Publication of this volume was made possible in part

by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Copyright 2000 by The University Press of Kentucky

Paperback edition 2009

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 405084008

www.kentuckypress.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the hardcover edition as follows:

Mathias, Frank Furlong.

The GI generation : a memoir / Frank F. Mathias

p.cm.

ISBN 0-8131-2157-4 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Mathias, Frank Furlong.2. United StatesSocial life and

customs20th century.3. Depressions1929Kentucky

Carlisle.4. World War, 19391945Personal narratives, American.

5. Carlisle (Ky.)Biography.I. Title: G.I. generation.II. Title.

CT275.M46444 A3 2000

973.91dc2199-089854

ISBN-13: 978-0-8131-9321-2 (pbk.: alk. paper)

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper

meeting the requirements of the American National Standard

for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Member of the Association of

American University Presses

Preface

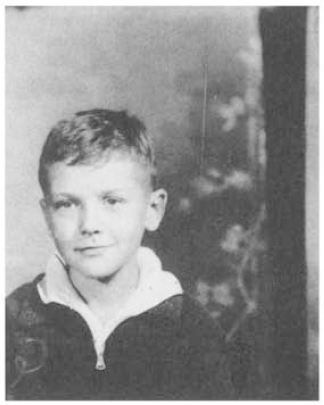

On August 25, 1943, I entered the United States Army as an entirely willing eighteen-year-old draftee. I joined several million other lads born between 1910 and 1927, a spread of years catching most of Americas World War II servicemen. As if to balance the biblical passage A time to be born, these years embraced a time it might have been better to have postponed ones arrival, for we were the star-crossed GI Generation destined to help pull the worlds bloodstained chestnuts out of the fires of fascism, then for the rest of the century devise a safe yet perilous path through the threat of nuclear war. We did these things, I think, because they had to be done, and it was up to us to do them. Exactly the same can be said for those lads who fought the Revolution, the Civil War, and World War I.

It can also be said that the decades preceding a war witness the sprouting, growing, shaping, and maturing of the men called to fight the war. And that is the major theme of this book. Although I reveal the thread of only one boys life, along with that of his small community, it is woven thoroughly throughout the fabric of his entire generation, for the Great Depression notwithstanding, the two decades between the wars were years of national and social and cultural unity. We could not have won without it. Once in the army I found that my diverse comrades and I shared most of the same beliefs, tastes and distastes, education, music, humor, fears, and much else. Although much has been written about the GI Generation after they entered combat, practically nothing has appeared tracing the ins and outs of their lives as they grew to maturity between the two greatest wars of all time. This book proposes to show my life and through it the similar lives of that much greater entity now known as the GI Generation.

Readers younger than I may be surprised to find that life between World Wars I and II did not embrace expanded versions of the America one finds in the novels of F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Steinbeck, and Sinclair Lewis. Writers too often have overplayed the jazzy, jobless, or smugly conventional sides of life lived by some Americans during two of the most crucial yet interesting decades of the turbulent twentieth century. Most of us lived lives far removed from those of the Gatsbys, Joads, or Babbits. Like Einsteins realization that a falling man feels no force of gravity, we whose youth fell within these disordered decades lived reasonably happy lives, with little or no sense of the ever-mounting gravity of each prewar year. Who was I to know that ten of my playmates or pals would be killed in action just a few years down the road? We were chock-full of the optimism of youth and thoughtless of any future much beyond high school graduation. Moreover (although we were part of it), the phrase GI Generation would have been as meaningless to us as ball point pen or tape recorder. In short, I intend to paint a much happier, more humorous, and truer face on these twenty-odd years between the wars. I shall also let the reader link the war to my pals and me by mentioning future battle deaths of playmates and pertinent or related experiences of my own during the war.

It may be hard for todays reader to grasp how quickly postarmistice World War I began converting itself into World War II. By the time of my birth, in 1925, World War II was, for all practical purposes, already in its planning stages. Germany and Russia were secretly violating postwar treaties to promote each others military power. In return for Krupp know-how in building a Russian munitions industry Moscow set aside vast tracts of land for German training of young fighter pilots and for the testing of new tank formations as well as heavy artillery. William Manchester revealed this and similar shenanigans in his 1964 book The Arms of Krupp. Additionally, the ill-starred year of 1925 witnessed not only the withdrawal of French troops from the Ruhr but Adolph Hitlers publication of Mein Kampf, as he set about building a powerful Nazi Party. Mussolini, of course, had taken over and run fascist Italy for three years by this time. But as will be seen in the opening chapter, I was born into a Jazz Age Kentucky bungalow with nary a worry in the world. My parents, like nearly all Americans, believed World War I, the war to end all wars, had made the world safe for democracy. We lived, loved, and operated on that belief until the seventh day of December 1941. Thats the day the entire GI Generation came of age!

There is no better example of what is meant by coming of age than that of my cousin Bob Mathias, the son of Uncle Harry and Aunt Catherine Marshall Mathias. Stephen E. Ambrose, in the prologue of his splendid book D-Day, June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II ([New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994], 2226) offers the wartime action of Bob and another young man as examples of what Hitler was up against in his overconfident belief that democracies produces weaklings:

Lt. Robert Mason Mathias was the leader of the second platoon, E company, 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment, U.S. 82nd Airborne Division. At midnight, June 5/6, 1944, he was riding in a C-47 Dakota over the English Channel, headed toward the Cotentin Peninsula of Normandy.... The Germans below were firing furiously at the air armada of 822 C-47s.... Mathias had his hands on the outside of the doorway, ready [to lead his sixteen men out] when a shell burst beside him.... knocking him off his feet. With a mighty effort he pulled himself back up. The green light went on.... The crew of the C-47 could have applied first aid.... Instead, Mathias raised his right arm, called out Follow me! and leaped into the night... bleeding from his multiple wounds.... When he was located a half hour or so later, he was still in his chute, dead. He was the first American officer killed by German fire on D-day.

Member of the Association of

Member of the Association of