BALKAN VILLAGE

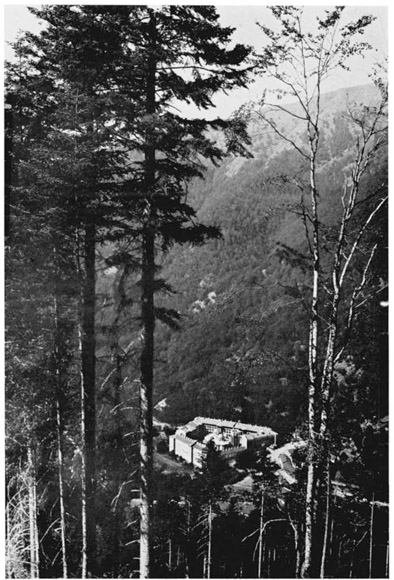

Rila Monastery, sacred to Bulgarians for six centuries

BALKAN VILLAGE

by

IRWIN T. SANDERS

With Original Photographs by the Author

Lexington: 1949

COPYRIGHT 1949

IRWIN T. SANDERS

Dedicated

to

My Mother

FOREWORD

THE EUROPE of headlines and newsreels and newscasts is a Europe we Americans know all too well. It is the Europe of swiftly maneuvering armies, umbrellas of planes, and scorched earth. Its air is filled with noisy propaganda, whispered intrigue, and the cries of starving children. This was the Europe of tottering dictators and victims restive for the day of liberation.

There is another Europe whose foundations are laid far in the past of people working a well-loved land, of peaceful rivers carrying barges laden with fruit and grain, of families of storks returning from Egypt, as they have for a thousand years, to nest in the same protected spots. This is the Europe I have known and loved as I saw it from a tranquil village clinging to a Bulgarian mountainside, in the shadow of a twelfth century monastery.

No one village can typify a whole region, yet the faithful account of the everyday life of this Balkan village through the 1930s does reveal something deeper than the picturesque or the spectacular. It reveals the timbers out of which generations of rural Europeans have constructed their lives. And it reveals further the stability, the weakness and strength of a rural community where change comes not so much through violence as through the slow, inevitable processes of time. The prewar Europe of Baba Draganas children, living out their patiently laborious days in the rhythm the seasons set for them, was to me the Europe that seemed permanent.

Yet in the Balkans today an irresistible force is meeting an immovable objectand both are being changed by the impact. Communism, with its dynamic drive for power, its sense of mission, and impatience for reform, is charging against the Balkan peasant mass, a mass which heretofore has preferred tradition to science and familiar ways of the past to what we moderns choose to call efficient living.

Dragalevtsy, the village described herein, brings this struggle into focus. It reveals the nature of that Balkan peasant mass wherever it is based on private ownership of home and fields; the travail of this village since the war reveals something of the kinds of forces now at work.

My sympathies go not to the extremists of either sidenot to the revolutionaries of the moment nor to the devotees of the pastbut rather to the millions of men and women and even little children who are caught, trapped, wedged in by the impact; people whose one desire is the opportunity to earn their daily bread, the chance to laugh and love and to close their eyes at night without dreading the thought of waking on the morrow.

IRWIN T. SANDERS

December, 1948

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

THIS BOOK has really been In process since 1929, the date of my first contact with the Bulgarian peasant and his interesting manner of life. Since that time many people have helped me gain the background out of which this book has grown. The people of Dragalevtsy themselves deserve a special tribute for their patience and co-operation; some of the government officials in Sofia provided basic statistical data; while my colleagues at the American College of Sofia aided me greatly in understanding the rural folk of Bulgaria. Dr. Floyd H. Black, President of the College, did much to facilitate my research and trips of investigation, and Dr. Heinrich Schneider, now of Cornell University, aided me in a search for German source materials. The late Professor Dwight Sanderson, of Cornell University, guided me through much of my research, even to the point of visiting me in Bulgaria. Dr. C. E. Black of Princeton University, Professor C. Arnold Anderson of the University of Kentucky, Mr. Clayton E. Whipple of the Office of Foreign Agricultural Relations, Washington, and Dr. William Kling of the United States State Department have made many valuable suggestions. But I am more deeply indebted to my wife than to anyone else, especially for her constant interest in this task and her competent help.

The editors of the Journal of Applied Anthropology, Rural Sociology, Sociometry, and Social Forces have kindly permitted me to reprint material originally appearing in their publications.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Rila Monastery, sacred to Bulgarians for six centuries

MAPS AND TABLES

APPENDIX TABLES

BALKAN VILLAGE

CHAPTER I

THE PEOPLE AND THEIR VILLAGE

WINTER had begun. The first snow of the year had fallen. It covered the muddy streets of the village, softening the nakedness of the fruit trees which stood lonely in the bare yards. The wind from Mount Vitosha came whistling down the empty lanes, sending both man and beast to seek protection and warmth. The animals huddled in their thatched folds and shelters; the women and children crowded on the little stools near the fireplace at home. The fall sowing of wheat was in. The fields, wind-swept and snow-laden, were deserted, seemingly forgotten by the men and women who had spent so much time with them during the past months.

One ordinary day followed another. Every morning the water buffalo had to be groomed until they shone; the oxen had to be cleaned after the night in the dirty stall; these, as well as the sheep, had to be fed. Usually the animals received their meager rations before ten oclock. Shortly thereafter the men, wearing their dirty-gray sheepskin coats, their brimless lambskin hats, and their pigskin sandals, congregated at the taverns to relieve the monotony of their daily routine. At noon they plodded home to a lunch of beans, looked after the cattle once more, and gave commands to their womenfolk. The rest of the day was spent at the taverns in drinking and talking, interspersed with long, easy silences. After the evening meal, the cattle were fed again. Then the men dropped off to sleep along with the rest of the household.

The winds and enforced idleness of winter were not alone responsible for the apparent sluggishness on every hand. Slow motion was characteristic of Dragalevtsy life in general, but especially of the bodily movements of the people. Ima vreme (theres plenty of time) was either a practical philosophical tenet which explained their lack of hurry or else it was an expression frequently used to rationalize their casual manner. I never saw a peasant with a watch.

These quiet people of Dragalevtsy, whose way of life is not very different from that of peasants throughout the Balkans, are more than just Bulgarian peasants who arose in the seventh century from a dash of Tartar added to a predominantly Slavic mixture. They are a special breed of Bulgarians called Shopi, a term originally meaning boorish. That is, a Shop was a bumpkin. Some authorities say that this term was derived from sop, the long staff which the men of this area carried. Since those living in the Shopsko area, or the immediate vicinity of Sofia and Mount Vitosha, are in general more conservative than villagers elsewhere in Bulgaria, the word Shopi also carried the idea of backwardness and mental simplicity. Among the many attempts to explain the special physical characteristics of these people, the most plausible theory is that of descent from the Pechenegi, or Mongolian tribesmen who infiltrated into that section of Bulgaria and nearby eastern Serbia in the eleventh century. Historians deal none too kindly with these Pechenegi; nor do the