence Darrow, there was a declared shift in public taste from the romance of fairies and angels to instead flesh and blood.

The written word never held as much power as during this period of transformations. Actors might have been known by name across the country, and traveling lecturers appeared in towns large and small, but many lacked the means or the time to attend plays and talks. Print was the only mass medium, and the pulpit, the press, and the novel influenced an increasingly literate population. In the postCivil War years, the prevalence of magazines in America mushroomed. In 1860, there were about 575. That number practically doubled every decade until, by 1895, there were more than 5,000. Reporters words did not only fill space on the page; they could make or break campaigns, careers, products, and fashions.

The rise of magazine journalism drew attention, attempts at shaping the narrative, and deepening dismay from those in elected office. It is always a pleasure to a man in public life to meet the real governing classes, Roosevelt began a speech on April 7, 1904, in the ballroom of Washingtons New Willard Hotel. He was speaking to the inaugural industry banquet of the Periodical Publishers Association, including several members of the McClures group. The rest of his speech focused on the theme of restraint. He urged his listeners to realize their own political influence and wield it with care. The man who writes, the president told the crowd, the man who month in and month out, week in and week out, day in and day out, furnishes the material which is to do its part in shaping the thoughts of our people is fundamentally the man who, more than any other, determines what kind of character, and therefore ultimately what kind of government, this people shall possess.

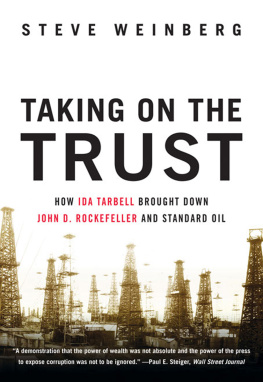

Out of all the loud-shouting newspapers and venerable magazines of the day, McClures was unprecedented in its determination to entertain, to chase the allure of the new, and to expose injustice. McClures stories agitated for change, though they also sought subscribers the way television producers now chase ratings. They exposed the dysfunction of mob-run cities like St. Louis and Pittsburgh and destabilized the monopoly on industry held by oligarchical tycoons, particularly John D. Rockefeller.

S. S. McClures conviction that a magazine could be a cultural force kept McClures sharply attuned to the demands of the reading public. The magazine embodied the muckraking genre; this term for investigative journalism was arguably invented for McClures. By 1900, McClure was widely recognized as one of the most important men in America. In a later reflection in Life, the writer noted, nobodys hand has been more perceptible than his on the crank that turns the world upside down. At its peak, McClures had more than 400,000 subscribers, soundly beating its rivals Harpers Monthly, Scribners Magazine, The Century, and The Atlantic.

S. S. McClure himself was a queer bird, but a lovable man and a great one... stranger than any fiction, in the words of one reporter who knew him. He was a perceptive editor and larger-than-life man, described by his friend Rudyard Kipling as a cyclone in a frock-coat and likened to both Theodore Roosevelt and Napoleon. Today he might be seen as part Citizen Kane, part Wizard of Oz: a blazing talent with outsize self-belief and what might today be diagnosed as manic depression or bipolar disorder. He discovered and mentored obscure young journalistsincluding Ida Tarbell, Ray Stannard Baker, Lincoln Steffens, and Willa Catherwho became the most brilliant staff ever gathered by a New York periodical, according to contemporaneous