CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- STANDING STONES, RUNES AND PAGAN ALTARS

- LEGENDARY SKULLS, STRANGE REMAINS AND WEIRD REPOSITORIES

- GIANTS GRAVES, ODD EPITAPHS AND RESURRECTION MEN

- MYSTERIOUS CRYPTS, SECRET TUNNELS AND MACABRE EFFIGIES

- HOLY WELLS, SACRED EELS AND SAINTS SKULLS

- ODD ARTEFACTS AND STRANGE CEREMONIES

- AN EMPORIUM OF ODDITIES

- FURTHER READING

- PLACES TO VISIT

INTRODUCTION

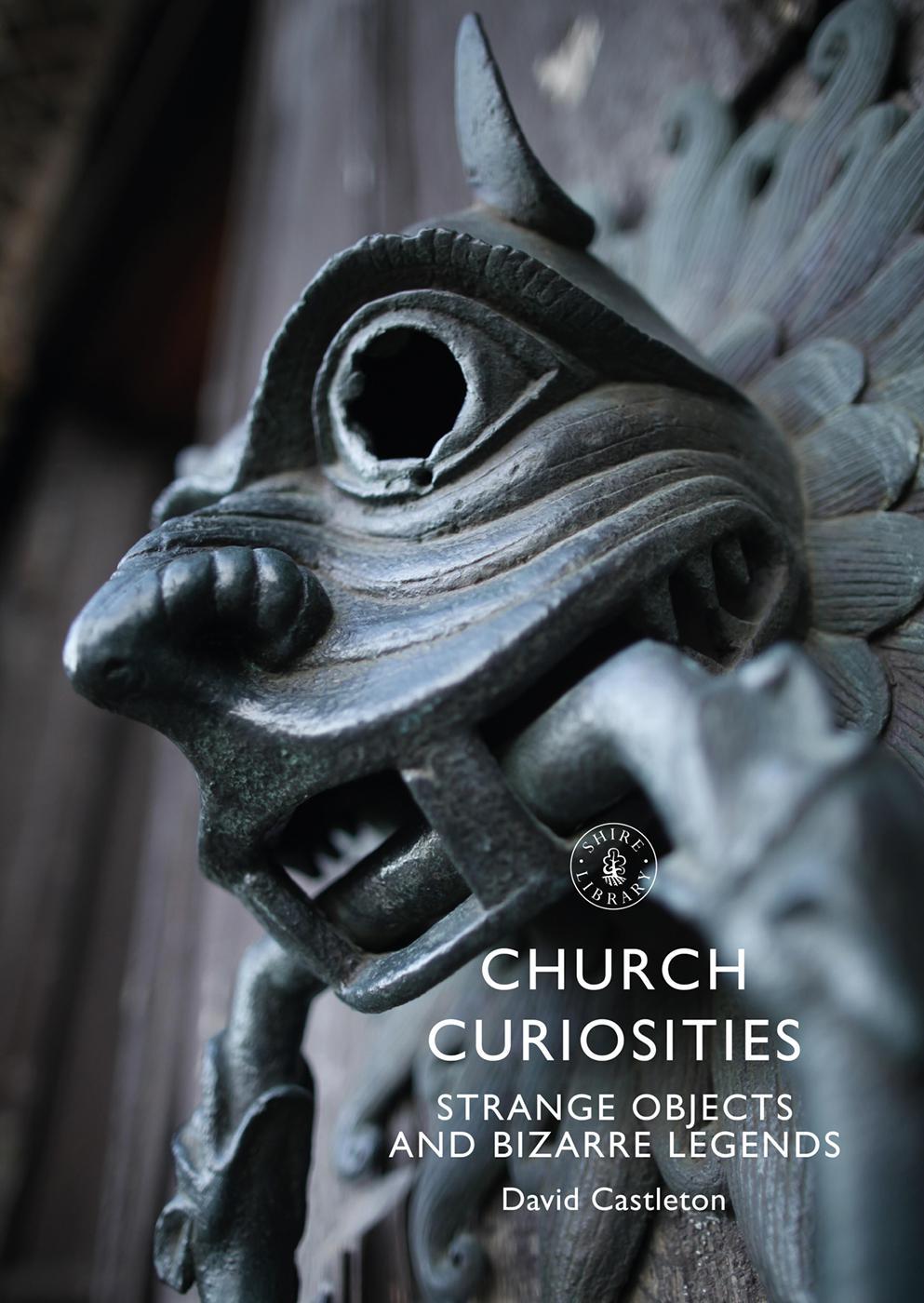

B RITAINS CHURCHES SEEM such familiar features of its countryside and cityscapes that many of us dont realise how bizarre these buildings can be. The dark steeples standing reliably against the sky, the unremarked arched windows, the leaning weathered gravestones all these can appear so commonplace that most people are largely unaware that British churches house artefacts linked to the most incredible legends, the strangest stories, the most mindboggling pie ces of history.

British churches and cathedrals host objects as odd as saints skulls converted into drinking cups, dragon-slaying swords and spears, the mummified heads of famous statesmen, crowns and garlands that once bedecked virgins coffins, and millennium-old shamanic reindeer horns.

Stroll out into the churchyard and it gets even weirder. Here we find legends of dead men seated in pyramids, with bottles of port ready to open on Judgement Day. British churchyards contain devils footprints, evidence of attempts to outwit body snatchers, enormous standing stones, the graves of vampires and giants, the tombs of characters from Britains bountiful literary history, and rocks that will inform us when the Apocalypse is approaching.

From imps petrified by angels to eggs painted with clowns make-up, from stocks and ducking stools to the embalmed hearts of ghostly monks, from preserved robins nests to the graves of beloved dogs and cats, from door knockers modelled on demons faces to holy wells whose waters fizz on sacred days of the year, these oddities really do make Britains cathedrals and churches repositories of the bizarre.

This book is a brief introduction to such curiosities and to the tales, legends and folkloric ceremonies associated with them. We begin our journey by examining items mysterious menhirs, stones etched with runes, goddess sculptures, carvings from Norse myth that are remnants of a pagan, or possibly pagan, past. Our voyage through the strange continues with a look at ancient relics mummified apostles hands, preserved archbishops skulls, the ribs of monstrous cows after which we step out to explore the churchyard. The enigma of what lies beneath British churches comes next bone crypts, shadowy undercrofts, spooky effigies, secret tunnels before we gaze into the wonderful history of holy wells. We then investigate the folkloric pageants and rituals that are, or once were, centred on churches from boys masquerading as bishops to children listening for witches frying pancakes under hills and finish off with a round-up of random oddities, ranging from French cannonballs embedded in towers to burn marks left by bl ack hellhounds.

During my work as a fiction writer whose output draws heavily on the legends and peculiarities of the British landscape and as a blogger focused on the dark, strange and quirky, Ive been constantly surprised by just how weird so much of my countrys heritage is. And much of that eccentric inheritance is found within churches a nd churchyards.

Its my hope that, after reading this book, you will never again look on churches as dull or merely functional buildings, but rather see them as stores of myth, history and legend, and as treasuries of charming, disturbing, precious and deeply unu sual artefacts.

La GrnMre , who stands at the gate of St Martins Churchyard, Guernsey, was probably first carved in Neolithic times, possibly from a standing stone. Flowers are often placed at the statues feet and coins left on her head. She is a popular addition to wedding photos!

STANDING STONES, RUNES AND PAGAN ALTARS

I T MIGHT SEEM odd to talk about pre-Christian or pagan survivals in churches. Surely a religion dedicated to the one true God would have made sure its houses of worship were cleansed of heathen objects and all traces of competing deities? It also might seem obvious that any dubious artefacts wouldnt have survived long centuries of Christian dominance and especially the efforts of zealous Protestants to root out superstition during t he Reformation.

Though this is generally the case, there are here and there oddities in British churches that date from or at least may be folkloric echoes of the pagan past. The conversion to Christianity was a piecemeal and gradual process, frequently interrupted by pagan resurgences. Though begun under the Roman Empire, the conversion of the Romanised Celts was not complete when the Romans left and invasions by other pagan peoples Saxons, Angles, Jutes and later Vikings coloured the fabric of British life. At certain times, paganism and Christianity coexisted and there are records of the same building being used for both forms of worship. Churches were sometimes built on pagan sites, presumably both to suppress the old religion and to benefit from the reverence locals had for such places. Plundered objects from temples were reused in the construction of churches. Vestiges of paganism may have lingered in the popular mind long after the official conversion. Medieval Arthurian legends mingled Christian and pagan themes while superstitions against damaging barrows and standing stones lasted into the 1800s. It could be argued this continuity between the two faiths is reflected in some strange artefacts in British churches a nd churchyards.

Its sometimes hard, however, to disentangle whats pagan from whats Christian. Is the graphic female image of the Sheela-na-gig, for instance, a medieval remnant of pagan fertility beliefs or a stern Christian warning against lust? Ancient Nordic runes can convey Christian piety while stone crosses might be engraved with the adventures of Norse gods. There are also more utilitarian considerations were churches, for instance, built within ancient earthworks because of the populaces attachment to these mystical sites or because of prosaic motives like defence and access to water sources? We should remember too that some researchers especially our enthusiastic Victorian forebears have sometimes committed the error of supposing mysterious artefacts and peculiar folkloric customs automatically spring from a romantici sed pagan past.

This chapter doesnt claim every oddity it mentions is definitively pagan, but merely aims to highlight objects in British churches that at least seem questionably Christian or that may harbour some resonance from heathen times.

A striking juxtaposition of the Christian and pagan can be seen at Midmar Church, Aberdeenshire, where a Bronze Age stone circle stands in the churchyard. Estimated to be 4,000 years old, the circle is 17 metres in diameter, with some of the stones reaching 2.5 metres in height. The standing stones, which mingle strangely with the later Christian grave markers, form one of north-east Scotlands best-preserved recumbent stone circles, recumbent meaning that some stones were set up lying down. The Midmar area seems to have been a site of ancient religious importance, as two other stone circles lie to the east and south-east of the village and standing stones are scattered throughou t the locality.